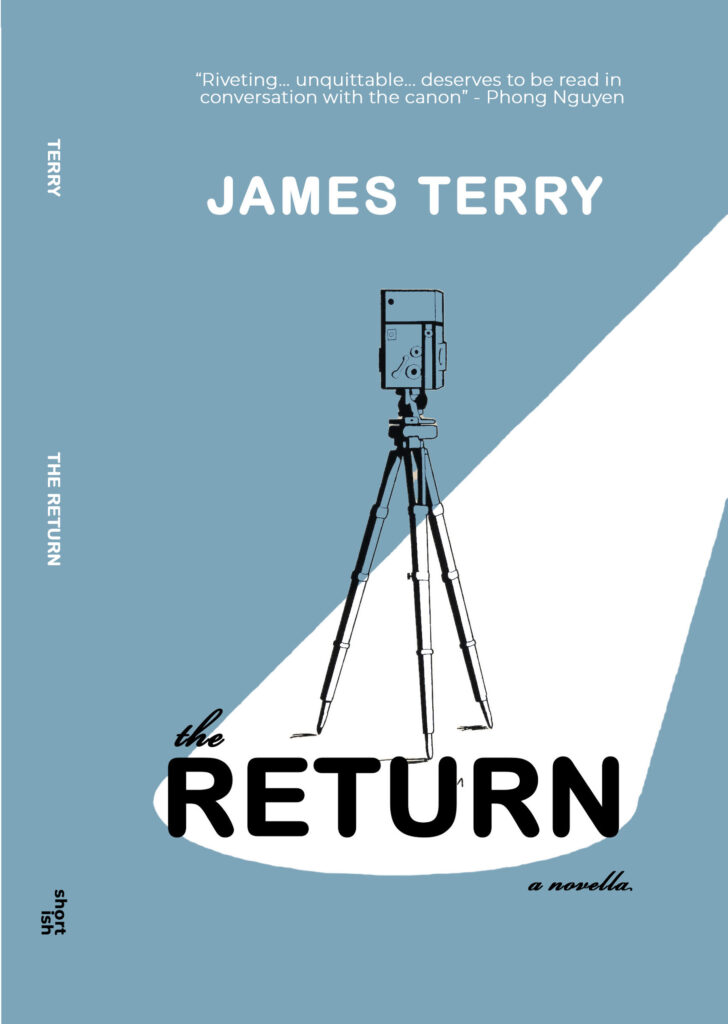

Writer James Terry, ’92, loved Berkeley and the culture that surrounded it—all the funky moviehouses, legendary bookstores, and iconic cafes, most of which have disappeared with the times. The author of several novels and short story collections, Terry has wanted to write about his alma mater for a long time. In his forthcoming novella, The Return, Terry revisits UC Berkeley through the eyes of protagonist Bernard Aoust, a film professor nearing retirement who finds himself increasingly at odds with modern life. A Frenchman by birth, and an ideological child of the youth uprisings of May ’68 France, Aoust is obsessed with a long-lost silent French film from 1923 and its obscure director, devoting his academic life to the film and banking on a new monograph to salvage his flagging career. The book explores what we lose when long-established art forms and means of communication—like watching movies together in a cinema—die out and are replaced by new ones.

The Return will be published by Outpost19 in September. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

UC Berkeley plays a salient role in your novella The Return, which follows Professor Aoust, an aging film scholar anxious about his obsolescence among newer generations of students in a rapidly changing technological environment. Why did you choose this setting?

I really had to set the story at UC Berkeley because I wanted to draw on the wealth of my personal experiences from my time as a student there, back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, though the story is set much later.

What about Berkeley inspired the novella’s themes of loss, change, and personal and professional crisis?

Berkeley, and the university, have a unique and unmistakable vibe, partly owing to the history of student protest, the ethos of Northern California, and its reputation for left-wing politics. Professor Aoust is a child of May ’68 Paris, so he fits right in at Berkeley, or at least he used to. But the world has changed, as has Berkeley. So, yes, I wanted him to embody some of my own nostalgia, and I wanted him to suffer a fall for it, for not being able to change with the times.

Speaking of changing with the times, your protagonist has a hard time adapting to the new classroom, with social media, AI, and the omnipresent distraction of the cell phone. Should we see a kind of resistance to this trend in Aoust’s persistent cinema obsession—silent cinema especially—and his aversion to noise in favor of productive silence?

The epigraph to The Return is “Freedom is the right to silence,” which was spray-painted on a wall at the Sorbonne during the student protests of May ’68. I like the irony that you hear a version of this when you’re being arrested. Silence is a big theme of the book. Not just Aoust’s passion for silent cinema, and his own aversion to music/noise, but the metaphorical silence that is the right to solitude and the right to one’s own dreams and memories. Silence as white space in one’s life.

Aoust isn’t so much resisting a trend as constitutionally incapable of seeing any value in these technologies. I’m not in a university environment myself, so it’s hard for me to judge what the impact of “the clockwork drug,” as my 13-year-old son has contemptuously rebranded cell phones, has had on the quality of academic work, but I can’t help wondering, do people still daydream? Would Einstein have spent his idle hours pondering the laws of the universe if he’d had an entertaining gadget in his hand from the moment he could grasp it? Now I’m sounding like Aoust.

