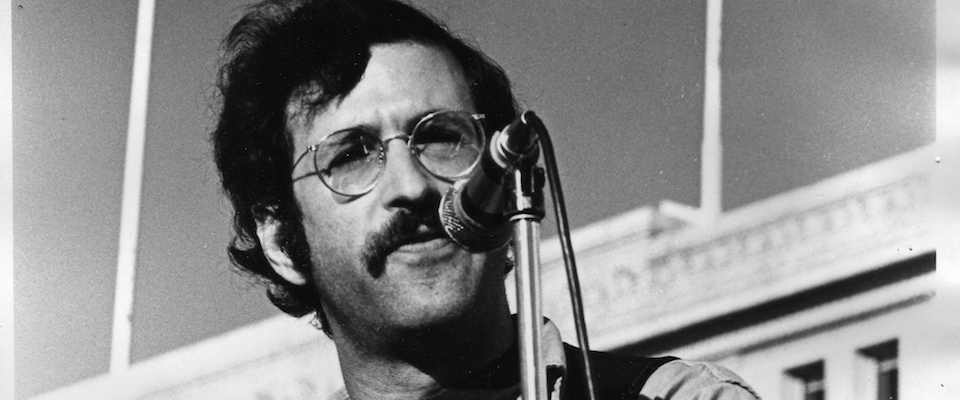

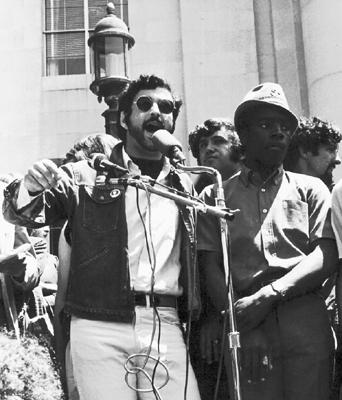

Five questions for Dan Siegel, famous as an articulate firebrand on the UC Berkeley campus during the heady 1960s. He is now 71 and is a civil rights attorney in Oakland. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In the spring of 1969, when you were studying law at Boalt Hall, a dispute arose over People’s Park. More than a year earlier, the university began clearing the park, which was just south of the campus, of old housing as part of a long-range redevelopment plan, but funding stalled and the park became a 2.8-acre junkpile of abandoned cars, garbage, mud and the remnants of partially demolished structures. In an act of civic pride and energy, an ad hoc group of students, local residents and merchants decided to turn the derelict land into a public park. But UC decided it was going to be a sports field and put a fence around the property. Things were at a benign standstill on the morning of May 15, when Gov. Ronald Reagan dispatched the National Guard. Ultimately, one man was shot to death (by police) and thousands protested while Alameda County sheriff’s deputies with shotguns fired into the crowd. You were at the center of it all, even to the extent of sparking the historic march from Sproul Plaza down three blocks to People’s Park. Tell us about that day and how you feel about it nearly 50 years later.

At the time, I was a second-year law student and was president-elect of ASUC [Associated Students University of California].That vacant lot had been repurposed by the community as a park and it was a very pleasant and constructive locus of activity. They had filled in the ruts, put up playground equipment, and everybody seemed to be having a good time. I couldn’t understand why it made the university people so uptight. That day, there was going to be a rally at Sproul Plaza – indeed, there was a rally every day. I went there and a student I knew said, “Dan, you’re the president-elect [of ASUC]. You should speak. So I got up there around 12:30 p.m. and I said a lot of things about how disturbing it was that the university was taking over the park. I believe what I said then was, “let’s go down there and take the park.” What happened next was very surprising: the police turned off the sound equipment. There were a couple of thousand people drifting around and we started walking toward People’s Park. I think the demonstration was appropriate. The people had a right to be angry.

Given the tug-of-war over the park, what was at stake that day?

The most important issue was whether students and other members of the campus community had the right to use University of California property for free expression and reasonable activity. It was one in a series of disputes between students and the UC administration—the Free Speech Movement, the Third World Strike, whether to hire professors of color, students pledging to resist the draft.

What, if anything, did this have to do with free speech and the Free Speech Movement?

It had to do with the issue of student self-determination, with expressive behavior, not political speech. We wanted to express ourselves by creating a park, for a practical purpose. The student movement in the 1960s was a political movement that had a strong cultural basis to it. In the Bay Area, it was joined to the youth movement that stressed sex, drugs and rock and roll, the kind of hippie culture that flourished in the Bay Area. This was a precursor to today’s issues of urban farming and community gardens. People looked at it in that way. Free speech in a broader sense means the right of the community to make decisions on how land is to be used going forward. When you look at the Free Speech Movement —and I felt this acutely when I was at Cal —our efforts to express ourselves about Vietnam got diverted to fighting UC about the use of university property and People’s Park was another chapter of that.

Earlier this year, speaking events on the Cal campus by two conservative figures, Milo Yiannopoulos and Ann Coulter, were canceled after university officials, in the face of demonstrations, said they could not guarantee that the speeches would be safe and peaceful. How do you contrast the People’s Park days with this recent controversy over whether conservative figures should be invited to speak at Cal?

I don’t know if there’s any connection. The fact that some conservatives and some Republicans have decided to make Berkeley a testing ground for their political initiatives seems really contrived. It seems like people from outside Berkeley are using Berkeley to push an agenda. What was going on around People’s Park legitimately flowed from what was taking place in the Berkeley community. It really came from the authentic student movement of the time.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times 11 years ago, you said People’s Park “has now become this somewhat forlorn urban park… It’s a place that no longer reflects the will for independence of the campus community. I think today if the university turned off its Wi-Fi, they’d get bigger demonstrations than they would for People’s Park.” Do you think that quote applies to the park’s condition today and, if so, where is the park today? What are the lessons to be learned from People’s Park?

I feel the same way as I did 11 years ago. The park is a gathering for people who live in that place. It’s a place for the homeless to gather. There’s open drug use. As for the lessons to be gained from all this, to be provocative, I’ll paraphrase Mao (Zedong) and say that political power grows from the barrel of a gun. Political power in the student movement flowed from the number of people we were able to mobilize. The university backed down from plans to build a soccer field at People’s Park. When I [look at the period of] 1964 to 1970 and see that in the spring of 1970 we could use any campus facility we wanted to use, that was because of support from students. It was remarkable, in the three years I was there, to have campus demonstrations of 3,000 or 4,000 students. Thousands of people in the Greek Theater or Edwards Gymnasium. It showed our support. And the outrage.