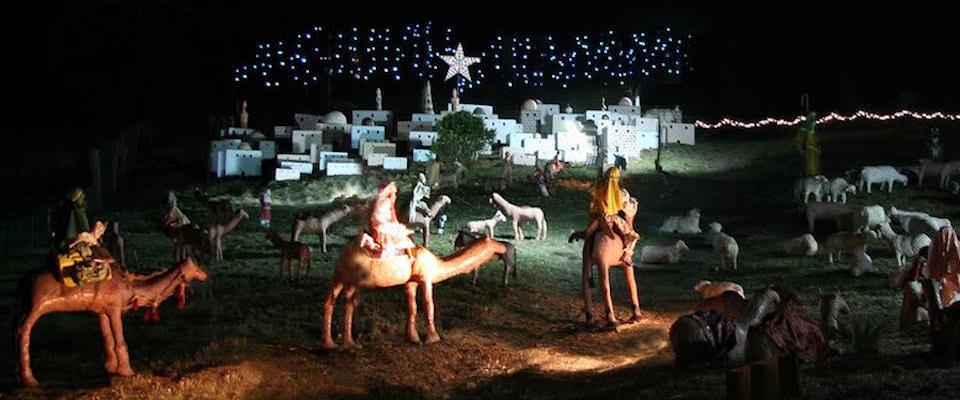

On Saturday morning, El Cerrito firefighters working on their own time will haul scores of handmade stucco and plaster statues uphill from their storage site to the corner of Moeser and Seaview. There, Boy Scouts from Troop 104 will arrange them to create a massive tableau of Bethlehem: Wise Men, goats, donkeys, camels, camel drivers, more than 60 sheep tended by shepherds and sheep dogs, village people, and the village itself, including 110 hand-painted buildings, minarets and domes.

“We’ve already been working for the last two weeks, putting the lights, sound equipment, and security cameras up and covering the ground with mulch so everything is firm and ready to receive the figures,” says El Cerrito Mayor Greg Lyman. “Depending on how much rain we get on Thursday, I might go out there on Friday and weed whack the site one more time.”

And for the next two weeks, as they have for more than six decades, thousands of visitors will come from all over the Bay Area every night to view the display until December 27, when the statues return to storage for another year.

It’s a tradition that goes back to 1949, when the neighbors of Sundar Shadi awoke on Christmas morning to find a large sculpture of a star he had created in the yard next to his home on Arlington Boulevard.

He kept adding figures—crafted out of coat hangers, juice bottles, coffee tins, stucco, plaster of Paris and chicken wire—until they numbered in the hundreds .

The next year, he added some sheep and shepherds. The year after that, camels and donkeys. And he kept adding figures year after year—all lovingly hand-crafted out of common household items such as coat hangers, juice bottles, coffee and cookie tins, stucco, plaster of Paris and chicken wire—until they numbered in the hundreds. The buildings were crafted from milk cartons, the camels’ manes made from rope, reins fashioned from old leather belts. Shadi’s wife, Dorothy, created weatherproof clothes for the human figures out of old oil tablecloths and plastic shower curtains.

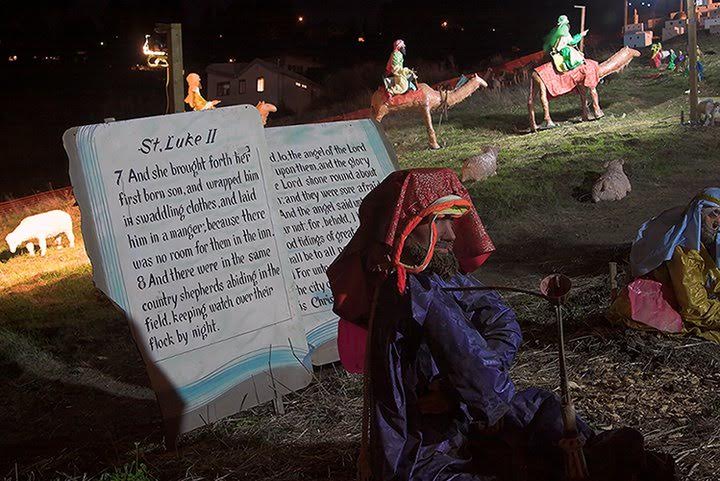

The final additions were a giant angel to watch over everything and two huge tablets with a Bible verse, Luke 2: 7-11 (the same verse that Linus famously recites in “A Charlie Brown Christmas”) – “And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn. And there were in the same country shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord.”

