There is raw, if cloaked, combat going on at UC Berkeley over the core of the campus: the University Library.

The turmoil is over the biggest change in information systems since the invention of movable type some 500 years ago. On one side of the battle line are the steely advocates for embracing what they firmly believe is the future of Internet-based information centers. They unabashedly acknowledge that means retreating from the shelves of books that have been libraries for millennia. On the other side are the passionately aggrieved fighters for preserving the ancient legacy of books, which they assert have lost none of their power and purpose—and likely never will.

Academia, of course, is no stranger to politics. There are plenty of aphorisms about how the fighting is more vicious because the stakes are so small, not to mention a now somewhat infamous essay by Stanley Fish—entitled “The Unbearable Ugliness of Volvos”—that is a hysterically sharp rebuke of insular, academic politics. But this is about the sancta sanctorum of the Academy—the holiest of holies—and few appear to be light-hearted about that kind of real estate.

The University of California library started in 1868 with 1,000 volumes. Today UC Berkeley’s libraries alone have more than than 11 million. (The University of California library system now has some 36 million volumes, exceeding the number in the Library of Congress.) This substantial investment is not just financial—it is understandably emotional. Consider a statement in the opening pages of the Report of the Commission on the Future of the UC Berkeley Library from last October: “There is simply no great University without a great library.”

For as long as anyone can remember, such a declaration had gone unchallenged. But then came along people such as Michael Eisen, a sparky professor of molecular and cell biology.

“Fifteen years from now you won’t need a library,” he says, his office cluttered with a 52-inch flat screen monitor, a collection of beer cans and a bike. The 46-year-old says “I’m not sure we’ll even have a one” when he’s 60. And he says he won’t miss it.

Eisen admits that in his graduate school days he enjoyed the bound science journals in the library. But now? “I haven’t been to the library to get a research article in 15 years.” Most of what he wants he grabs online.

As with many academics in the sciences, he is particularly torqued by the price of getting journal research. For example, the Brain Research journal has a subscription price of $19,952 a year. The Journal of Comparative Neurology is $35,489. His outrage at the cost of accessing such information led him to form the nonprofit Public Library of Science (PLOS), which has become the prime publisher of “open access journals”—a cause he champions in the Winter 2013 issue of California magazine.

Those who advocate saving the central stacks, in his view, are guilty of the “fetishism of print.”

Bearing in mind that the central image in the university’s seal is a book, one can stroll past the Campanile from Eisen’s modern Stanley Hall office, and in minutes be at the magnificent John Galen Howard edifice in the very heart of campus.“The University Library,” it declaims in chiseled Sierra granite above the portal. This is Doe Memorial Library, opened in 1911.

Reaching Margaretta Lovell’s office atop Doe requires taking the stairs past the part where they are well maintained, or taking the elevator that could be from the service entrance of a prewar garment factory. Either way, you’ll know you’re not at Stanford. The professor of art history is in an office that has fixtures from 1923, book cases from goodness knows when, and a view to the west that never gets old.

“I want to defend what is still useful,” she says.

In an internal memorandum she shared, Lovell noted “no other resource on campus is so central to the daily conduct of teaching, learning and research by every member of the academic community; when the library falters, the institution as a whole falters.” She mourns the loss of funding in the library, especially the 25 percent reductions in staff since 2007. “Librarians help scholars with knowledge they didn’t even know they needed,” she says. This has special application for Berkeley’s most important clientele: undergraduates, who, Lovell notes, really “don’t know what they don’t know.”

Many others with uniquely nuanced positions surround these dueling camps. And because it is Berkeley, there is a mountain of scholarship supporting each.

One celebrity academic whose name always comes up is Robert Darnton. Now the Harvard librarian, he tries to chart a middle course, writing scathing articles in the New York Review of Books about Google’s ongoing attempt to digitize books. But he also presses the point that the future is digital and everyone should get on board. “What could be more pragmatic than the designing of a system to link up millions of megabytes and deliver them to readers in the form of easily accessible texts?” Darton asks.

Another voice in the fray, writer Nicholson Baker, complains that libraries have systemically trashed America’s heritage by microfilming newspapers and sending the hard copies to recycling centers and garbage dumps. And he’s not just whining. Baker created the American Newspaper repository, now at Duke University. He does not contend that libraries serve people. He says they serve history. And he has taken particular aim at the San Francisco Public Library for its culling 200,000 books.

More relevant to the Berkeley ecosystem is Tom Leonard, a youthful 69 year old who used to teach the history of journalism and now is the university librarian.

Amid the turmoil about the future of the library, Leonard can be found in the middle. It does not feel like a demilitarized zone. He knows there are fears that the future will pass by Berkeley, and there are fears that the valuable past and present will be destroyed.

From his expansive ground floor office next to the Bancroft Library—which incidentally gets among the fewest visitors but, unlike some of the other lesser-used subject specialty libraries on campus, is not on anyone’s list for potential elimination—he gets a fine view of the Campanile. But he is quick to take an interested visitor on a march through the stacks.

“There are more libraries than McDonalds in the United States,” he says. “And I don’t mean libraries that are part of elementary schools. I mean libraries that have their own roofs.”

As an aside, he notes that one can’t get a job at a McDonalds without an online application. And one presumes many people who would apply for such jobs don’t have their own Chromebooks or iPads. Where would they go? To the library, of course.

