Iris Yamashita has always loved fiction writing, but it was a winding road to her first novel, City Under One Roof (Berkley/Penguin, January 2023). As she explained, “I have Asian parents and they really expected me to be a doctor or engineer or something. Writing was okay as a hobby, but not okay as my main focus.” So she studied engineering at Berkeley with a minor in creative writing. When she decided to take writing seriously, she turned to screenplays after struggling to complete a novel. She found success with her script for Clint Eastwood’s 2006 war drama Letters From Iwo Jima, which was nominated for four Oscars, including for Best Original Screenplay. That achievement motivated her to finally finish a novel.

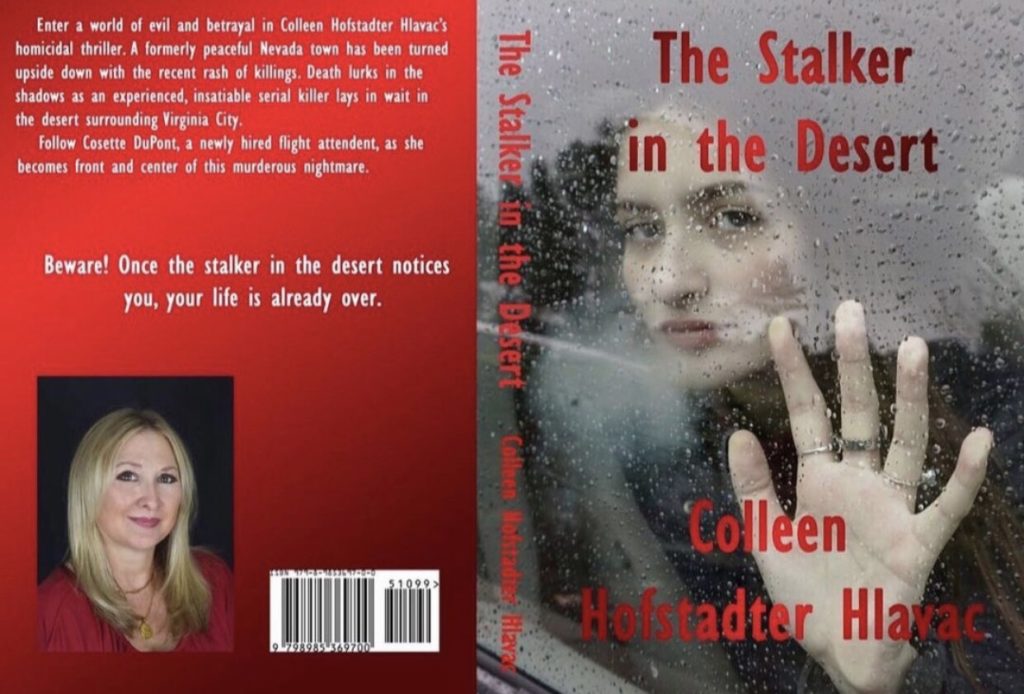

The result, City Under One Roof, is a thrilling murder mystery set in a tiny town in Alaska where everyone lives in a single apartment building. California magazine sat down with her to discuss a strange Alaskan town, how she became a writer, and the best advice she got from a mentor.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your setting is based on a real town: Whittier, Alaska. I didn’t realize that at first. Reading the book, I was scared. Now that I know it’s a real place, I’m terrified. Have you been there?

I found out about this place through a documentary I saw more than 20 years ago. Back then, the only way in was by train. I talked to someone who had lived there for a long time, and they said that in the old days, you could drive your car there, and then your car had to go on the train. That’s how you got in. So it was even more isolated than it is now. The people who live there were actually kind of upset that they made a road that cars could drive on because they wanted to stay isolated.

I went to visit after the road had opened up. And it’s not quite as scary as I make it out to be in the book, although I went there in the summer, so there’s beautiful scenery and the people seem pretty nice. But I’m sure if you were there during the winter, it’d be kind of scary because of the wind, how it howls and all of that. That’s all true. So I don’t know if I’d want to be there during the winter. But it is a fun place. There are a lot of strange things, going there in person, but I don’t think the people are as scary as I make them out to be. Which is why I changed the name of the city.

Did the town inspire you to write the book?

Definitely. It was always in the back of my mind after seeing that documentary and just going, “Wow, that is such a weird but cool town. That has to be the setting of some kind of story.” It took me a long time to think, “Oh, it’ll be a mystery. There’ll be a dead body and you’re going to be trapped there.” Then as I was doing research, I saw videos of the tunnel that you drive through to get there, which is two and a half miles long. So it’s a long drive through this tunnel, which is very craggy, like a mine. It made me feel like I was falling through a hole. And the idea of Alice in Wonderland, of falling through a hole and ending up in this really strange place full of really strange characters, is what got me going.

So I have three voices. The protagonist is the detective Cara Kennedy. She’s like Alice being thrust through the hole into this weird place, Wonderland, and then gets trapped there. Another voice is Amy Lin, and she is, in my mind, the white rabbit that Alice chases to get clues. And then there’s Lonnie Mercer, the moose lady, who is like the Mad Hatter because she wears colored berets every day and has a strange mental disability, one that I thought of as a mixture of schizophrenia and OCD coming from trauma. If you look deeper into the book, you’ll see a number of other Alice in Wonderland analogies that I don’t know if anyone will catch, but it was a fun process to think of it in that way.

