In 1976, Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner tapped Joan Didion to cover the Patty Hearst trial. What a match-up. What a saga. California royalty caught in surreal counterculture chaos, narrated by a star of the New Journalism, herself a daughter of the Golden West.

Didion signed on, and announced that she wouldn’t be spending much time in the courtroom.

“Wenner seemed dismayed,” writes Tracy Daugherty in The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion, published in August by St. Martin’s Press. “But Didion insisted she was thinking of Hearst as an idea of California rather than a defendant in a trial. She said she would probably spend more time in the Bancroft Library.”

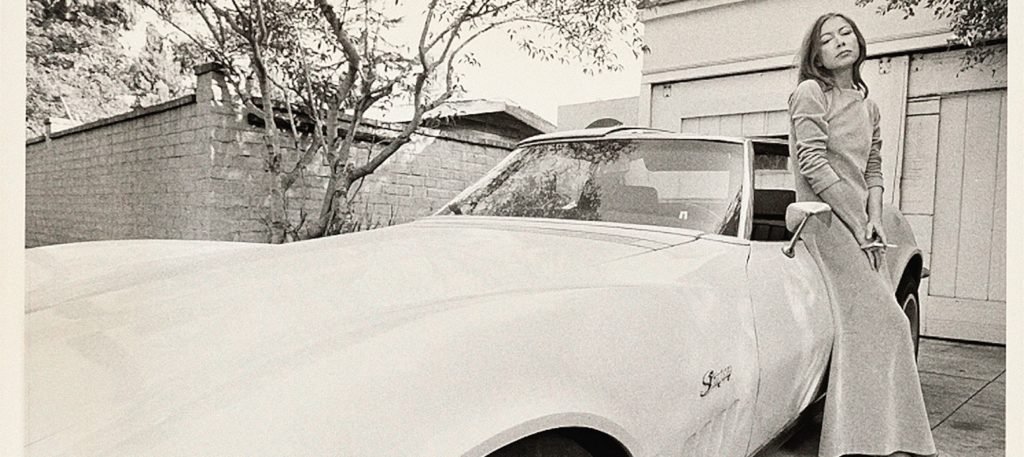

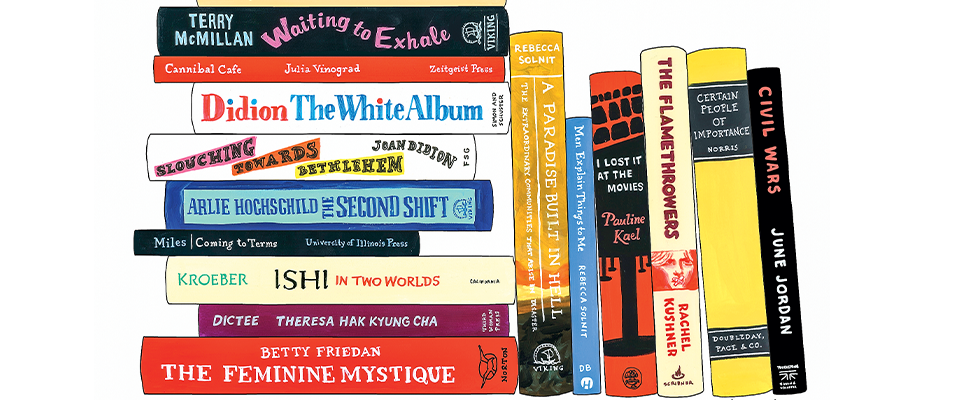

The essay never made it to Rolling Stone. “Girl of the Golden West” ran in The New York Review of Books, and still is considered one of her best. And the Bancroft remains a kind of magnetic north for all things Didion. She graduated from UC Berkeley in 1956. In 1981, she and her husband, author John Gregory Dunne, both donated their papers to the Bancroft. And when Didion, who is now 81, accepted the 2006 Hubert Howe Bancroft award, she said: “Even as an under-graduate.…(the library) represented something to me. It represented a belief in the value of the past … in the value of the rare, the unique, the few. It represented the continuity of those values in a culture and a state more famously focused on the future than on the past.”

In fact, if not for seven neat white boxes comprising the Joan Didion papers at the Bancroft, containing her past from 1963 to 2006, the new biography might not exist. When Daugherty began work on the book, Didion chose not to participate. Her daughter Quintana had recently died, on the heels of Dunne’s sudden death. (Didion chronicled those losses in The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011).

