Feeling exhausted and overwhelmed by the frenzy of holiday obligations, the frazzled nature of strained relationships, the crush of year-end job demands? As 2013 comes to a close, you’re in good company if you label what you’re experiencing “burnout.”

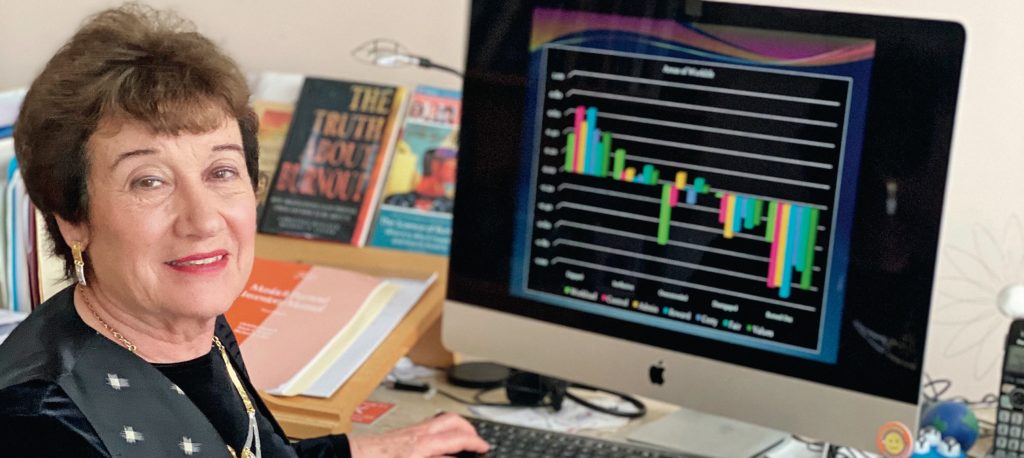

It has been close to forty years since UC Berkeley psychology professor emerita Christina Maslach first applied the trope “burnout” to extreme occupational stress. Since then her diagnostic tool, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, has been the standard means for gauging the precise degree of alienation and ennui engendered by the dreary business of making a living.

Her work has disseminated so widely that “burnout” is now applied to any number of less-than-idyllic scenarios: holiday burnout, for example, or marriage burnout. But Maslach takes some issue with such broad usage.

“ ‘Burnout’ has become a popular term rather than a theoretical or clinical term,” she said. “I think the reason it caught on is that it really seems to capture an emotional state—people feel burned out when their stress levels climb, and that’s why it seems appropriate for such a wide variety of situations. But from my perspective, it is most properly applied to the workplace.”

Holiday stress, after all, is as transitory as the holidays themselves, and marriage—well, your survival doesn’t necessarily depend on it. You don’t need to be married to eat, but unless you’re a member of the Lucky Sperm Club or you hit it big on Powerball, you must work to stock the refrigerator. And it is that unavoidable dictate, the necessity of work, that can lead to burnout. It feels like there’s no way out—for the simple fact that for most of us, there isn’t.

What factors contribute to burnout? Maslach’s Inventory relies on five long-standing indicators and one relatively new one:

Demands: How difficult is your work? Are the deadlines onerous, are the production requirements crushing?

Control: Or lack of it. “Stress levels climb when people feel they have no input, no power over the direction of their job,” Maslach says.

Feedback: “People need to know their work is appreciated. Burnout can be minimized by rewarding good performance,” she says. “That can be money, but we’ve also found that praise is a very powerful motivator.”

Community: Sartre said hell is other people, and the American workplace seems to confirm that. “Colleagues, bosses, subordinates, vendors—how well you get along with them figures significantly into job satisfaction,” Maslach says.

Fairness: How often a brown-noser claws past you on the way up the corporate ladder will play a major role in determining your burnout index. As Maslach notes, “People need to feel the playing field is level.”

Values: This is the newest metric, and Maslach observes that it is increasingly important in the mobile and highly independent workforce of today. “If you’re of a Machiavellian bent and you find yourself in a company that puts more emphasis on results than ethics, then you won’t feel particularly stressed,” she explains. “On the other hand, if you consider yourself a highly moral person, your stress levels could be extreme.”

Given Maslach’s indicators, young Digerati may be particularly vulnerable to burnout. Digital culture is Darwinian and thus unsympathetic to anyone who can’t hack it, so to speak.

“There can be a lack of community in (computer or web-centric enterprises),” she says. “For many people in this industry, work is everything. They may not have rich social lives or many outside interests, and their family connections may be tenuous. So if things go bad at work, it can hit them extremely hard. Or top of that, the culture demands transparency and complete accessibility. You have to be available through your electronic devices at all times. There is little or no privacy. So burnout is a very real risk.”

What to do if burnout looms? There is no panacea. It may seem that primal scream therapy and fistfuls of Xanax are the best recourse, but that just ain’t so, Maslach insists.

“The data on what works best isn’t definitive by any means,” she says, “but it appears that situational solutions work better than individual approaches. In other words, it’s probably better to change the values of the company than offer counseling to the employees.”