When her parents were in their 80s, sociolinguist Deborah Tannen took them to a therapist because, she says, “they seemed not to be enjoying each other.”

One problem was that her father, Eli Tannen, loved reminiscing about his childhood as part of a large extended family in the Hasidic Jewish community of Warsaw, Poland. By contrast, her mother, herself an immigrant from Belarus, had no interest in raking through the past.

As Tannen recalls it, “She told the therapist, ‘He keeps talking about dead people!’ The therapist said, ‘Can you take pleasure in the fact that he takes pleasure in it?’”

“No!” Tannen’s mother replied.

Fortunately, Tannen, 75, professor of linguistics at Georgetown University, felt differently. “I loved to listen,” she says, “and it was something that we shared.”

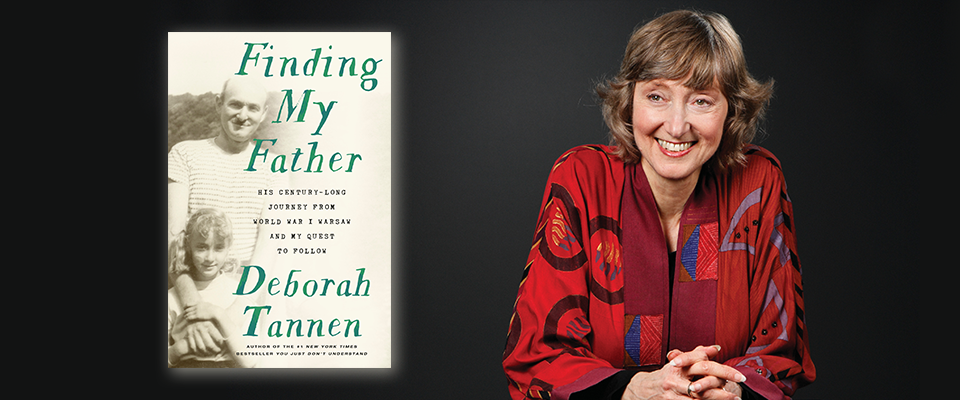

After earning her doctorate in linguistics from Berkeley in 1979, Tannen vaulted to celebrity with her 1990 book, You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. She traces her passion for language and writing to her father. Now his memories have seeded her latest book, her ninth for general audiences: Finding My Father: His Century-Long Journey from World War I Warsaw and My Quest to Follow (Random House).

Published in mid-September, the memoir, decades in the making, marks a departure for her. In volumes such as Talking from 9 to 5, I Only Say This Because I Love You, You’re Wearing THAT? and You Were Always Mom’s Favorite!, Tannen explored American work life, culture, and relationships through the prism of linguistics. While she has always drawn from her own experiences—her first academic paper was inspired by communications problems in her first marriage—Finding My Father, she says, is “completely different,” her most personal work to date.

Tannen says: “My bottom line is that my mother saved him—she gave him a life.”

The book touches on her mother, with whom her relationship, difficult for decades, eventually thawed. And it includes thumbnail biographies of some of her father’s relatives, including an aunt reputed to have been a lover of Albert Einstein and another prominent in Poland’s post-World War II Communist government. But, at its core, it traces Tannen’s efforts to understand her father’s life via his memories, his voluminous personal papers, and other sources. “He was a hoarder—and an organized one, thank goodness,” she says.

Tannen recounts that she missed her father growing up when he was often working. “The strongest presence I felt in the house was his absence,” she writes. But, after his retirement at 70, she captured their conversations on some 200 cassette tapes, too many to transcribe. “It was a bond between me and my father, the way that I could spend hours talking to him—and feel like I was doing my work,” she says. “I’m pretty workaholic, so I wouldn’t take time in the middle of the day chatting with my father if it wasn’t for a book.”

Eli Tannen’s life history, in his daughter’s view, was an amalgam of “bad luck and bad decisions.” Fatherless since childhood, he immigrated to New York at 11 with his mother and sister. He dropped out of school at 14 to become the family breadwinner—a decision that his mother discouraged. Tannen describes her grandmother in an interview as “extremely destructive, critical, demanding, verbally and physically abusive,” but says her father tried hard to please his mother.

