The inaugural edition of The Berkeley Barb hit streets on Friday, August 13, 1965—incendiary times. It was the first days of the Watts riots, and the conflict in Vietnam was beginning to play out in living rooms on the nightly news. That week TV viewers watched as American GIs casually torched Vietnamese villages with their flamethrowers and Zippo lighters. Meanwhile, all across the United States, disillusioned young men were beginning to take those Zippos to their draft notices. To a kid in Berkeley in that era, it must have seemed as if the whole world was going up in smoke.

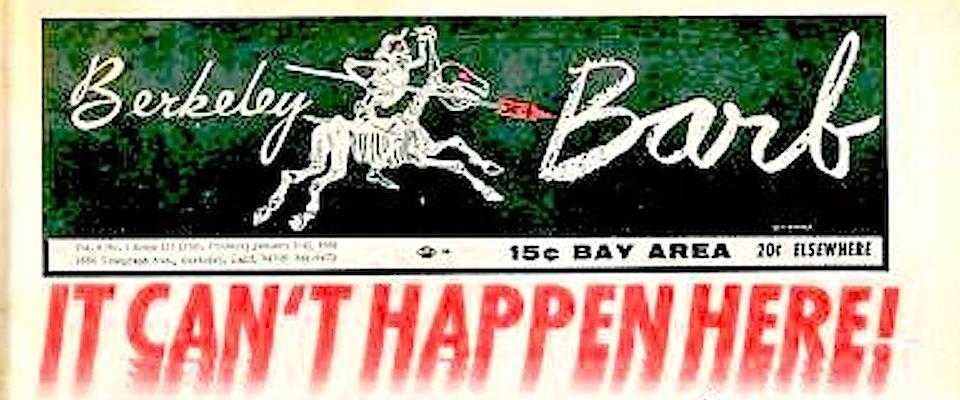

It was against that backdrop that the heavily bearded Max Scherr, an aging lawyer/bohemian saloonkeeper with roots in the Old Left, appeared clutching copies of his new underground paper, The Berkeley Barb—a weekly tabloid that would feature news of the revolution… and sex… and drugs…and the next Jefferson Airplane show. The masthead was inspired by Jorge Posada’s La Calavera de Don Quixote, the skeletal rider on his skeletal steed, lance leveled for battle. As the tip of the lance, Scherr, who held a bachelor’s degree in sociology from UC Berkeley, put the campus Campanile.

The first run was only 1,200 copies and, in the beginning the publisher doubled as newsboy, hawking his product on city street corners. Price per copy: Ten cents. “Read the Berkeley Barb,” Scherr called out. “It’s a pleasure not a duty.”

Folks seemed to agree. By 1969, circulation had grown to 93,000 and the Barb had become the leading voice of Berkeley radicals and an institution of the New Left. And, as it so often goes with the Left, it also engendered internal dissent, labor strikes and splinter factions. In time, Max would be denounced by his own erstwhile staff as petit bourgeois and a capitalist pig.

But that all came later. In the early days, Scherr’s Barb was where it was at.

Writer and satirist Paul Krassner, sometimes called the dean of underground journalism, covered the Patty Hearst trial for the Barb—a saga he recalls in his latest book, Patty Hearst and the Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials. He compares the Barb to “the unregulated Internet before there was such a thing. I mean, anything went in those pages. It was so free.

“There was a sense of community around it,” Krassner adds, “so that even when people left Berkeley, they kept subscribing because that was their social media. That was their connection to their people.”

Krassner also published his own paper, The Realist, favored reading material of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, who flipped through it on their famous psychedelic bus as they tootled around the country, high on acid and morning glory seeds.

There were other underground papers in the Bay Area at the time as well, but they tended to be more narrowly targeted; The Oracle to “the heads,” the Express Times to the political activists. The Barb was unique, says former contributor and Free Speech Movement alum Kate Coleman, in being “the only one that brought the whole counterculture together—drugs, rock ‘n’ roll, free speech, free love, politics—all of it.”

Scherr, who died of cancer in 1981, not long after the Barb itself gave up the ghost, will be remembered next week at a trio of events to mark the 50th anniversary of his newspaper’s debut. The occasion will serve as a reunion of the loose-knit tribe of contributors and employees who produced it across a 15-year span.

Here’s what’s on tap: On the night of Wednesday Aug.12 there’s a party for former staff and contributors, followed by a free concert by hippie troubadour Country Joe McDonald and friends.

On Thursday Aug. 13, it’s a series of panels and speakers, including a keynote by Eugene Schoenfeld, a physician who back in the day doled out health and sex advice in the Barb under the byline Dr. Hip(pocrates)—advice that ran alongside racy pictorials, explicit personals, and a bevy of advertisements for massage parlors, the Barb’s bread and butter.

On Friday Aug. 14, it’s a film festival featuring documentary fare, including Berkeley in the Sixties (natch), Let a Thousand Parks Bloom (about People’s Park), and Hookers, a Scherr-produced film about feminist-prostitute Margo St. James, who campaigned for the legalization of her profession.

