The reference librarian slid the archival container across the counter.

“This looks like a fun box to look through,” he said. I smiled behind my face mask.

For several years COVID had shuttered archives everywhere and I was happy to be back at UC Berkeley’s elegant Bancroft Library where researchers ascend a grand marble staircase to reach the special collections on the second floor.

I carried the box back to my assigned place and very carefully leafed through the small, worn diaries, using the provided foam wedges and weighted string to protect the spines as I turned the delicate pages.

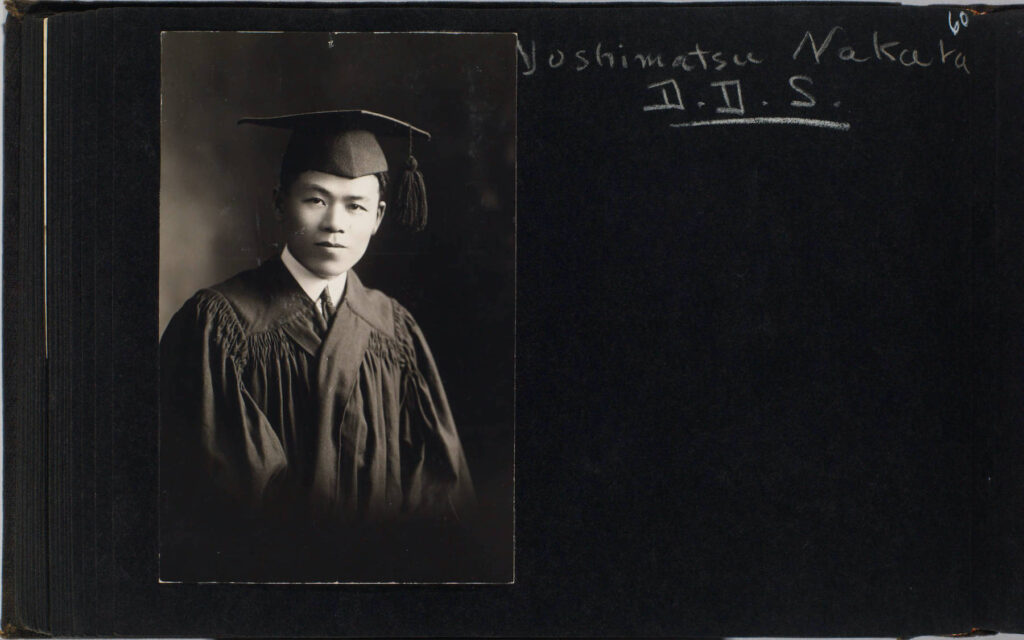

The journals belonged to Yoshimatsu Nakata, longtime valet to author Jack London, arguably Cal’s most famous dropout. One of the journals was from 1909, the other 1914. A few of the entries were written in English, but the majority were in Japanese, a language I neither read nor speak. I spent the rest of the afternoon scanning each page with my phone.

Nakata is a primary character in my book-in-progress, a place-based biography about London’s formative and lifelong relationship with the San Francisco Bay. My hope is that Nakata’s 1914 diary will help tell the story of London’s last, four-month cruise on the San Francisco Bay less than two years before his death.

I intended to hire someone to translate the diaries into English but immediately ran into a snag. After I sent a single-day’s entry to friends in Fukuoka, Japan, to get a sense of the content, they reported back that they could only read about a quarter of it. Thinking an older person might better understand, they enlisted the help of my friend’s mother. She couldn’t read it either. Even a group of retirees at their local library, who adapted old Japanese to new, had trouble.

To gain perspective, I contacted H. Mack Horton, professor of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Cal. “The problem, I’m guessing, is not the language per se but the writing system,” he replied by email. He asked to see an entry and his response gave me hope. “It’s simply vernacular Japanese from more than a century ago but written with obsolete characters in cursive. The grammar itself is largely modern, with some old-fashioned elements.”

With the help of colleagues and Japanese friends, I found several professors in Japan who were willing to help. I learned that the history of Japanese language and writing styles is complex and that the professors would first have to adapt the characters into modern Japanese before it could be translated into English. Professors Nagako Muto and Takaharu Mori from the International University of Kagoshima are adapting and translating a section of the 1914 diary for me, with assistance from graduate students Chisato Kubota and Sato Shirakubo. Professor Mami Fujiwara at Yamaguchi University is working on portions of the 1909 diary.

Yoshimatsu Nakata was Jack London’s right-hand-man for eight years, at the height of the novelist’s prolific career. At the turn of the last century London was one of the most widely read writers in the world. In 1897, already a committed socialist, London dropped out of the University of California after one semester to seek his fortune in the Klondike. He didn’t find gold but did return with vivid impressions that he turned into stories that became bestsellers, including such adventure classics as The Call of the Wild and White Fang.

