In the July 2 issue of The New Yorker, Andrew Marantz explores how “social-media trolls,” led by alt-right provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, played leading roles in the university’s great free-speech clash of 2017. Which, despite the public spectacle, sparked needed conversations about the question of free speech: what it is and what it should be.

CALIFORNIA was all over the drama and intellectual debates roiling the Cal community as they went down. Here’s a recap of our coverage.

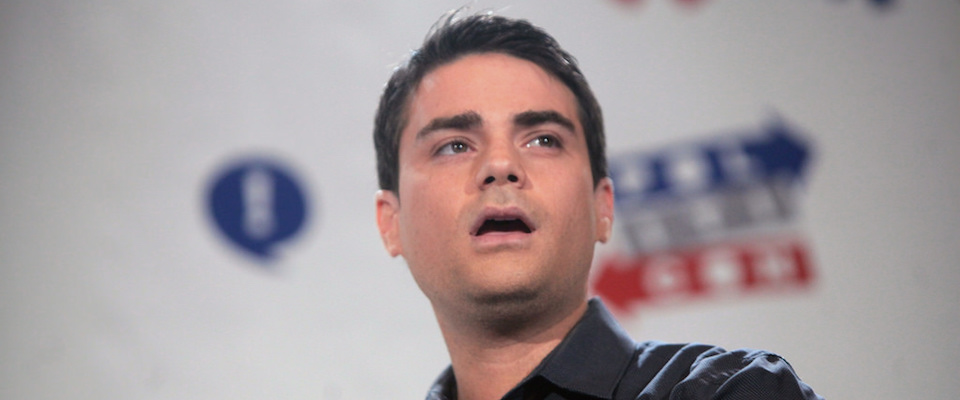

In the shadow of Shapiro

As “Free Speech Week” approached, CALIFORNIA’s Krissy Eliot braved tight security and aggressive signage to cover the speech by conservative, Ben Shapiro, who spoke last September in Zellerbach Hall.

Carol Christ, less than three months into her chancellorship, had proclaimed a year of free speech, and the Shapiro event showcased the lengths the university went to adhere to that. After the mayhem of the previous February’s Yiannopoulos no-show, Cal was taking no chances: Eliot recalled walking blocks uphill for her ticket, getting frisked outside the entrance, and described how “every barrier was guarded by a swarm of cops in riot gear.” And the whole thing only cost $600,000.

After the speech—where Shapiro rehashed his major talking points—a small protest erupted. A Ph.D. student “said he wasn’t protesting, but merely showed up to see how polarized Berkeley had become.”

“Yeah, I think a lot of people just came to watch,” a friend of his added.

Grist for Christ

In our Winter 2017 issue, Chancellor Christ offered her take on the eventful year. The “Free Speech Week” hullabaloo and the Shapiro event were a wake-up call to Christ about just how thorny the issue of free speech on a university campus can be.

“I came to realize that free speech must be more than a set of principles, that it must be a process of engagement,” Christ wrote. “There are unsettled areas of the law: what expense is reasonable for an institution to incur in the protection of speech, what regulation of time, place and manner is appropriate, what constitutes a sufficient security threat to justify cancelation of an event.”

To boycott or not to boycott?

Dozens of Berkeley faculty members signed onto a proposed boycott of classes and activities from Sept. 24–27. Though at the time, “Free Speech Week” hadn’t officially been sanctioned (pending a laundry list of unfulfilled logistical obligations by the inviting student group), and its key speakers hadn’t confirmed (or even learned about the event). The letter said the boycott was necessary for “keeping our students and our campus safe” during what was promised to be several days of inflammatory talks.

“We’re touching on feminist scholarship, technology, race and religion,” said Charis Thompson, Chancellor’s Professor in the Gender and Women’s Studies department, about a course she teaches. “So almost every topic that Milo has announced that he’s going to be covering as things to target is part of the scholarly inquiry of my class. It feels targeted as a class.”

Behind the bedlam

In February 2017, Yiannopoulos was slated to give a talk on campus. Protests turned violent after masked agitators saw an opportunity to destroy campus property, and the talk was cancelled. After the window-smashing, blaze-inducing, headline-grabbing bedlam following Yiannopoulos’ no-show, frequent CALIFORNIA contributor Glen Martin asked whether this was truly a free-speech issue or just some kind of sick joke.

Martin looked at the university’s begrudged stance that it couldn’t stop the publicization of undocumented students’ names (which it was rumored Yiannopoulos planned to do). He also wondered whether the “Black Bloc” disruptors were indeed hired by Yiannopoulos to jeopardize the university’s funding, and noted that shutting down a protest or protected speech requires a “clear and present danger.”

Jesse Choper, professor emeritus at Berkeley Law and constitutional law expert, said administrators did their best out there: “They let Yiannopoulos speak, because they had no real legal justification for stopping the event. They allowed the demonstrators to demonstrate, and dealt with the black bloc when they started destroying property. I don’t come down on the side of the university all the time, but I think they did the right thing in this case. They balanced values and costs.”

If one thing was clear, though, it was that the attention-seeker at the heart of the speech/protest/riot got more attention than he could ever hope for.

Digging in deeper

Last year’s drama was more than just police barricades, protests, and expensive photo ops, however. Rather than quarreling over whether the university properly adhered to established interpretations of free speech, the deeper intellectual debate considered whether our current notions of free speech are ethical and healthy for the university, and democracy as a whole.

Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky said censoring the speech of one person or group—no matter how offensive or false—is a slippery slope that could stifle the free flow of ideas, especially at an institution of learning. “If today you can stop the speech that I find offensive, tomorrow people can silence me because they find me offensive,” he said.

African American studies professor Michael Cohen contended that Free Speech Week “was deliberately designed to offend as many people as possible and to take up as much space on campus so as to prevent the workings of the campus from being carried out…. To halt and thwart the educational mission of the university, not advance it.”

Cohen asked, “Why would the university—whose singular message and mission is educational and research oriented—invite people with such utterly backwards, amoral and contemptuous ideas to use their platform to recruit and spread hatred sexism and violence?”

The question exasperates campus spokesperson Dan Mogulof, who stressed in an email that “the university did not invite a single one of the speakers in question. All were invited by a student organization with independent legal standing as a separate entity from the campus. We had no more ability to interfere with their invitation rights then we do with the Warriors’ decision to pay Kevin Durant 40 million dollars a year.”