Curiously, Shadi was not a Christian himself. “My father was a Sikh who came from the Punjab, a place where ISIS is very strong now,” says his youngest daughter, Vera. “He suffered a lot of religious persecution in India—one of his brothers was killed during a violent uprising—and his family had to flee to what is now Pakistan. He was very grateful for the tolerance he found in America, and he always said he wanted to create a spot of peace because he came from a war-torn area. He really didn’t know anything about the Christmas story when he came here. My mother taught it to him. But he wanted a display that would reflect everyone’s beliefs, no matter what their religion.”

“I think it was his way of saying ‘I love you’ to his neighbors in a language we could all understand,” adds former Mayor Jane Bartke.

(There are so many mayors in this story, you might begin to wonder, “Is there anyone in El Cerrito who hasn’t been mayor?” And the answer is: Not many. The mayor’s office rotates every year among city council members.)

Shadi didn’t know much about making sculptures, either. “He went to the library to research stucco and plaster-making techniques and studied animal pictures on Christmas cards,” says his eldest daughter, Zilpha. “He started making sheep. More animals followed. The first head of a person he made looked so much like a friend of his, he decided not to use it. The heads were put on the front steps of our house to dry. The first one was put on the top step. Soon heads were down on all of the steps.

Sundar Shadi came to America in 1921 to study horticulture at Cal, where he got his bachelor’s degree in 1926 and his master’s three years later. He met his future wife, Dorothy Clarke, at the campus’s International House.

She was as remarkable in her own way as he was. A 1929 graduate of UCLA, she received her master’s in Spanish and French from UC Berkeley the following year and her Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literature in 1934. After taking several years off to raise their three daughters—Zilpha, Ramona and Vera—she returned to Cal in 1948 and climbed the academic ladder to become a professor of Spanish, Assistant Dean of the College of Letters and Sciences, and a leading authority on Hispanic literature. She was also awarded the Berkeley Citation for “services to the university above and beyond the call of duty.” Though her students and professional colleagues knew her as Mrs. Shadi, all her academic publications were published under her maiden name, Dorothy Clotelle Clarke.

“Dorothy was known as The Cookie Lady in our neighborhood,” adds Jane Bartke. “All the kids in the neighborhood knew they could go to her back door and get cookies.”

In 1948, Sundar Shadi became an American citizen. Despite the fact that he encountered less discrimination here than back in India, there was still enough prejudice to deny him work in his chosen profession.

Undaunted, he got a job pumping gas in a gas station. He worked hard and saved his money, and within a couple of years he had enough to buy the station. Then he bought another one. And another. And another. Then he branched out to other properties, including a lot on the corner of Shattuck and University in Berkeley, which he leased to a fledgling new hamburger chain called McDonald’s.

But he never gave up his interest in horticulture, publishing many scholarly articles and being elected to several professional societies, including Phi Sigma Biological Society and the Society of Subtropical Horticulturalists.

By 1949 he had amassed enough money to retire, and that’s when his true calling began. That Christmas the first star appeared on the hillside next to his home, and the rest is history.

“Dorothy wanted him to have activities, as all good wives want their husbands to do when they retire so they won’t drive us crazy,” says Dee Amaden, one of the next generation of volunteers who are keeping the tradition alive.

“To most people around here, Mr. Shadi was Christmas. The holiday display was his gift to his neighbors and his city, which he loved so much.”

