During World War II, some of the most important work connected with UC Berkeley was done not in a library, lecture hall, or lab—but from within the barbed-wire confines of internment camps.

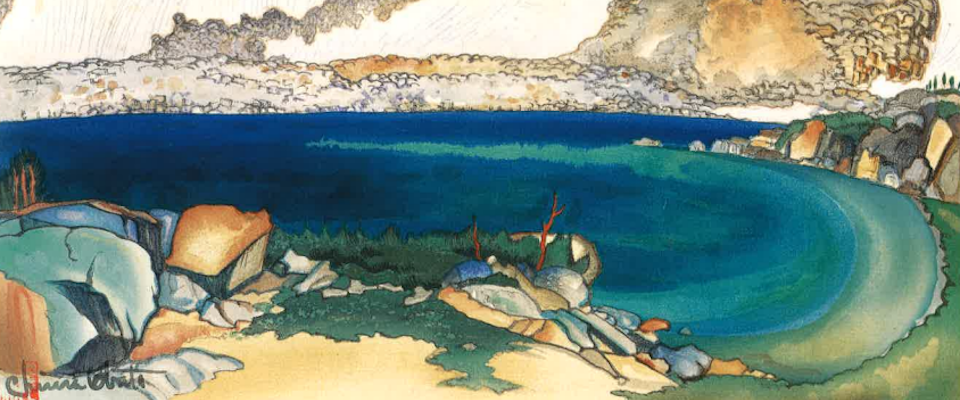

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942 mandating the removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the western United States, one of the lives he upended was that of Cal art professor Chiura Obata. An artist trained in traditional Japanese techniques but enamored of the American landscape, Obata’s paintings, woodblocks, and sketches serve as a powerful visual diary not only of how the experiences looked, but more importantly, how they felt.

Of his internment in the desert—and the spiritual deprivation that accompanies confinement and exile—Obata once said: “If I hadn’t gone to that kind of place, I wouldn’t have realized the beauty that exists in that enormous bleakness.”

This year, several of his paintings of the internment are being added to the collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Others of his works can be seen at the Oakland Museum of California’s Gallery of California Art.

“He stands as an indictment of our very worst human tendencies,” says Cal alum and San Francisco State associate art professor Mark Johnson, “while his resilience and generosity serves to remind us of the value of being open to diverse perspectives and expressions.”

We’re accustomed to thinking of painters as free-spirit bohemians, but Obata, who grew up in Japan, studied art with the calculation and forbearance of a NASA engineer. Artists of the era were expected to make their own brushes, know the values of a menagerie of furs and woods and prepare their own pigments (a paint made from oyster shells required no less than two years to create). Obata had to spend several years tracing circles and lines before he was permitted to draw the parts of flowers.

“Collecting unusual trees, bonsai-like greasewood, unusual stones, and topaz gives relief from the meaningless barracks life.”

When his older brother Rokuichi enrolled him in military school, Obata ran away to Tokyo, and from there kept running, creating a broad portfolio of work before migrating to the West Coast of the United States in 1903. “The greater the view, the greater the art; the wider the travel, the broader the knowledge,” he explained to his father. For several decades Obata supported himself through commercial work, until in 1927 he took his first trip to the Sierra with his friend and UC Berkeley art professor Worth Ryder and sculptor Robert Boardman Howard.

Until then, Sierra- and Yosemite-inspired artworks had been largely sentimental Renaissance pastiche: empyrean vistas that had more in common with the Sistine Chapel than the valley itself. Obata’s work focused instead on the simplicity of a scene, the bare elements that worked together to make the great view. This was a common theme of his work: not just nature—shizen—but great nature—dai-shizen. His paintings and woodblocks are of spare lines, or a small cluster of trees, or a few orange squares of firelight seen through the window of a distant cabin. What gave his work its greatness was its utter intimacy with nature—the same sensibility Ansel Adams would use in his first iconic images of Half Dome made that same year.

“Worth Ryder and Robert Howard did sketching in the mountains, but maybe just two or three pieces,” Obata said of the experience. “During that time sometimes I worked until 2:00 in the morning and completed almost 150 pieces of detailed sketches. I could do this because every day was another impressive experience.”

He later spoke to Ryder’s class at Berkeley, drawing as he lectured:

“I put up a long piece of paper—3, 4, or 5 feet wide, and on the paper I drew the High Sierra from Yosemite’s Oak Flat Road, gradually going to the top of Glacier Point, and to Tuolumne Meadows. I let my brush draw spontaneously and at the same time I went on talking and talking. It must have made an impression on the students. To tell you the truth, the students said they really wanted to learn from me and they requested a class.”

In 1930, Obata and his wife, Haruko, opened an art supply store on Telegraph Avenue. He became a summer instructor at the university and eventually a full professor in the art department, making UC Berkeley the first university outside of Japan to offer Japanese art as a discipline. “I always teach my students beauty,” he said. “No one should pass through four years of college without being given the knowledge of beauty and the eyes with which to see it.”

The experience of the artist, he felt, is central to the experience of the art. A small example of this can be found in a story Obata told about how to paint the moon:

“I said I would go to the Santa Cruz Mountains to watch the autumn moon. My students said, ‘If you just want to see the moon, you don’t have to go that far. You can see it from here.’ So this is the point: You go to the Santa Cruz Mountains and in those deep mountains you wait for the sunset and you hear the sounds of the bellsinger cricket and then slowly, from behind the woods, the moon emerges. That atmosphere is beyond expression. I feel this is the blessing of Great Nature.”