Leonard makes one point, then another contrasting one, having been nurtured, no doubt, in the Hegelian tradition of the dialectic.

“There’s not the same demand for books wanted a generation back,” he says. But he also notes that there are up to 800,000 people a year visiting Doe and Moffitt—more than all Cal sports events.

He agrees that browsing is one of the great virtues of having open stacks. But he also agrees that good software allows browsers to do much the same with digitized collections.

He agrees with the university’s Report of the Commission on the Future of the UC Berkeley Library that there must be a restoration of library staff. But he also agrees with those who insist the new librarians must be capable of helping scholars search for such exotic topics as making a map with GIS data correlating to French Literature.

And he further agrees that students, whom he has observed to be “nocturnal,” should be able to order pizza to the engineering library at 2 a.m.—but hastens to add that ain’t gonna happen because it means cockroaches. Not to mention that the Kresge Engineering Library in the Bechtel Engineering center closes at 5 p.m.

But at the end of the day, Leonard says without a hint of qualification: “I don’t think it makes sense to organize a campus around shelves. It used to. Not anymore.”

The engineering library is a good example of what some see as the practical future of the UC Berkeley libraries. The engineering school overhauled it some two years ago, removing half the 300,000 books and making room for better places to lounge around. The number of visitors shot up dramatically.

The same sorts of numbers are seen at libraries around the state and the nation, which are refashioning themselves as “learning centers.”

That may sound like a new label pasted over the old label “library,” and in some ways it is true. And not. Learning centers feature airy open spaces rather than desks and tables. People are encouraged to talk (in low voices) and collaborate. Librarians don’t just help with finding texts, but have expertise is finding—and using—relational databases, video, podcasts, 3-D animations and more. In Bay Area suburbs such as Walnut Creek, Lafayette and San Jose, new libraries oriented to be more information centers than book shelves are attracting new crowds of young and old. San Jose, in fact, has put together a partnership between the city and San Jose State University.

At UC Berkeley, Moffitt Library has moved toward the learning center model, featuring a media center, cafe and what it bills as the busiest computer lab on campus, as well as a research repository.

And more is happening in other universities coast-to-coast. The University of British Columbia is now more a learning center than a traditional library. So is the new $100 million library at North Carolina State University, which features a gaming laboratory, 3D printers, and dozens of group study rooms with glass panels upon which people write mathematical formulas, poems and illustrations. (For example, if you are researching 17th Century London architecture, you can experience a virtual recreation of the churchyard in St. Paul’s cathedral in 1622 , when John Donne delivered his Gunpowder Plot sermon.)

The University of Chicago seems to have found a middle course and kept much of its print material, but has closed the stacks to browsing, instead using robots to get requested volumes.

The same could come to pass at Doe Library, where the once beautiful but earthquake-unsafe central stacks divided by glass floors is now a cavernous void in the building.

What could happen to the magnificent reading room in Doe?

It will almost certainly remain. The now rarely used collection of the Readers Guide to Periodical Literature—the bane and bromide of Baby Boomer undergraduates—will look venerable beneath the dust. As a destination, the still-crowded oaken tables of the reading room are the best testimony to the utility of this dignified center of scholarly calm.

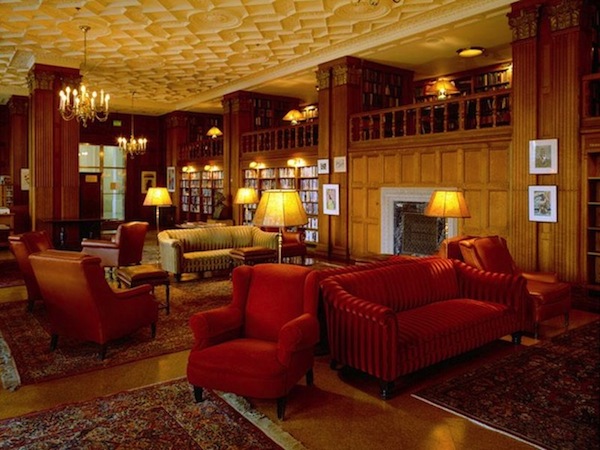

And the plush Morrison Library will remain a splendid refuge, presumably forever.

Alas, the Map Room is long gone, and will likely be devoted to what is today called Big Data. To the traditionalists, the Map Room—once an eccentric place on the ground floor of the Doe in which visitors could unscroll and peruse maps of all sorts, from the ancient to the up-to-date topographic—was just the sort of important endangered species the university should be preserving. To the change advocates, it was nice but a waste of prime real estate. It seems not that many used it.

Two years ago, the university conducted an email survey on library use. It was not a scientific polling of carefully selected sample populations, but nevertheless, only about a quarter of the undergraduates who responded said they used the library “a great deal.” On the other hand, 63 percent of graduate students and 78 percent of faculty said they did. Perhaps not surprisingly—mirroring the schism between Eisen and Lovell—the liberal arts crowd was significantly (60 percent) more likely to say it relied on the library than the engineering and science types (44 percent).

There is an abundance of literature and images and data about the past, present and future of the library. Some are dry. Some are beautiful. All will help inform the choices ahead, which will determine the destiny of the sancta sanctorum.