His wife died in 1992, but Sundar kept going until failing eyesight and hearing forced him to give up the annual display four years later. He died in 2002, just one month short of his 102nd birthday. Former Mayor Jean Siri spoke for the whole city when she said, “I feel a great vacancy. First it was my tradition, then my kids’ tradition, and now my grandchildren’s tradition.”

But then something wonderful happened. The people of El Cerrito refused to let his legacy die with him. Under the leadership of Jane Bartke, who was president of Soroptimists International of El Cerrito, the Soroptimists formed the nonprofit El Cerrito Community Foundation, which assumed ownership of the Shadi sculptures from his family and agreed to revive the annual holiday display.

Bartke and her husband Rich, a friend of Shadi’s for more than 35 years, lined up the firefighters and local volunteers to move the display to its new location at the corner of Moeser and Seaview, where PG&E owns property that it agreed to let the Community Foundation use every December.

Many of the sculptures were in deteriorating condition by then, especially two large camels with eight broken legs and a broken neck between them. So Matt Houser, a senior at El Cerrito High and an Eagle Scout, repaired the two camels with help from his younger brothers, Ethan and Zach, who went on to become Eagle Scouts themselves. “I’d been seeing the display every year since I was a little kid, so I thought it would be a cool thing to do,” says Matt. “We created an inner skeleton with steel and rebar, so the weight would not be supported by the chicken wire or the plaster. We put a steel plate in the abdomen area and then welded rebar from that plate down the legs and up the neck. It’s similar to the way the Statue of Liberty is constructed.”

That tradition is being continued this year by Alexander Bjeldanes and Jared Long, who have rebuilt several houses, domes and minarets as their Eagle Scout Project.

Over the years the display has garnered many awards, including the San Francisco Examiner Outdoor Lighting Contest, Northern California Outdoor Christmas Tree Award Association Grand Award, and the General Electric National Outdoor Christmas Decoration Contest, as well as being featured in Sunset Magazine.

Ideal viewing hours are between 5 and 10 p.m., when the village is illuminated exactly as Shadi intended. “One of the little tricks he had was to tilt the buildings slightly toward the viewer so you can just make out the top of the roofs,” Lyman says. “That was the perspective he wanted.”

Volunteer docents, called Shepherds, will be on hand to talk with visitors and provide more insight into Shadi and his amazing creation, under the guidance of Lead Shepherd Donna Houser, a fellow Cal alum whose day job is senior director of facilities and hospitality at Alumni House. In addition, the display will feature live concerts of traditional Christmas music by the Contra Costa Chorale at 7 p.m. on December 15, the Unitarian Choir at 7 p.m. on December 17, and handbell musicians Larry and Carla Sue at 7 p.m. on December 19 and 23 (Editor’s note: Click here for information on Shadi Holiday Display events taking place in 2022).

There are two additions to the display this year. One is a new figurine: a life-sized statue of Shadi himself, modeled after a picture of him in an old newspaper clip. The other is an improved security system.”

“Last year, after the lights were turned off, a vehicle showed up and two people got out and stole the angel’s head and an entire shepherd,” says Lyman. “Unfortunately, the video turned out too grainy to identify them. We’ve replaced the head and the shepherd, but we’ve also upgraded the video cameras to get much better definition. If anyone tries it again this year, they’ll get caught.”

Everyone associated with the project, from the Bartkes on down, is contributing services free of charge. But there are always incidental expenses to be met, including electricity, insurance, light bulbs, electrical cords and storage. And, of course, more volunteers are always needed.

A website for the Shadi display offers links for people wishing to volunteer or donate: for example, sponsors can “adopt” individual figures such as one of the Wise Men, camel included ($500) or the big blue star ($200). The sheep are a steal at $25, probably because there are so many of them.

“To most people around here, Mr. Shadi was Christmas,” says Jane Bartke. “The holiday display was his gift to his neighbors and his city, which he loved so much. We’re going to keep that tradition going for at least another 60 years, and hopefully forever.”

(All display photos courtesy of the El Cerrito Community Foundation.)