Resist and assist: A tidy couplet that captures the spirit of Anti Lab, a self-described “resource center for creative resistance” whose uses, like its political stances, are multiple. Anti Lab, which opened in Oakland in April, is an exhibition space for local artists, a meeting place for organizations that don’t have their own, and a hub for visitors to make use of free art supplies or grab a cup of coffee. It’s also the brainchild of UC Berkeley grads Sarah Burke and Holly Meadows-Smith, close friends who began collaborating on the project in the weeks following the inauguration.

In one corner, a reading nook is stocked with a “library for liberation,” a curated selection of books and essays on alliterative themes including “Questioning Capitalism” and “Forming Feminism.” On a wall there is a banner by conceptual artist and Cal assistant art professor Stephanie Syjuco that reads, “No bigotry / No racism / No hatred / No business as usual / Resist!” A dozen or so posters by other artists fill the same wall. “Good night ‘Alt’ Right” reads one. Further down, there’s another rhyme: “Resist fear, assist love.”

All of this—the supplies, the literature, the caffeine—is free. So are the workshops, held several times a week for the project’s six-week duration. The roster of events includes a tenants’ rights workshop hosted by the East Bay Community Law Center, a three-part protest medic training, several afternoons dedicated to silk screening and film screenings—just about everything from A to zine-making, which, of course, is possible too.

Anti Lab marks the first professional collaboration for Burke and Meadows-Smith, who have been friends since they met in their first year at Cal. While working together hasn’t posed a problem for their friendship, mounting the project has been a sort of endurance test. Planning for Anti Lab only really got underway in February, leaving the pair about two months to secure a space, find funding, and reach out to local artists and organizations. Anti Lab will remain open until May 13, and until then both Burke and Meadows-Smith will continue to work their regular jobs (Burke is a freelance writer and Meadows-Smith works in business development) as they oversee the space each day that it is open.

“I’ve been telling people I feel like I’ve been doing a durational performance,” said Burke when I spoke to her and Meadows-Smith about a week after the Anti Lab launch party. “We had no sense of the extent to which people would actually utilize the space and yet immediately, right off the bat in the first week so many people … have come in and used the space in ways that we didn’t even anticipate. It’s been wild.”

… Anti Lab is unified under the mantle of what Burke calls “aesthetic disruption”—a set of challenges to the status quo.

Some of the unexpected uses included a recent visit from members of Cal’s newly formed Undergraduate Workers Union, who spent the day making patches and pins. “It was cool because they’re not longtime organizers, they’re literally just students,” said Burke. “They’re learning about labor organizing step-by-step.”

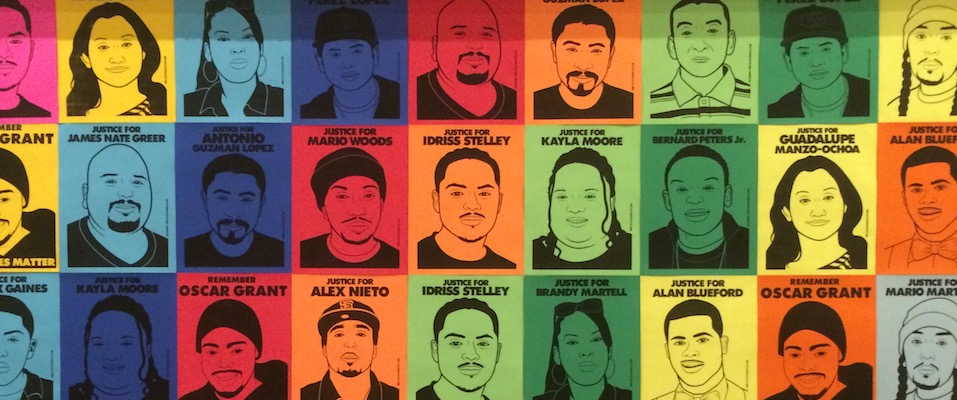

For Burke, a well-known local art critic and former East Bay Express managing editor, the choice to frame Anti Lab as a resource center rather than an art show was intentional. This isn’t because art is not an integral part of the project (it is, after all, made and displayed there), but because art at Anti Lab is unified under the mantle of what Burke calls “aesthetic disruption”—a set of challenges to the status quo. A sign by the door explains the project’s mandate: “Anti Lab is an open resource center for creative resistance projects that are anti-fascism, anti-racism, anti-patriarchy, anti-transphobia, anti-xenophobia, anti-capitalism, and anti-complacency.”

