It’s mid-July in Bad Doberan, a small town in Germany about two and a half hours north of Berlin. More than 2,000 music fans are present, and many, many of them are sporting Frank Zappa–style moustaches (including one young woman whose facial adornment is from a magic marker).

This is Zappanale, pronounced “zap-pa-nal-lah,” a weekend rock festival dedicated to the music of the late rock musician. Standing out among them is Jim Cohen, the show’s master of ceremonies, wearing a light-blue plaid jacket and a skinny black tie.

Cohen, who graduated from UC Berkeley in 1985 with a bachelor’s degree in linguistics, is a Frank Zappa interpreter. A resident of Germany since the late 1980s, he has been giving presentations about Zappa’s lyrics to German audiences for more than two decades. He is also a vital part of what could be the largest music festival in the world dedicated to a single rock musician.

To understand how this came to be, one has to understand Zappa. And Cohen.

Zappa, a Los Angeles resident who died from cancer in 1993, was both iconoclastic and amazingly productive. During a 25-year musical career, he put out more than 50 live and studio albums, ranging from rock to jazz to classical. He was famous for both his musical complexity—his backing bands rehearsed 40 hours per week—and his lyrics, which were at times sexual, sarcastic or satirical, but almost always hilarious. Today, his family continues to release material from his huge archives, and his fans remain as rabid as ever.

Zappa had always been big in Europe, especially in Soviet satellites (the late Vaclav Havel, leader of Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, was a huge fan). In a society where saying the wrong thing could get you in trouble with the Stasi, the German Democratic Republic’s secret police, Zappa songs like “Plastic People” and “Who Are the Brain Police” resonated with many young people. At least, it did for those who managed to hear them—albums from Zappa and other Western rock bands were illegal in most communist countries.

Zappanale, a play on the word biennale (an arts festival that happens every other year), began in 1990 in East Germany. The Iron Curtain had parted, but the two Germanys had not yet been reunified. In the north, some music fans wanted a party to celebrate.

They brought a flatbed truck to Bad Doberan, a quiet resort town a few miles south of the Baltic Sea. A sympathetic West German rock band drove across the border to play a concert, including some Zappa songs, and promoters followed it up with some old Zappa concert videos playing on Soviet-made televisions. The festival went until 4 a.m. and attracted about a hundred people.

“Although things were changing rapidly, it was still the DDR, and organizing and staging the event was pushing boundaries,” recalls Matthew Galaher of Portland, OR, who had mailed Zappa albums to East German fans in the 1980s, and later attended the first Zappanale. “There was a sense of adventure just in the fact that the event was happening.”

As for Cohen, the Santa Monica native has been a Zappa fan since he started listening to rock music. His obsession with the musician—Zappa fans are often obsessed—really took off after he began attending Berkeley and discovered Zappa’s three-record concept album, Joe’s Garage. He even saw Zappa in concert at Berkeley in 1984.

Cohen came to Berkeley to study astronomy. But after discovering that calculus didn’t agree with him, he switched to linguistics. He’d always liked learning new languages (he knows at least five today) and decided it would be fun to study the structure and history of language.

After graduation, he moved to Germany to earn a master’s degree in linguistics. In 1994, he gave his first talk on Zappa’s music. He got the idea after explaining the song “Bobby Brown” to a rather uptight German friend. The risqué song off the 1979 Zappa album Sheik Yerbouti, was a hit in Germany—but few people knew what the words actually meant. The friend was aghast when he learned that it described, in exquisite detail, the sexual misadventures of an archetypal college jock.

“He was so shocked,” recalls Cohen, “I decided ‘Hey, this must be good.’”

