Fifty years ago the Oakland Museum of California acquired the largest collection of Dorothea Lange’s photography in the world. It was donated by her husband, Paul Taylor, after Lange’s death in 1965 and contains more than 25,000 negatives and 6,000 prints. Curator of Photography and Visual Culture at the museum, Drew Johnson (who graduated from UC Berkeley in 1983 with a degree in history, specializing in the history of photography), had the task of organizing the photographic trove into a single exhibition, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, which opens on May 13 and runs through August 13.

“The first thing we had to do was decide on a meaningful way to approach her work and to not just gloss over everything she did,” Johnson said. “She was an activist as well as a photographer, and her greatest goal was living a visual life, so seeing the world and helping other people see it as well.”

Lange started as a portrait photographer, and that experience carried over into her documentary work, Johnson thinks. For instance, she was used to shooting people from below, so as to show them in their best light. She would talk with them and put them at ease.

“She wasn’t surreptitiously capturing people,” Johnson said. “She would spend time making them feel comfortable, asking them about how many kids they had, for instance. Her pictures were almost a collaboration with the subjects.”

The show begins with a brief introduction to Lange’s early life. The rest displays about 130 of her photos, divided into three sections: “The Depression Woke Me Up,” “World War II at Home,” and “The New California.”

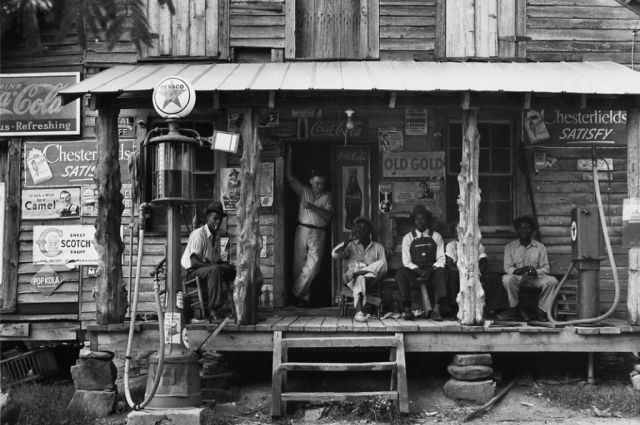

The first section contains Lange’s best-known photo series of Dust Bowl migrants in California, including Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, which is one of the most iconic photos of all time. (John Ford, when he directed John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, used Lange’s imagery.)

The second section features Lange’s photos taken during WW II, when 120,000 ethnic Japanese (two-thirds of whom were born in the United States) were interned in camps. These powerful and moving photos are not as well known because the U.S. War Department which hired her released very few of them. Johnson says her brief was to show that the Japanese were treated humanely, but the photographs are heartbreaking—a dignified grandfather waiting for an evacuation bus, belongings piled on the sidewalk, a the grim structures at the Manzanar camp—and it’s easy to see why the War Department didn’t use them.

The show includes other rarely seen photos of hers, such as her series on ship workers in Richmond. “I love this photo,” Johnson says, pointing to the 1942 Woman Standing in front of Richmond Cafe. “From her expression you can tell she has a steady paycheck.”

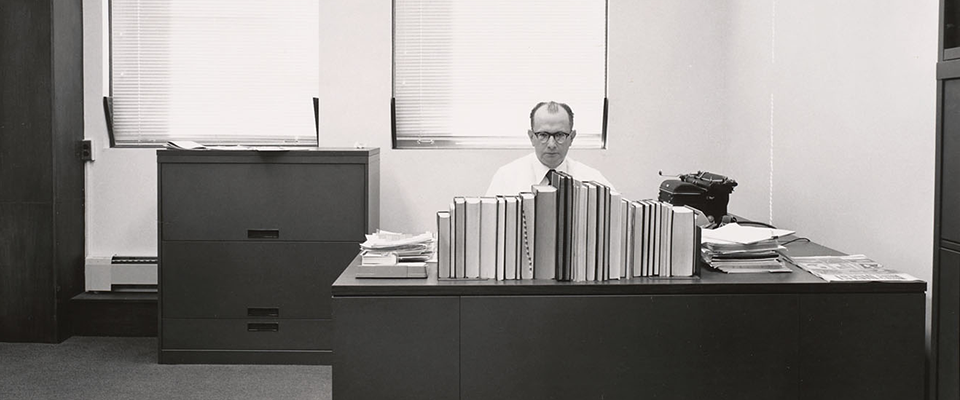

Johnson also shows a 1957 series Lange did on an Alameda County public defender, including a police badge, a jury, and a jail cell. Visitors may be surprised by how local the photos are, Johnson said. That photo of internees’ belongings on the sidewalk was taken right in front of where the museum sits today, for example. And the public defender Lange photographed worked in the courthouse across the street.

A gallery in Oakland showed Lange’s first documentary photos—of a May Day general strike and rally in San Francisco. Taylor, a UC Berkeley economics professor who wanted to take pictures to augment his writings on farmworkers, went to the show and was captivated by them—this style of pictures was new at the time, Johnson says. Taylor asked to meet Lange, and it was an “instant romance” said Johnson, leading them both to divorce their spouses (Lange’s was Maynard Dixon, the painter who focused on the American West).

Roy Stryker, the manager of the Farm Security Administration, saw Lange’s photos, and was captivated by them. Johnson said while working on this show he learned how instrumental Lange had been—she changed Stryker’s whole direction to focus on the plight of the rural poor. Other famous photographers, including Gordon Parks and Walker Evans, worked in the program, but as the only West Coasters, Lange and Taylor collaborated on documenting the migrants looking for work.

Throughout the exhibition are photos by contemporary photographers who were influenced by Lange: Ken Light’s 21st-century farmworkers hang in the section on the Depression; Janet Delaney’s gentrification of San Francisco’s South of Market neighborhood are in the post-war section; and Jason Jaacks’s U.S.–Mexico border works are near pictures of the Japanese internment. All of these photographers have written about how Lange influenced them. They aren’t alone, Johnson says.

“I’ve been doing this for 25 years,” he said. “I’ve lost track of the number of times photographers have told me Dorothea Lange was the inspiration for their work.”