At Anti Lab, forms of “creative resistance” may have radical applications, but the idea of art-as-activism is nothing new. Political artmaking has helped popularize everything from the gay pride flag to the Black Power fist to the coat hanger as a symbol of reproductive justice. Creative resistance projects have had a hand in shaping social movements ranging from the fight for women’s suffrage (to which artists at the turn of the 20th century contributed banners, postcards, and illustrated pamphlets) to AIDS activism in the 1980s and 1990s, which fomented around the SILENCE = DEATH logo created by six activists in 1987.

Banners, buttons, and bumper stickers have long been a means of expressing solidarity, circulating ideas, and garnering visibility—all critical parts of any social movement. According to Stephanie Sjyuco, these effects may not be directly measurable, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t valuable. “It’s hard to quantify what a sign does,” she said. “But in this era in which images travel quickly—whether it be on the internet or on social media or through the news—it’s shockingly powerful how the right image at the right time can make a huge impact.”

Syjuco started making banners like the “Resist!” one on display at Anti Lab in the aftermath of the presidential election. “As an artist I wound up taking a step back and thinking about a whole history of visual signage, banners, things that artists in other movements had created,” she said. “I wanted to generate visual evidence of the moment.”

One of the pieces she made was a 12-foot-long black banner emblazoned with the words #DefendDemocracy. It ended up in the hands of author and Cal alum Rebecca Solnit, who was seeking out banners for an anti-Trump protest she was leading at the California State Capitol in December.

For Solnit, as at Anti Lab, the umbrella of civic engagement is a broad one. As she explained in a recent interview that revisited her book Hope in the Dark, written during the Bush administration, “You don’t have to make political art … Maybe your job is to write beautiful apolitical poetry and also register 1,000 people to vote.” In other words, there’s no reason why phone banking and banner-making can’t coexist.

This is part of why Burke is grateful to be staging Anti Lab in the Bay Area, where she says most people already think of art and activism as natural complements. Even so, she says that she and Meadows-Smith were mindful of publicizing the project beyond the East Bay art scene in order to attract as broad an audience as possible.

“It was basically this impossible riddle, because we wanted [Anti Lab] to seem both really accessible and appealing and welcoming, but at the same time, not seem totally toothless,” she said. “We wanted it to seem like this is a serious place for actually doing important things.”

Part of solving that riddle was coming up with the name “Anti Lab,” which Burke said was the first step in conceptualizing the project’s mission. That the name positions Anti Lab as a space against is something of which the pair is mindful. “There is this pressure to not be negative, which I totally understand,” Burke said. “But at the same time, for people who are harassed and oppressed, it can feel the most safe when a space is very explicitly against the things that are oppressing you. [We want] to make it as clear as possible that anyone who is any of the things we listed: transphobic, racist, whatever, are not going to be allowed in the space.”

In recent years, critics of campus politics and of the left more broadly have often targeted anyone who suggests pairing the word “safe” with “space,” railing against the notion as a kind of hypersensitive cloistering at best or else a sure agent of intellectual atrophy. But at Anti Lab, it’s really a way to ensure common decency and foster accountability among a diverse group of visitors working within a common political framework.

Given the widespread community support for the project, this framework is also much-supported one. In addition to a $1,000 grant from the Awesome Foundation’s Oakland chapter (the foundation oversees a number of independent, community-funded grants allocated by local members), the space is supported by donations from a number of local businesses and organizations. These include Anti Lab’s host, Oakland’s Gallery 2301, whose founder Thomas Don has welcomed the resource center to transform the gallery and take up residence there free of charge.

Burke and Meadows-Smith’s personal connection to the East Bay arts community is also echoed in Anti Lab’s dedication to the memory of Ara Christina Jo. Jo was a friend of Burke and Meadow-Smith’s and a well-known member of the Oakland art and music scene who died in December’s Ghost Ship fire. “Ara was a DIY queen,” said Burke. “She could make something out of nothing in this really magical way.”

“She would have been a perfect person to have on board and who would have been stoked about the project,” Meadows-Smith said. “It seemed right to acknowledge her and her inspiration and impact on us and the project.”

Jo was an active member of the Rock Paper Scissors Collective, a volunteer-run Oakland artist group that, like Anti Lab, emphasizes community projects and skill-sharing. In conceiving of Anti Lab, Burke was particularly inspired by a recent spate of DIY project guides that had been circulating online, including Stephanie Syjuco’s guide to making fabric protest banners. The 42-page manual includes instructions for recreating the #DefendDemocracy banner that Syjuco made for Rebecca Solnit, as well as the “Resist!” banner now on display at the very space it helped inspire.