In 1907, seeking more adventure, London sailed to Hawaii on the Snark, a 45-foot yacht that he had built to his own specifications for an around-the-world journey. In Hilo, Hawaii, he hired Nakata as cabin boy.

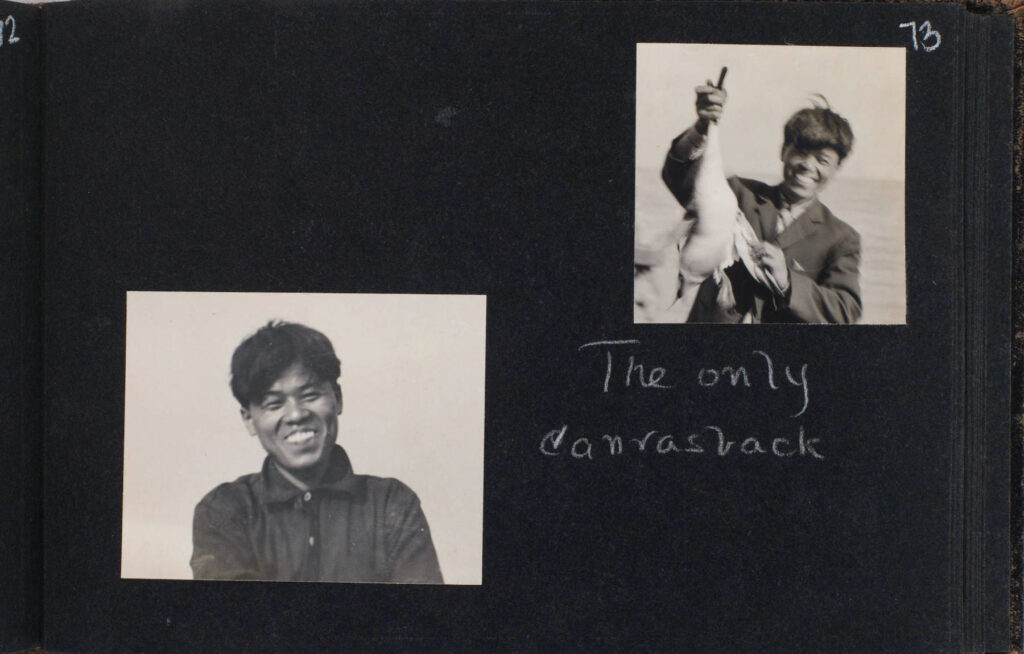

Nakata was born in the small fishing village of Okikamuro, Japan, on April 20, 1889. He migrated to Hawaii at sixteen years old in 1905. He didn’t speak a word of English when he joined the Snark voyage two years later but won the crew over with his radiant smile and cheery countenance. Charmian London, Jack’s wife, wrote of Nakata in her published book The Log of the Snark: “There is something fascinating about him, his ready smile, his cheerfulness, his temperamental happiness — like some wild thing of docile instincts. His frank expectance of kindness, as expressed in his winning bearing, brings him goodwill all around.”