The main mover behind the event is Barb historian and archivist Diana Stephens, who wrote her masters thesis at California State University-East Bay on gender politics at the paper. That was a rich vein to mine, for while the Barb was editorially feminist, it also traded in quasi-pornographic content and the aforementioned sex ads.

“There were massage ads up the ying-yang!” recalls Coleman, engaging in some pre-reunion reminiscences for California. “In those days, Berkeley had more massage parlors than hands!”

Not surprisingly, many of the female staff took issue with being roped into the skin trade. Kathy Streem, now a retired public defender, remembers when the masseuses would drop by to pay for the ad placements. “I tried to organize them and encourage them to strike for better pay and working conditions.” She even took to the streets. “I had a sign that said, ‘Off the Pimps!’ ”—a riff on the Black Panther rallying cry, “Off the Pigs!”

For his part, Scherr tolerated feminist editorials but didn’t suffer them gladly. A feminist tract written by female staffer Judy Gumbo appeared, much to the writer’s chagrin, under the Scherr-supplied headline, “Why the Women Are Revolting.”

Mostly, he was keen on getting more nudity into the Barb’s page. “’Tits above the fold!’ was Max’s motto,” recalls John Jekabson, former managing editor of the Barb. With a shrug Jekabson adds, “Sex sells. It sold then and it sells now. Max understood that.”

The sex certainly sold, but it also led to an obscenity bust, after the Barb ran photos showing members of the rock band MC5 engaged in group sex with a groupie. The raid only served to reinforce Scherr’s stature in the Berkeley counterculture, which, given the legacy of the Free Speech Movement, was united in its opposition to all forms of censorship.

From the beginning, the Barb ran on a shoestring and the famously tight-fisted Scherr nickeled-and-dimed writers and staff. Streem remembers doing the layout as Scherr hovered over her shoulder, urging her to widen the margins. “Max paid by the column-inch,” she explains, laughing. “If I widened the margins, I saved him money.”

As the paper grew, the sales force was plumped out with underpaid contributors and starving hippies. One such specimen, a cat named Crowbar, is quoted on the reunion website, recalling how he and friends sold the Barb on San Francisco’s Haight Street. “That’s how we lived: made enough money every day to buy a loaf of bread, peanut butter, jelly, a hit of acid, and a outrageous priced ticket ($2.50) to the Fillmore or the Avalon to hear some cool music.” Crowbar says the Barb saved his life.

Not everyone found their arrangement with Max so copacetic. Discontent boiled over in 1969 after a mysterious, short-lived paper called the Berkeley Fascist appeared, in which it was calculated that the Barb netted $5,000 an issue. Adjust for inflation, multiply by 52 and that translates to roughly $1.7 million a year in 2015 dollars. Apparently Max Scherr, the old Marxist, was getting rich off the backs of the workers.

Years later, Gar Smith, FSM veteran and a reporter who covered the “peace beat” for the Barb, would reveal, in an article for New West, that Scherr had for years been socking money away in offshore bank accounts. What was he saving for? John Jekabson says it was part of a long-term plan to build an alt-press empire: “I think he wanted to become the William Randolph Hearst of the counterculture.”

Whatever the case, staff members at the time were understandably outraged by the revelations in the Fascist and soon went on strike. Then, after trying and failing to buy the paper, the majority defected to start their own competing weekly called The Berkeley Tribe, led by Yippie co-founder Stew Albert. More strident than the Barb, the Tribe’s rhetoric was often as subtle as a rock through a windowpane. At times it was simply hateful. After a rookie Berkeley cop named Ronald Tsukamoto was gunned down on August 20, 1970, allegedly by members of the Black Panthers, the Tribe ran a full-page photo of the fatally wounded young officer under the headline “Blood of a Pig.”

Although the Barb didn’t shrink from the radical rhetoric of referring to police as pigs, it would never have stooped to gloating over a slain officer’s body, insists Kate Coleman. She acknowledges, however, that she herself was swept up in the militancy of the times. “I was carried away, until I wasn’t,” she says, remembering the moment when her old friends in the Weathermen started setting off bombs as the Weather Underground. “And it dawned on me. Oh, now we’re fucking terrorists!”

The Tribe would fold in 1972 but the Barb soldiered on until 1980, although by that time, Scherr was no longer owner, having sold off his interests. Just as well. By then Berkeley was no longer berserk but merely quirky, and politically the Right was ascendant. Just weeks before the Barb’s old nemesis, Ronald Reagan, accepted the Republican nomination for President, the paper’s last issue appeared in print. “The Barb Bows Out” read the headline. A front-page illustration showed the skeletal Quixote of the masthead slumped in the saddle, the Campanile-tipped lance protruding from his back.

In his book, Uncovering the Sixties, journalist Abe Peck quotes Max Scherr from his death bed, reflecting somewhat bitterly on the counterculture’s accomplishments and failings. “We were a lot of well-meaning fools,” Scherr lamented. “All of us were tainted by the environment we were brought up in. We had no revolutionary base, no real class consciousness. Along with the good, we developed a large rip-off philosophy.” At the same time, he said, “We broke down a lot of barriers to honest thought and opened up a whole visionary realm to the future, which has to be worked on.”

More information about the events planned for the Berkeley Barb reunion is listed here.