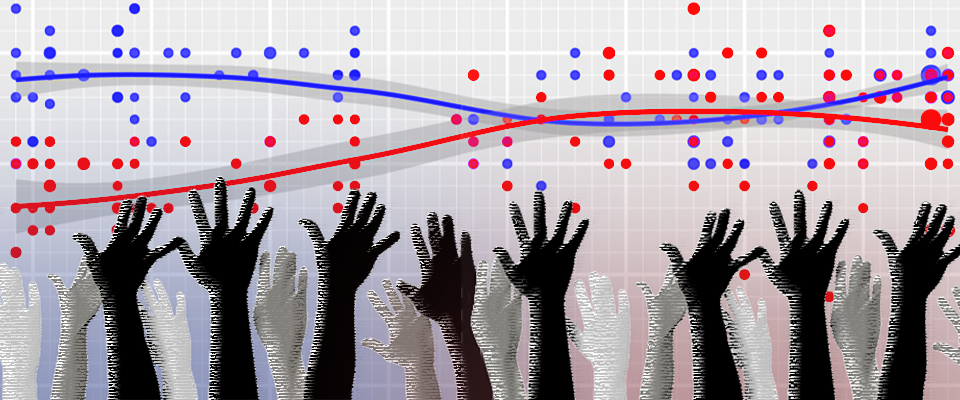

Last week Hillary Clinton was tied with Donald Trump for broad discontent among voters in a New York Times tracking poll. This week in the race for the presidency, Hillary beats Trump by five points according to a CNN poll. And a couple of weeks ago, a Rasmussen poll had Trump ahead by a couple of ticks. And this isn’t anomalous. The polls seem to be jumping around like caffeinated jackrabbits.

True, a certain degree of variation is standard for polls, but they seem particularly confusing this year. So in the age of social media and ubiquitous connectivity (and Pokemon Go) have polls—particularly tracking polls—gone from moderately useful indicators of voter sentiment to pseudoscientific exercises as worthless as phrenology?

Have polls, in short, lost their mojo?

Not really, says Laura Stoker, a Berkeley associate professor of political science whose research specialties include national elections and public policy. Polls are always volatile, Stoker maintains, and if they seem more chaotic during this election cycle, it may be due more to perception than reality. After all, everything seems more chaotic this election cycle.

Still, polls do vary widely, and that’s largely because there’s a lot of diversity in the way they’re conducted, says Stoker, who is writing a paper on survey research.

“We expect variation across surveys due to variations in sample size, differences in the way the samples are constructed, and varying voter response rates,” says Stoker.

A particularly critical component in polling—reasonably accurate polling, at least—is something called the “likely voter algorithm.”

“If you’re doing a poll in, say, California, you don’t want to survey the entire population,” Stoker says. “In fact, you don’t even necessarily want to focus on people who are simply eligible to vote, because only a small percentage of them will actually vote. So you want to target people who are not only eligible, but are likely to vote. That means you have to guess who are the likely voters, and base your polling preferences on that.”

To identify likely voters, pollsters develop algorithms to help winnow the herd. These algorithms vary widely, says, Stoker. Some are based on probability (i.e., random selection). Some rely on “opt-out” sampling: potential voters who haven’t offered to be part of a poll but are contacted anyway. Others are “opt-in”: respondents who have been recruited for participation in a survey. For the most part, says Stoker, tracking polls are probability-based, but some are opt-in. The best—Gallup and Pew, for example—work hard to know who is who among demographic groups.

“It’s a significant challenge to identify likely voters,” says Stoker. “Voter turn-out in the United States is low, and people who vote tend to respond differently to surveys than people who don’t vote. So the likely voter algorithms try to compensate for that using different weighting schemes, adjusted for both ‘politically interested’ and ‘not politically interested.’”

Adding to the conundrum of widely disparate polls is the fact that “survey companies have different ways of doing their work, and many of their tools, including likely voter algorithms, are proprietary,” says Stoker. “In many cases, we don’t know how they’re doing what they do. They’re in the business of being correct, so they don’t want to give away their secrets.”

Moreover, as with most things, you get what you pay for when it comes to polling.

“The best samples are usually the most expensive to obtain,” says Stoker. “They invariably involve face-to-face interviews. That’s a process that takes time, which is why it isn’t done for tracking polls.”

So how can you determine which surveys are the most accurate? That’s fairly easy: Don’t rely on individual polls. The best polls are meta-polls, analyses put together by polling data aggregators like FiveThirtyEight, the company founded by legendary pollster Nate Silver.

“FiveThirtyEight and a couple of other sites consider virtually all the polls,” says Stoker, “and they’re deeply attentive to variation and quality. So instead of an ordinary journalist or citizen evaluating polling results, you now have a very elaborate and objective statistical enterprise, and that’s a good thing.”

That said, the current shifting poll numbers may simply reflect high negatives for both presumptive candidates and the likelihood that voter opinions have not yet fully congealed on all issues. Moreover, it’s axiomatic in the polling biz that polls become more reliable the closer we get to Election Day.

“You have to keep in mind the particular moment we’re in,” says Stoker. “We haven’t even finished with the conventions yet. Right now, we’re seeing a lot of ‘no opinion’ on polling questions. That’s going to diminish through the summer as voters make up their minds on the issues. And we should expect to see turnarounds and shifts. Events—campaign bumps, convention bumps, national or international crises—matter. Typically, things firm up in the month before the convention.”

Still, while late polls are likely to reflect final outcomes far more accurately than early polls, no polls are foolproof. There are no guarantees in the polling industry, and for good reason: Surveys are upended with some regularity.

“Just look at the Brexit vote,” says Stoker. “Almost all the surveys got it wrong.”