Yes, things are changing. But, in your book, Berkeley seems the same as it’s always been! In addition to evocations of the Berkeley campus and its environs—including the Pacific Film Archive, Caffe Strada, People’s Park and iconic campus landmarks—you also remind us of vibrant protests on Sproul and the closing of the legendary UC Theater. What is the significance of that theater to you and this story?

I lived about three blocks from the UC Theater for four years and went there as often as I could. With a constantly changing double-bill of classic, avant-garde, foreign, Kung-fu, Hollywood, etc. movies every night of the week (in often deplorable prints), plus the ever-present Rocky Horror Picture Show at midnight, the UC Theater was paradise for anyone wanting to see movies they couldn’t normally see, with a lively audience, at rock-bottom prices. Coming from a small town in New Mexico, which only periodically had a cinema at all, I felt like the recipient of vast cultural riches in that theater. I have powerful memories of going in there to see something I’d never heard of and coming out transformed.

I gave these feelings to Professor Aoust (he also feels the same about the Pacific Film Archive, which thankfully is still standing) because the loss of these kinds of theaters, and the communal experience they offered, is symbolic of the broader cultural changes that have transformed society in the past 20 years. Earlier this year, the last of downtown Berkeley’s movie theaters, the United Artists on Shattuck, closed down. When I was a student there were seven. There is no question that the shared cinema-going experience, and whatever it contributed to the broader culture, has been impoverished. This feels ominous to me.

You show a prescience in portraying Professor Aoust as an archetypal figure who finds it difficult to transition to new technologies and expressions of radical politics on campus, much like his inability to adapt to changes in his personal and professional life. Is there a metaphor here?

I’m sure it can be read metaphorically, but the metaphor arises organically from Aoust’s character, not from conscious design on my part. He is a dinosaur. His time, his relevance, have passed, in his personal as well as his professional life. He is divorced, living alone, can’t really relate to his grown American son, teaching stuff the students don’t care about, hung up on a lost film that his colleagues aren’t interested in. But he remains loyal to his passions; he can’t betray them (say by embracing cell phones and streaming videos) without losing something vital to his identity. So he is a mildly tragic figure, albeit rendered in a somewhat comic or ironic vein.

Did you take any inspiration from professors you had at Berkeley?

The only thing I borrowed from a real professor for my portrait of Bernard Aoust was his name, or rather an echo of it. Bertrand Augst (Professor Emeritus) was a wonderful professor in the Film Studies department, a Frenchman with a beard. He was instrumental in the development of the B.A. in Film. Otherwise, Aoust is mostly a hybrid of some elderly gentlemen from India that I know, some bits of myself, and pure imagination.

I did have an English professor who inspired me to become a writer. His name was Julian Boyd. Boyd wore his deep erudition very lightly, so lightly that his classes felt like you were just hanging out with him at a bar, trading stories about the quarks of modal verbs. One day, after handing our graded essays back to us, he said, for the whole class to hear, “James is a good writer.” It’s hard for me to say how much that meant to me, and still does.

You mention Stoney Burke, a street performer and Berkeley mainstay, in the novella. Who were some of the other campus characters you remember when you were a student?

Well, you had Hate Man, usually near the Telegraph Avenue entrance to campus. He was a scrawny old bearded guy with an unclassifiable wardrobe of mostly women’s clothing who said “I hate you” to every passerby because he felt it was more honest than most salutations. Not far from him, amongst the London plane trees, was Rick Starr, who crooned Rat Pack numbers nasally into a powerless microphone, with frequent asides of, “Hey, baby, how ya doin?” etc. There was the “Bubble Lady,” the street poet Julia Vinograd who went around in black velvet gowns and a gold beret, blowing bubbles. There was a revolving cast of hell-and-brimstone street preachers, one who called himself Yoshua. There was a guy with evidence to prove that John Lennon was murdered by the CIA, in league with Stephen King. One of the most enigmatic characters was the woman who walked her goat and pig and two dogs around the campus like some roving allegory.

You are now an expatriate, not only of Berkeley but of America. Where did you write this story and did the distance matter in how you remembered and wrote about the campus and its environs?

This story was born in a cafe on the outskirts of New Delhi (as a thread in a different story born in a cafe in Paris), grew a little in Edmonton, Canada, gained some weight in Liverpool, England, before finally reaching full maturity in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Certainly, time and distance matter in how one remembers things. I wanted to write a kind of love letter to Berkeley, which remains one of my favorite places on Earth, because I fell in love with it at 18 and probably would have stayed there forever if the exigencies of life hadn’t intervened. Time and distance make the vital things sparkle.

Deven Patel is an associate professor of Sanskrit and South Asian Studies, as well as the Director of the Comparative Literature Program, in the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. He holds a Ph.D. in South and Southeast Asian Studies from UC Berkeley.