And then, almost overnight, everything changed. Pearl Harbor launched Obata’s adopted country into war against the country of his birth. Neighbors turned suspicious. Customers abandoned his work. Students were reluctant to take his classes. Then came vandalism, gunshots, and posters with large unfriendly lettering: “Instructions to all persons of Japanese ancestry…”

Obata was forced to cancel classes and close the art store. The family sold his paintings, woodblocks and art supplies, donating the proceeds to the university for the establishment of a scholarship for any art student, regardless of race or creed.

A small but vocal alliance of prominent Bay Area citizens formed The Fair Play Committee, which fought against discriminatory cultural and legal practices. UC Berkeley president Robert Gordon Sproul and provost Monroe Deutsch were both members. However the committee was too small to be effective against the larger tide of war fever: They tried and failed to prevent the internment, then to exempt the Obatas. When that didn’t work, the Sprouls offered to store Obata’s remaining paintings, and tried to relocate the family to Yosemite.

But the bureaucratic machine ran too slowly, and by the time a Yosemite relocation could have been made real, a new law was passed effectively barring Japanese Americans from access to the park. So having surrendered their property, their business and their careers, the Obatas were relocated to Tanforan Detention Center in San Bruno.

It was April 30, 1942. After seeing a child playing at the edge of the street on the day they were rounded up and shipped to Tanforan, Obata wrote: “This is a kind of sin which is intolerable. From this sin, we have to bring these school children back to equality. We have to do something about it. My first thought was to open an art school and start teaching everybody.”

Officially, Tanforan was a “transfer point” until the War Department could figure out what to do with the thousands of citizens it had sent into exile. It was also a converted racetrack and stables, linoleum thrown down hastily over the dirt floors and bedsheets strung up for privacy. A few of Obata’s former students from Berkeley came to visit Tanforan, but were barred from entry and met their professor at the fence. It had always been important to Obata to remind his students not just what to look at but how to see, and he used the moment to teach a final lesson. Haruko Obata remembered the scene:

“Oh, they would cry, poor things. They would say, ‘Oh, Professor Obata, you are behind the fence!’ And he would answer, ‘From my perspective it looks like you are behind the fence!’”

Together with fellow inmates Mine Okubo, George and Hisako Hibi, and another 20 artists, Obata created the Tanforan Art School, and later, once relocated to Utah, the Topaz Art School. The instructors offered lessons in contemporary and traditional art to more than 600 amateurs and professionals, from children to elders.

The artists became documentarians of sorts: Internees were forbidden from having cameras.

“They were making real deliberate choices within their styles of what they were including,” notes Obata’s granddaughter and biographer, Kimi Kodani Hill, author of Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment. She points out that Obata sometimes painted a scene with, say, an internee much closer to a fence or a tower than would have been allowed—a compressed perspective that captured more truth. “When we look at photographs of the family,” Hill says, “there’s a big hole in the war years. And the same happened to us [the descendants] with the emotional interpretation. There’s a hole.” The details an artist chooses to add or subtract may fill that hole. “They show how people were coping with their dignity intact.”

For a man accustomed to spending his free months traveling outdoors, perhaps the worst part of the confinement was boredom. The art schools helped provide purpose to the otherwise mind-numbing routines of internment. “Collecting unusual trees, bonsai-like greasewood, unusual stones, and topaz gives relief from the meaningless barracks life,” Obata wrote.

Ironically—considering he was imprisoned for his Japanese ancestry—Obata not only continued his recognizably Japanese-styled work, but was celebrated for it. He continued with his sketches, creating many new works a week—pieces capturing the austerity of the camps and the grim dignity of the disabused. Even while he was still incarcerated, the art he created was displayed in Berkeley, Oakland, and Pasadena.

In 1943, the government introduced loyalty oaths. First-generation immigrants were reluctant to sign because the oaths required them to renounce their Japanese citizenship. Second- and third-generation Japanese Americans were insulted by the notion that they, as natural-born citizens, should have to affirm allegiance to a democracy that was doing nothing to defend them. Obata considered it in the best interests of him and his family to sign—an act for which he was severely beaten by some fellow inmates.

After hospitalization, he was moved to St. Louis for his own safety, where his son Gyo was already a student at Washington University in St. Louis (Gyo would go on to become the head designer and the ‘O’ in the international design firm HOK, and his works include the National Air and Space Museum. The nonsensical reason Gyo was living free in Missouri while the rest of the family was interned in Utah: Only Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were interned.)

At last the war ended, and Chiura Obata resumed his faculty post at UC Berkeley and collected the artwork the Sprouls had safeguarded for him. But Obata and his wife lived in an attic apartment until the 1950s, when they could again afford to purchase a house in the same neighborhood where their home had been taken from them. He retired from Cal in 1954 and led summer enrichment excursions to Japan until six years before his death at age 90 in 1975.

While Obata would not live to see a proper apology for the grave injustice of the internment camps, Haruko and three of his children would. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, legislation that offered reparations to the then more than 100,000 survivors of the internment—but also said “It’s not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes.”

The greater mistake, however, may be to think that we will invariably make better choices—a point worth bearing in mind given that today, significant numbers of Americans now say they support racial profiling, closing U.S. borders to immigrants, and segregating in near-perpetuity refugees from some other countries.

History’s acts of mass injustice have rarely been committed by evil people, but more often by fearful ones. The U.S. internment of Japanese Americans was not an earthquake or tsunami or some other force of nature. It did not just ‘happen.’ People made sure of it. And just as certainly the people inside those fences—Obata, the 23 art instructors and the more than 600 art students at Topaz and Tanforan—made sure it wouldn’t destroy them.