He managed to obtain a law degree in his 20s without having attended college. But the Great Depression obliged him to detour into other jobs—including prison guard, alcohol tax inspector, and garment cutter. He didn’t start a law practice for almost 30 years.

His personal life had its shadows as well. He married a woman—Tannen’s mother—who pursued him relentlessly instead of a girlfriend who, in Tannen’s view, might have been more of a soulmate.

Tannen says that her father, who died in 2006 at 97, was eager for her to write about him. Above all, she says, he wanted her to preserve in print the vanished Warsaw of his youth, where, she says, he enjoyed “the warmth, the liveliness of so many aunts and uncles,” and felt a “sense of belonging and being part of a community.”

Those memories, including the family’s tribulations in a Poland impoverished by World War I, are reproduced in Finding My Father. But the trove of documents Eli Tannen left his daughter—most poignantly, his youthful journals and correspondence with the woman he romanced before his marriage—led Tannen in other intriguing directions.

One of the subjects he discussed “quite obsessively, in the spirit of an alternate life” was the woman Tannen pseudonymously calls Helen. “He always felt horribly guilty that he didn’t marry her,” Tannen says. She, herself, was charmed by Helen’s letters, which her father had kept through about 15 moves. “I fell in love with her,” she says. “She’s so lovely. She’s considerate. She’s thoughtful. She’s also a great writer, which is appealing to me.”

While her father was alive, with his backing, Tannen hired a private investigator in an unsuccessful attempt to locate Helen or her family. But, after her father’s death, she decided against following up on a possible lead. “I don’t know—if she has kids—if they would want to know,” Tannen says.

Tannen had always wondered whether her mother, who was the sister of her father’s friend and worked for a time in the same office, had manipulated her father into marriage through tears and illness. But the journals, which mentioned her far more than Helen, complicated Tannen’s perspective. “She was ubiquitous in his life,” Tannen says. In the book, she writes: “Sending a bon voyage gift to his mother, reading his mother’s postcard—my mother is always there.”

Their premarital sexual involvement was another factor. Though his relationship with Helen appeared to be more romantic, her father had resisted consummating it—primarily, it seemed, because he was convinced that Helen was a virgin. The irony was that she was not. It’s all very convoluted and astonishingly intimate.

Both women “gambled with virginity,” Tannen writes. “They just played the sex card differently. Helen hid the fact that she wasn’t a virgin. My mother wasn’t a virgin either, but she didn’t hide it; she used it. My mother’s gamble was the one that paid off.”

In convincing her father to marry, a move he had long resisted, Tannen says: “My bottom line is that my mother saved him—she gave him a life.” Otherwise, Tannen suggests, in thrall to his own mother’s needs, he might not have married at all. In the end, despite their problems, Tannen’s parents “were devoted to each other.” At one point, late in life, Tannen observes in the book: “They’re holding hands across their wheelchairs. They always hold hands.”

Tannen says Finding My Father was the most difficult book she has ever written. “The biggest challenge to me was how to manage so much material,” she says, as well as “not knowing how to structure the book.” In the early 1990s, she wrote a one-act play based on a trip to Poland with her parents. In 2012, six years after her father’s death, she finally started piecing together a first draft of the memoir.

During the project, she gained “an even greater appreciation for how hard he had worked and what he had sacrificed.” She also saw more clearly what she owed him. “I always knew that my writing and my interest in words and language came from my father,” she says. But, in finding letters she had typed to him as early as age 7, she saw “that writing was my path to him from early on … a way to connect with him.”

From her father, too, Tannen says, she inherited “a tendency to regret.” On the other hand, she is grateful that her parents’ longevity allowed them to witness her eventual success. “It was very satisfying that my parents lived to be so old”—her mother died at 93—“that they were able to enjoy that. That really was wonderful,” Tannen says.

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, has written for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, Slate, and other publications. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.