The link between Russian hackers and last week’s WikiLeaks release of 20,000 Democratic National Committee’s internal emails may never be proven conclusively. However, a federal investigation has reported that the leak was probably conducted by Russian hackers and orchestrated by the Federal Security Service (FSB) and the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU)—two of Russia’s major intelligence agencies.

Given that the leaks landed right ahead of the Democratic National Convention—which you could consider horribly or perfectly timed, depending on your party affiliations—the logical question is: “What exactly does Russia’s President Vladimir Putin have against Hillary Clinton?

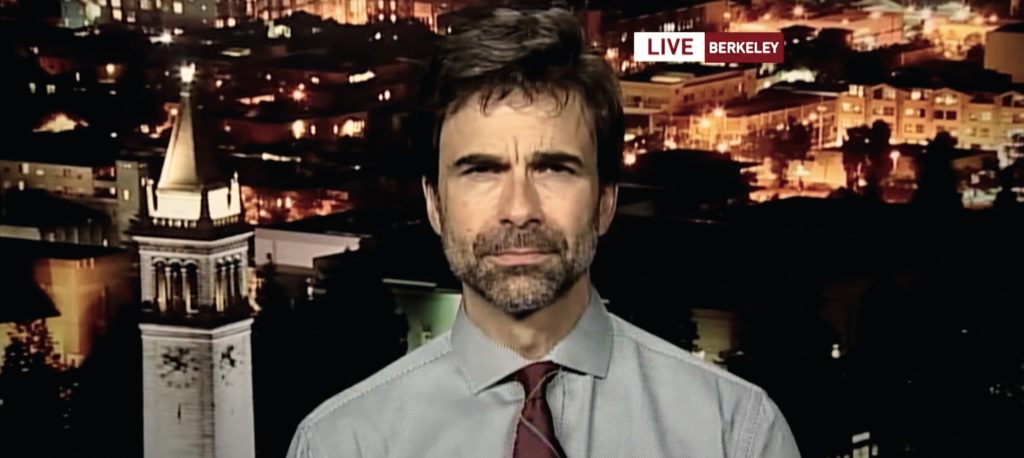

“The Russians really do not like Clinton,” said Edward Walker, the executive director of the Berkeley Program in Eurasian and East European Studies. “They don’t like her because they think she’s a hawk, which is not a completely unreasonable conclusion, and they think she’s a hawk in particular in respect to Russia, which again, is not an unreasonable conclusion.”

Steven Fish, a political science professor at UC Berkeley, explained that Russian interference in an American election is highly unusual—especially an organized cyber attack on this scale. But, he noted, there has never before been a Donald Trump in American politics, and his presence in the election has created a once-in-a-lifetime opening for Putin.

“Putin would love to see Trump win,” Fish said. “There’s never been a candidate in an American election who has been this malleable, who’s been this open to Putin’s blandishments, and this capable of driving a wedge between countries within the Western alliance.”

Fish noted that Trump has a long relationship with Russia’s business community dating back to the 1980s when he first visited Moscow searching for investment opportunities. Over the years, as U.S. banks shut their doors on the debt-burdened Trump, he relied more and more on Russian money to fund his projects.

Because Trump has refused to release his tax returns, it’s difficult to know the extent of his connections to Russian capital. But there are hints that it is extensive: Earlier this year, a New York Times investigation revealed that Trump’s Trump SoHo hotel in Manhattan likely was secretly financed by Russia and Kazakhstan.

Trump has also surrounded himself with political advisers who have extensive ties to Russian individuals and entities. Trump’s de facto campaign manager, Paul Manafort, spent recent years as an advisor for Viktor Yanukovych, the former Prime Minister of Ukraine who was deposed in 2014—in part for his strongly pro-Russian sentiments. Trump’s foreign policy advisor, Carter Page, has financial ties to Gazprom, Russia’s state-controlled energy company.

As Fish pointed out, Putin knows that he can take advantage of these personal and financial links to exert influence over a Trump administration.

“This is the dream: Without firing a shot, Putin would feel that he’s actually able to undermine the West,” Fish said.

There are already tangible signs of how Trump would change U.S. policy regarding Russia. During an interview on July 21, Trump hinted that as president, he wouldn’t provide military support to NATO members who aren’t meeting their financial obligations. Only five of NATO’s 28 member countries—including the United States—follow the NATO recommendation of dedicating 2 percent of their GDP to defense spending.

“Trump’s language about NATO and his suggestion that the United States would not consider Article Five of the NATO Treaty to be binding is manna for Russians—music to their ears,” Walker said.

“There’s a huge schadenfreude element to all of this. Russians feel like we’ve been screwing them for a really long period of time, and many of them would love to see us screwed.”

By weakening NATO, Trump would alienate the U.S. from its Western allies. According to Walker, this would be relished by many Russians, who have a deeply ingrained belief that the United States and Western Europe have conspired for decades to keep Russia isolated on the global stage.

“There’s a huge schadenfreude element to all of this,” Walker said. “Russians feel like we’ve been screwing them for a really long period of time, and many of them would love to see us screwed.”

Both Fisher and Walker observed that Americans are, by and large, oblivious to the animus driving Russia’s competitiveness with the United States.

“Russians are still obsessed with American power—they’re jealous of it, they’re awed by it, and they resent it,” Fish said. “Most Americans don’t think much about Russia except when Russia is causing problems in international relations [but] Russians think about the United States all the time.”

In this sense, Trump represents a unique opportunity for Russians: electing him would, at the very least, humiliate the United States, and especially the Republican Party.

“You’ve got a candidate for president from the Republican Party who is cozying up to a Russian dictator,” Fish said. “It’s a beyond-radical shift for the Republican Party—they’ve never seen anything like this since World War II.

Trump has done little to quell fears in his own party that he’s too intimate with Putin and his ilk. In fact, he’s suggested that he would welcome more Russian interference in the election. During a press conference yesterday in Florida, Trump called on Russia to hack Clinton’s email to recover lost messages: “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing,” Trump said.