Unless you’re a hardcore baseball fan, you’re likely unaware of the new rules coming to Major League Baseball in 2023. These include a pitch clock, bigger bases, and restrictions on pickoff attempts to encourage more base-stealing. Why the changes? Longer games with fewer safe hits and stolen bases have proven unpopular with fans, and baseball’s popularity has continued to decline relative to pro football and basketball.

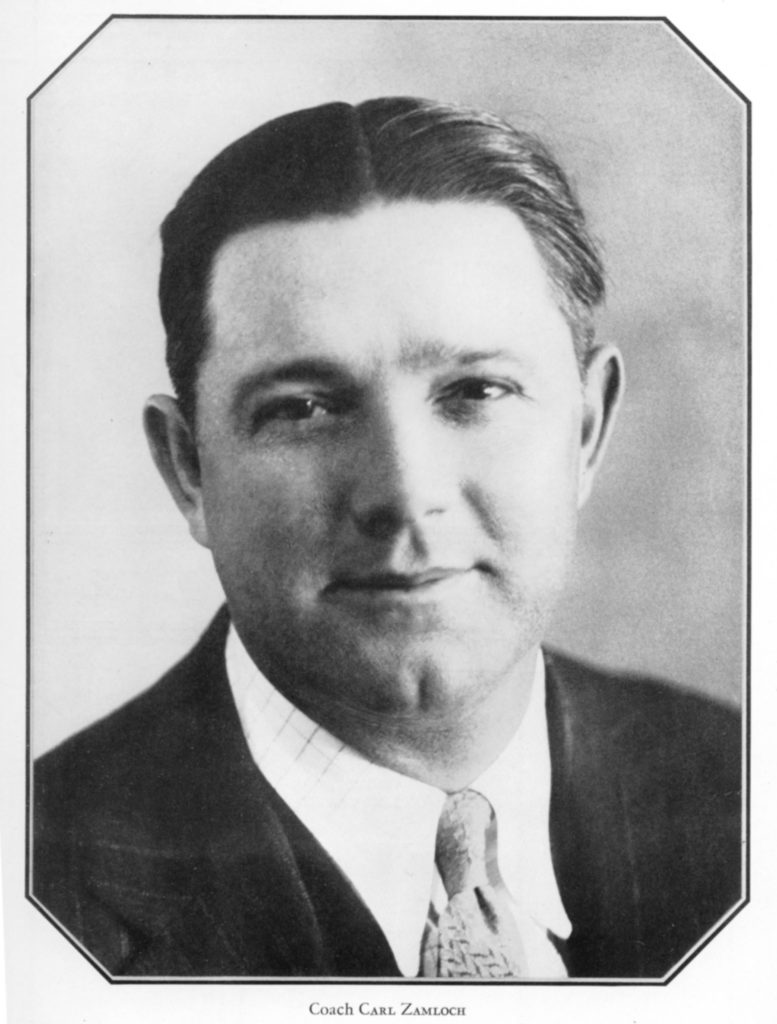

While MLB execs might think they are taking bold and timely action to save the game, a visionary Cal baseball coach beat them to it by almost 100 years with a move that was even bolder. In 1928, Bears’ skipper Carl Zamloch made national news by proposing a far more drastic rule change. He called it “reversible” baseball.

Sometimes referred to as “left-handed” baseball, Zamloch’s reversible game gave batters the option of running to either first base or third base after putting the ball in play. Fielders had to take note of where the batter was going and adjust accordingly. If a batter chose to run to third base and reached it safely, all offense in that half inning was reversed and subsequent runners advanced clockwise.

Zamloch—the son of a world-famous magician and a noted vaudeville performer in his own right—felt strongly that baseball needed to be more entertaining. “Baseball has not increased in popularity in comparison with our population. Football has made wonderful strides,” he said. “I think that is partially because the fans can anticipate the play. In baseball we all know that when a man singles. . . he is going to first base. If we mix that procedure up a bit it ought to increase the interest.”

Zamloch proposed reversible baseball rules in the Bears’ annual contest against the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks, but Oaks official Del Howard wasn’t having it. “If these college boys want to play baseball with us we’ll entertain ’em, but if they want to play some funny game invented by Coach Zamloch, then that is something else again,” Howard harrumphed. “How do I know what they may do after running from the plate to third instead of first? Maybe the next rule calls for skipping second base, taking a cup of tea or reading a book or something . . . I’m certainly not going to let the Oaks play left-handed baseball.”

Zamloch eventually convinced a semi-pro club called the Ambrose Tailors to play an exhibition on February 15th, 1928, and in the weeks before the game the national and local press devoted considerable space to debating the merits of Zamloch’s idea. As a result, observed the Oakland Tribune, a contest that normally would have generated little interest drew “a crowd of 500 fans, two motion picture cameras, and four newspaper photographers” to the Berkeley diamond.

The Tribune called the contest “an uproarious success in more ways than one.” In the bottom of the first, Cal catcher Walter Wyatt walked, went to third base rather than first, then stole second. Pitcher Gus Nemecheck came to the plate and promptly knocked the ball out of the park, “but from force of habit he started trotting toward first when the ball was hit and [he] was declared out just as the sphere sailed over the fence.” As the Berkeley Gazette noted, he thereby “won the honor of being the first person in baseball history to knock out a home run that wasn’t even a hit.”

The Bears did not have a monopoly on reverse misplays. “Three times during the game, [Tailors’ third baseman] Bill Marriott … was caught napping and runners were safe at third when Marriott started to throw the ball to first.” Other highlights noted by the Tribune: watching the Tailors’ infielders attempt a “reversible double play” (second to third, presumably) and the reactions of passers-by “when they saw men being run from first to home.”

Cal built a 9-4 lead through seven innings before the clubs agreed to revert to traditional rules. The Bears quickly blew their lead, falling behind 10-9 before rallying in the bottom of the ninth for a walk-off 11-10 victory.

In the end, reviews were mixed. The Los Angeles Evening Express opined “Zamloch’s left-handed game would add an element of surprise, hidden thrill, genuine deception to a game that is now just one, two, three—you’re out.” The San Francisco Examiner, meanwhile, demurred: “Baseball has been getting along fairly well for quite a few years, thank you. Let’s confine ‘new ideas’ to ping-pong or something like that.” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette was more succinct: “Baseball has done well as it is. Let it stay the way it is.”

While the idea generated plenty of commentary, what it didn’t generate was more games. By the 1920s baseball was already a sport steeped in—some might say trapped by—its own tradition. Reversible baseball was relegated to history.

That may finally be changing. Indeed, the rule changes on tap in 2023 are being hailed as a breakthrough by pundits who predict they will make the sport more entertaining and reverse its slide in popularity. That’s one possible outcome. More likely, though, baseball will need to take additional steps to add excitement and win back fans. If that proves to be the case, perhaps baseball—like so many other businesses and institutions—will look to Cal as a source for innovative solutions. Perhaps they’ll dust off Carl Zamloch’s radical century-old proposal and adopt reversible baseball.

Dan Schoenholz (BS ’85, MPP ’98) is Community Development Director for the City of Fremont and a lifelong Oakland A’s fan.

Cal Baseball opens its 2023 season in Houston on Feb. 17. The Bears’ first home game will be on Feb. 24, at Evans Diamond, against Cal Poly.