“I depended heavily on archival materials,” Daugherty said, “which is why the Bancroft was so important to me.” A professor of English and Creative Writing at Oregon State University and author of four novels, four story collections, and a book of essays, Daugherty followed the research methods he had used on his previous literary biographies of Joseph Heller and Donald Barthelme. The result has earned enthusiastic notices.

“It is rare to find a biographer so temperamentally, intellectually, and even stylistically matched with his subject as Tracy Daugherty…is matched with Joan Didion,” wrote Joyce Carol Oates in a recent issue of The New York Review of Books.

The biographer “practically establishes a psychic connection with Didion,” the Christian Science Monitor suggested in one of the book’s earliest reviews.

“My primary interest was in tracing Didion’s literary evolution,” Daugherty said recently, in an interview conducted via e-mail. “By studying her rough drafts, I was able to discern how painstaking a craftsperson Didion is. Sometimes the smallest grammatical changes in a draft could alter her entire vision for the book,” he noted. “Her novel ‘Democracy’ is a prime example. She started the book over and over, from different points of view, and little by little, through small as well as larger changes, switched the book from a novel of manners to a much more political document.”

Tracking the path of Didion’s thinking is one of the pleasures of reading her work. A trip through her archives offers intimate views. Among manuscripts and page proofs, a slim folder labeled “Book of Common Prayer” holds two spiral-bound notepads and two maps of Panama, the corners of which are still sticky with tape. (Perhaps they hung over her desk as she conjured the fictional setting of the 1978 novel.) Each dog-eared notebook is half-full of pencil-jottings. They seem to have been made “in country,” since Didion’s polite cursive—she crosses t’s with a parachute, a curved line that floats—is in spots difficult to read. Here, the writer can be seen exercising themes and building atmosphere through snippets of dialogue (“Could she recommend a history of Panama/ Panama has no history, she said”), lists of observations (“Where nothing quite works or fits. The hotel stationery is too big for its matching envelope by one-eighth inch. Railroad track of differing gauges”), and opaque reminders (“Find Grace”—that is, locate the narrator.)

There’s a hush in the Bancroft Reading Room at the end of the day. Researchers surface from myriad worlds, and cross the cork floors to return boxes of archive materials. On the walls hang oil paintings, gifts to the Bancroft. California landscapes—almond groves, grazing cattle. Looking through the arched windows to the green panorama, it’s not difficult to imagine Didion on campus in 1953. In some of her most personal essays, she indelibly painted her undergraduate life.

“On the Morning after the Sixties,” written in 1970, begins with a memory of another moment when everything teetered on the brink of change:

An afternoon early in my sophomore year at Berkeley, a bright autumn Saturday in 1953. I was lying on a leather couch in a fraternity house (there had been a lunch for the alumni, my date had gone on to the game, I do not now recall why I had stayed behind), lying there alone reading a book by Lionel Trilling and listening to a middle-aged man pick out on a piano in need of tuning the melodic line to ‘Blue Room.’ ….That such an afternoon would now seem implausible in every detail—the idea of having had a “date” for a football lunch now seems to me so exotic as to be almost czarist—suggests the extent to which the narrative on which many of us grew up no longer applies.

It is not too much to say that Didion launched her career from Berkeley. In 1955, as a junior, she submitted a short story to Mademoiselle and won a coveted slot as one of ten summer guest-editors. She flew to New York—her first trip by plane—with Peggy La Violette, a friend from the Daily Cal who also won a guest-editor spot. At the end of the summer, Didion took the train back to California, typing a series of letters to her friend.

“The letters I received from Joan were long, beautifully written on onionskin paper on her portable Olivetti and mailed from train stations along the way,” says LaViolette Powell, now 82.

She donated the trove to the Bancroft, where they fill the last of the seven white cartons. Daugherty’s biography makes good use of them.

“However reticent Didion may have appeared publicly,” Daugherty writes, “the letters reveal a brash young woman sure of her intelligence and charm, impatient with most strangers, whom she considered commonplace and uninteresting. She was posing in the letters,” he noted. “But she was also certain of her ambition and talent.”

Determined to return to New York, Didion entered another contest for young writers—Vogue’s Prix de Paris—and she hurried through her senior year.

The prize was two weeks in Paris. Didion won, but she wanted New York. She asked for a job at Vogue instead of the trip, and was hired at $45 a week. It was 1956. She was 21.

By day, she wrote fashion copy for Vogue. By night, in a tiny Manhattan apartment, she penned her first novel, Run River, set in California. The die was cast.