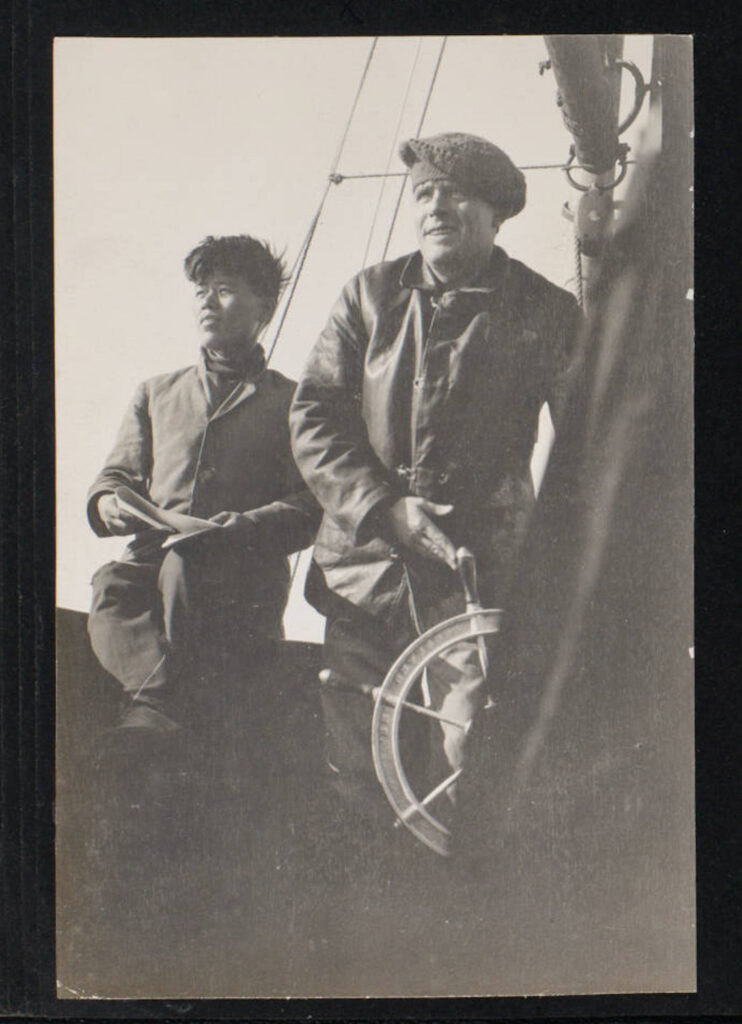

The Snark sailed the South Seas for two years before London had to abandon the trip due to ill health. He returned to California and brought Nakata with him, and over the next six years Nakata lived with the Londons at Beauty Ranch (now Jack London State Historic Park); sailed around the Horn on the tall ship Dirigo; and was first mate on the Roamer, the last boat London owned and which he sailed for months at a time on the San Francisco Bay. To London, Nakata was more than a valet or first mate. “Nakata has so endeared himself to Mrs. London and me that he has become to us more a younger brother or son,” London said.

This is somewhat surprising, given London’s often blatant racism and anti-Asian statements he made after covering the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. His daughter Joan London wrote in Jack London and His Times that her father had denigrated Japanese officers during a socialist meeting in Oakland after returning from Asia.

“I am first of all a white man, and only then a socialist,” he bellowed after an attendee reminded him that Japan also had workers caught up in a class system opposed by socialists.

In his essay “The Salt of the Earth,” London spoke of “the strong breeds, clearing away and hewing down the weak and less fit.” According to one scholar, after the Russo-Japanese War, he counted the Japanese among the strong.

Yet, according to Nakata, London treated his Japanese staff well, and his guests regarded them as friends, not servants.

Nakata worked hard, but he also rode horses for pleasure, swam and fished in the pond, and participated in parlor games with guests. On the Roamer, he and London played a rough game of keep away. They also bet who could catch the most rockfish at their favorite Angel Island fishing spot, though London didn’t stand a chance against the boy from Okikamuro where fishermen specialized in hand-line fishing. In one of the few entries written in English, Nakata said, “We fished in afternoon. Mr. London and I made a bet, and I won 40¢ and I also won 10¢ from Mrs. London catching bigger fish than she did. Oh, we had such a good time.”

To my knowledge, no previous biographers have translated or used the diaries. After I made the discovery, several London scholars told me that they did not know the diaries existed, possibly because they are not in the Bancroft’s Collection of Jack London Papers. Instead, the diaries are in the Partington Family Collection. Blanche Partington was a lifelong friend of London’s, and after his death in 1916, she maintained a close relationship with Nakata. His diaries found their way to the Partington family, and eventually the Bancroft Library.

I have not yet seen all the translations but those I have seen reveal Nakata as a meticulous person. Here’s one 1914 entry adapted and translated by Professors Muto and Mori:

Sept. 24 Fine 75° Got up at 5 o’clock Went to bed at 11 o’clock I got up early and roused Mr. London. We started soon. No wind and we moved forward till about 8 o’clock, Mr. London did daily work. At 3 o’clock in low tide water we sailed on. A strong southwest wind was blowing. That’s a headwind [and] the sail was very hard, but the condition of wind was favorable, so the Londons landed about 7 o’clock. Sano [the Japanese cook] cooked nice dinner and Mr. and Mrs. London went to bed at 490 [the address of their house in Oakland].

Decades after London died, Nakata commented on his boss’s smile. “No matter how heavily he was sleeping, I would just touch him, and he would wake up with that wonderful smile on his face as he looked at me,” Nakata said during an interview.

But it’s Nakata’s radiant smile that shows up in photos, whether taken aboard the Snark, on a four-horse carriage ride to Oregon, or at the wheel of the Roamer. It seems to me that London’s “wonderful smile” upon waking was in response to Nakata’s own exuberant life force.

Journalist and author Aleta George writes about the nature, history, and culture of California. She is the author of the award-winning biography “Ina Coolbrith: The Bittersweet Song of California’s First Poet Laureate.”