“I was excited about these projects that could take on a life of their own and didn’t have to be tethered to a single author,” Burke said. “The idea was that once people were in the space making these projects, then we could keep them there and engage them in more practical programming.”

Practicality was certainly at the center of the protest medic training I attended one Sunday, a precursor to a three-part series of hands-on workshops took place over the next few weeks. Leading the trainings is Elle Armageddon, a Bay Area native and practiced medic who has been participating in protests since 2011. Armageddon is a skilled facilitator who spoke eloquently on topics ranging from the chemical composition of tear gas (apparently weaker these days) to Fourth Amendment rights for protesters (also weaker, as it turns out). Over the course of the three-hour workshop we covered everything from best cybersecurity practices for activists to how to counter the effects of tear gas to what do if a medical emergency like a punctured lung is suspected.

For most protesters, injuries are not a desired price of participation, but one only needs to read about the violence at February’s clash over Milo Yiannopoulos or April’s Free Speech Rally to know that they are an unfortunately common outcome. In leading workshops at Anti Lab and elsewhere Armageddon hopes to pass on the knowledge she has learned in her six years (by her own account, an unusually long run) doing medic work. I asked her what, in an ideal world, the medic to protester ratio would be. “When everyone out in the streets is trained and carrying a first aid kit—that’ll be almost enough,” she said.

For many of the participating artists, too, the idea of a united citizenship armed for the resistance is a guiding ideal. Angie Wilson, an Oakland-based textile artist, hosted a protest curtain-making workshop at Anti Lab in late April, an idea that came to her after working on banners for the Women’s March and other actions. One of these banners is on view at Anti Lab, with “Never Again is NOW” emblazoned in red letters on a gingham and floral background—the same curtain fabric, Wilson explained, that she uses in her home.

“I led some workshops at my house and I was thinking that it would be really great if those banners that we made could be put in our windows and double as curtains,” she said. Wilson was struck by the idea of harnessing the visual power of banners to form a sort of “mural on the street,” with a sea of protest curtains conveying their messages to passerby. “In between actions they could face the street,” she explained. “That way we could be communicating these empowering messages all the time.”

Burke described her initial inspiration for Anti Lab in an almost identical way. In the weeks following the presidential inauguration, she found herself wondering how to express resistance to the new political climate and spur on more tangible political engagement among her peers, many of whom were participating in actions like the Women’s March in unprecedented numbers. “I started thinking about this idea of: What if we could fill the streets? With banners and wheat-pastes and posters that really make it impossible to be complacent and really make it impossible to forget what’s going on,” she said. “What if we could produce so much aesthetic disruption that no one would be able to forget the injustice that was happening?”

Burke and Meadows-Smith want this sort of disruption to live on after Anti Lab, which is why they are putting together a “How-To Anti Lab” guide to make the project’s model replicable and transparent for others interested in creating resource centers of their own. A nod to the DIY, open-source guides that inspired Burke in the first place, the book will cover each stage of the planning and execution process, as well as any missteps they feel they’ve made. “The intent is not to [suggest] Anti Lab is perfect, but rather to offer a blueprint for people to improve upon,” Burke said. At the Anti Lab closing ceremony on May 13, the book will be packaged up along with other resources and sent to galleries and artists across the country.

The closing ceremony will also include the smashing of the colorful, streamered piñata that hangs from the middle of Anti Lab’s ceiling. The hand-made piñata, which takes on the traditional seven-point shape, is part of conceptual artist Sita Kuratomi Bhaumik’s project Estamos contra el muro | We are against the wall and was custom-made by Piñatas Las Morenitas Martinez. Each point, Bhaumik explained, represents a sin, and the destruction of the piñata represents triumph over evil.

At Anti Lab this triumph is not taking place in religious terms, but in political ones, in which the seven deadly sins (fascism, racism, patriarchy, transphobia, xenophobia, capitalism, and complacency) have been redefined for social justice praxis. Leading up to the ceremony, visitors to the space are prompted to fill out two forms, which will be added to the piñata before it is broken.

“If you could destroy anything what would it be?” the first asks. “If you could build anything what would it be?” mirrors the second. At the opening I grabbed my twin slips and wandered away, unsure of what to write. At the far end of the room, a mounted poem offered counsel:

THIS IS NOT A

TIME FOR

DISBELIEF

THIS IS A TIME

FOR NEW

BELIEFS

A TIME TO

REMAKE

THE IMPOSSIBLE