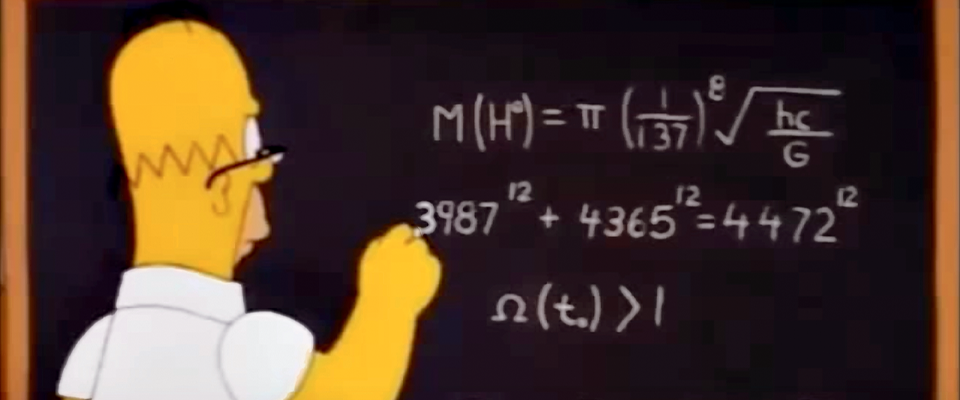

Cohen began doing 90-minute Zappa presentations in a local pub. Typically, he’d play about five Zappa songs, and then explain in German what all the obscure references meant. For instance, a number of songs off Zappa’s 1972 record Just Another Band from L.A. mention now-defunct Los Angeles businesses, The Tonight Show, Howard Johnson’s Motel, and other things that would be over the head of even the most well-informed German. In addition, many of his songs refer back to older songs, making a unified body of work the artist referred to as his “project/object.”

“Zappa’s lyrics are multi-leveled,” says Cohen, 53, who lives in Munich and works as a technical translator and teacher. “There’s always an easy message for people who simply listen to the words. If you take the time to analyze what he’s done, you can see he’s drawing comparisons and reminiscing. His unit of artistic creation was not the song, or the album—it was his life work.”

In 1999, Cohen gave his presentation at Zappanale for the first time. A year later, he became the show’s volunteer M.C.

“The Zappanale is a unique place and time,” he says. “I get to spend a week each year immersed in the kind of music that is essential to me. And that’s more than just Zappa—where else can you hear three days of [jazz musicians] George Duke and Jean-Luc Ponty, then turn around and hear Z3, a Hammond organ trio, jam Zappa’s music perfectly until four in the morning?”

Now in its 27th year, the festival has evolved into a four-day event, attracting bands from all over the world, including former Zappa band members and even several of Zappa’s siblings. This year, the festival begins July 15 and includes The Magic Band, playing the music of Zappa contemporary Captain Beefheart; and The Grandmothers, featuring members of Zappa’s original band, The Mothers of Invention. The festival is a big deal in this community—local leaders even erected a bust of Zappa at the entrance to town.

“The Question of ‘why Zappa’ is easy to answer,” says Zappanale spokesperson Thomas Weller. “His works have to be kept alive.”

Zappanale attracts fans from all over Europe, with a smattering of Americans. During the weekend, Cohen gets on stage after each performance to speak to the audience in a smooth, radio-friendly voice, in English and German. He also gives his Zappa lyric lectures in a smaller tent filled with couches, typically to an audience of around 80 people. During last year’s festival he helped translate a rap session with Ike Willis and other musicians who played on the Joe’s Garage album.

This year, 23 years after his death, Frank Zappa is back in the news. His widow, Gail, died last fall. His son, Dweezil, who continues to tour with a band playing his father’s music, is fighting another son, Amhet, over the rights to use Frank’s music. A documentary, Eat That Question: Frank Zappa in his Own Words, is being released this summer. Another documentary about the musician’s life, produced by actor Alex Winter, is also in the works. Winter, a lifelong Zappa fan, hopes to raise enough money to find a home for the thousands of hours of recordings that Zappa fastidiously archived in the studio below his house (which is now for sale).

For Cohen, now married with two young daughters, this year’s Zappanale will be yet another chance to catch up with old friends, enjoy the music and continue to help Germans understand the world of Frank Zappa.

“Coachella, all the big music festivals, are industry products. We come here to do Zappa,” says Cohen. “And to remind one another there are still a few people who know the difference between Hollywood and real music.”