What are some of the major themes in the book?

First, there’s community and isolation. I lived for a while on Guam, which is a tiny island that feels isolated and like you’re stuck there without much to do. The boredom and the feeling that you want to get out—I think that’s present in Amy’s story. After COVID, I think we can all relate to the feeling of being isolated. I don’t think I could live [in Whittier] myself, but I read a review from someone who thought this community was amazing and said they’re actually looking for real estate there now.

You have this love-hate relationship with your community. But I do think that at the end of the day, people are going to rally together. In a way, you have to depend on them because you’re so isolated and in a remote area. I read somewhere, and I don’t know if this is true, that it feels like everybody [in Whittier] has to wear multiple hats. Somebody has to volunteer to deliver the paper… Everybody has to step up in this community; otherwise, it can’t function.

The other theme that I touched on is violence against women in Alaska. Something I was really surprised to hear when I was doing my research initially is that when there wasn’t a way for cars to get [to Whittier], it became a haven for women who had been abused and would tell the train conductor, “Don’t let my ex in.” Then, after doing more research, I found out that Alaska is the most dangerous state for women. A huge percentage [of women in Alaska]—like 60 percent—have suffered from domestic or sexual violence. That was really shocking.

Switching gears, when did you first discover your love of writing? Do you remember the first story you ever wrote?

I’ve always loved writing. I remember somebody had gifted me an empty diary, and I thought I was supposed to write about a make-believe me. I would write these stories where I would use “I,” but they would be set in a different era.

I read that you also studied virtual reality at the University of Tokyo.

It started at Berkeley. I was doing my research papers with Dr. Lawrence Stark. He was a professor who had a hand in a lot of different things. He was in the optometry division, but he was also a mechanical engineering professor and had a degree in electrical engineering. He was a true renaissance man. He was an artist and he knew about history. He also encouraged my writing. He had a visiting professor who was in virtual reality. Then I went to Japan because he had a research exchange program. So I was able to go to the University of Tokyo and dabble in virtual reality. It was fun. It was definitely interesting. But at the time, I didn’t see many uses for it other than video games.

As an alumni magazine, we have to ask: Does anything from your time at Berkeley inform your writing?

While I was at Berkeley, there was an engineering and arts magazine, and I submitted something and it was published, which was cool. And again, [Dr. Stark] encouraged me to be more aware of [the fact that] there’s science, but there’s also art, and it will improve your mind and your life to be interested in a lot of different things. In that respect, I was really lucky to have such an amazing professor. And I still remember, too, I was talking to him about writing my thesis, and I was like, “I’m much better at writing fiction than academic papers.” And he said, “Oh, don’t worry, it’s all the same. We’re just doing fiction.”

Another thing he said that I would even tell my students when I later became a writing instructor was his story about these two scientific papers that he had written as a grad student. He had submitted paper A to journal A and then paper B to journal B, and they both were rejected. So he switched the papers: He sent paper B to journal A and paper A to journal B, and they both got accepted. It’s the moral that everything is subjective and to not take rejections so hard. You will get rejected over and over and over in the writing world. That’s just part of it.

What’s different about writing a novel versus a screenplay?

I thought I was going to write a novel first. I was taking classes about writing novels, but I could never finish one. I would get started and quit midway. I started taking UCLA extension classes in screenwriting at night while working full time. After I finished a screenplay, I started entering it in contests and it ended up winning first place in a contest where a Creative Artists Agency agent was a judge. She then offered to represent me.

Screenwriting just seemed so much easier because it’s only 100 pages and there’s more white space. It’s not as torturous. I found that I could actually finish screenplays. Then I made a career out of it. I got a lot of tools along the way of learning how to outline a screenplay, and it made me realize that I couldn’t finish a novel because I never properly went through the outline process and figured out how to actually finish the story.

But they are two completely different types of writing. I feel like a screenplay is easier to write and complete overall, but very, very hard to get made. Whereas the book is much more torturous in the writing process, but maybe slightly easier to get published. It doesn’t require as many people to get something published, and it doesn’t require as much money to produce either. There’s something there for people to see that you were actually working on, unlike with a screenplay, where you can work and work and work and no one will ever see the finished product. I was making a good living writing screenplays, but no one would see the finished product because to get to that final produced state takes too many people and too much money.

Why a thriller for your first novel?

I was trying to get my foot into the television world because film, unless it’s a superhero mega-blockbuster, is kind of dead now. I think it was with Jane Campion’s miniseries Top of the Lake that I just went, “Wow, this is so interesting. I want to do something along that line, where it’s a mystery in a contained place with interesting characters.” So I actually wrote the pilot of my story before it became a novel. It was just going to be a sample to get my foot in the door. And producers really liked it. Wherever we sent it, they were encouraging me to sell it as a series. So I had to think of the whole season and beyond. Ultimately, we didn’t sell the series because I hadn’t written the book yet, so I didn’t have [the intellectual property] and there was no built-in audience. But since I’d done all this work, I thought, “I can write the book.”

Could a TV series be in the future?

That would be great. Now that there will be IP, we can try it. We might be able to make a movie or a series of movies. Those are possibilities for sure.

It’s harder in streaming. With books, you can have a gazillion mysteries with the female lead in a cold place. But when you go to streaming or television, the execs are like, “Oh, we already have a woman detective story in a cold place.” A lot of them won’t even look at the script because of the programming that they already have. It’s a lot of luck and timing.