When Chris Chambers, 55, moved into Oakland’s Lakehurst Hotel, he went from sleeping by the Walgreens on Telegraph Avenue to sleeping in a tiny hotel room in a place where he wouldn’t allow himself to get close with any of his neighbors. But he was used to being alone.

“I would get up, and then go back to bed,” he recalls. The cycle would repeat: wake up, get up, maybe go to a group therapy session, maybe not, go back to bed, and eventually, get up again. He’s disabled, and his room doesn’t come with a bathroom, so he has to hobble to the bathroom out in the hallway. “I got a bad leg for life. You can’t do no surgery or nothing,” he says. “I’m messed up. I have no family. No one is going to do anything for me. Do what you have to do to take care of yourself.”

His story is not unique. Most of the roughly 110 residents who live in the Lakehurst—a residential hotel nestled between a glistening Lake Merritt and pricey downtown—battle mental illness and live on a meager Social Security income. For these residents, the isolation forged by both combines with the isolation of living in a hotel room. Breakfast and dinner are served in the dining room, where each table has one chair, as though meals are meant to be enjoyed alone. The lobby offers two chairs, where residents sit by themselves, staring out the window.

It wasn’t always like this. For more than a year up until last summer, friendly visitors came to the hotel to lead residents in a song circle, perform yoga exercises together, and make artwork. Officially, it was called the Culture of Inclusion project, but residents nicknamed it “lunch bunch.” And although it has ended, the lunch bunch offers an instructive model of what happens when the mentally ill begin to feel less alone.

The project was created by T. Anne Richards, a former UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco researcher, and Margot Dashiell, a mental health advocate.

“Serious mental illness can be very isolating. Depression, bipolar disorder, and particularly schizophrenia are conditions that can cause withdrawal. They’re illnesses where people lose touch with others, where they lose touch with reality,” Dashiell says. “It only gets worse if they’re isolated, and if you’re in an environment that doesn’t break down isolation, it only worsens the problem.”

In California, SROs have been a catch-all for some of the neediest people for decades, as UC Berkeley emeritus professor of geography and architecture and geography Paul Groth made clear in his book Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States, published by UC Press. “By 1960, welfare departments were sending more unemployed downtown people—especially the elderly—to hotels for temporary housing that tended to become permanent,” he writes. “In the mid-1960s, the well-intentioned (and budget-cutting) decision…to mainstream mental hospital populations had been coupled with promises of halfway houses and group homes…However, the halfway houses were never established. Patients were essentially dumped into downtown hotels where neither hotel staff nor residents were prepared for the care required by these new neighbors.”

Research in recent years has pointed to the problem of social isolation within the SROs, including a study sampling San Francisco’s 18,500 SRO residents by Goldman School of Public Policy student Aimée Fribourg in 2009. “Some residents may have no friends, no family, and/or no telephone,” she noted. “Many have scarce or limited support systems, especially when there are no on-site case managers. Interviewees noted that some SRO residents may behave as if they were homeless by spending all day outside, often in unsafe environments, and coming home only to sleep.” Her conclusion, based on data and interviews: Seniors and adults with disabilities who live in SROs are generally more socially isolated than their non-SRO-dwelling counterparts, and often need a broad range of comprehensive support services.

“The innovation grant program is for trying new things, testing things out, so that’s what we were doing,” says Richards. “We didn’t know going in if yoga would work, if music would work. The whole idea was to develop a sense of community, a sense of belonging.”

Richards had conducted research on medical ethnography for the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program, and taught seminars at Berkeley on qualitative research methods. Over the years, she had become familiar with the culture of single room occupancy hotels (known as SROs) while studying the AIDS epidemic, and later, working with low-income seniors in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood. Dashiell, vice president of the National Alliance for Mental Health’s local branch, has been leading an African American support group for families dealing with mental health issues for more than a decade. With two Berkeley degrees—a bachelor’s in sociology and a master’s from what used to be the School of Criminology—she says the she brought to the Inclusion Project an approach consistent with the focus of her education: “to develop programmatic designs to work in assisting the reintegration of people back into community.”

For Lakehurst owner Tomoko Nakama, running a hotel occupied almost entirely by those who suffered from mental illness already was an experiment. “It was an accident,” she says, explaining that when she acquired the building in 1996, it already housed mentally ill residents, who provided a stable funding source by paying rent with their Social Security benefits. “I didn’t know what to do with the mentally challenged people. I didn’t know how to make a menu. I had to staff the front desk. It was like hell. But I learned. I made contact with mental health services, with case managers. They need this building for their clients, so they were willing to help me. So I got smarter.”

So she welcomed the Culture of Inclusion Project, for a small fee, into the Lakehurst two to three days per week for a year. I wanted to know how it worked and how beneficial it would be for my tenants,” Nakama says. “And for those who participated, they flourished.”

Richards and Dashiell set up tables, and introduced themselves to the residents. They asked them what kind of programs they would want in their homes.

One of those residents was James Storey, who arrived after rent increases forced him to leave his home in the Diamond District and left him homeless for about a month. The first week he moved into the Lakehurst, another resident had tried jumping off the roof. “No one really talked about it as a community,” he remembers. “The building reminded me of a haunted hotel. It’s spooky and depressing. It’s in shambles. I found structure outside, but I’d come back to the hotel, and think, ‘What am I doing here?’”

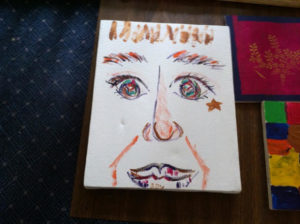

Then he discovered the Culture of Inclusion Project. “I just walked downstairs one day, and I went to the dining hall, and there was a group of people there doing artwork,” Storey said. “I was at a place in my life where I wasn’t in very good head space. I thought, ‘This is really cool, this is where I can come and get some headspace together, meet people, and talk.’ ”

Each week, artist Ximena Soza would bring in different supplies, and she’d ask the residents what they wanted to make. They created pillowcases and ceramics, took photographs, decorated cupcakes. “We have a lobby for people, but there’s no games. Nothing goes on in the lobby. Some people go out and collect spare change, they smoke cigarettes, they might go out and eat a bag of chips,” says Arianne Hastings, another resident drawn to the artwork. “But with the project we were doing something positive.”

Musician Ken Thames showed up to lead a song circle, bringing in his piano and guitar. Music filled the lobby as the group sang uplifting songs together, eventually putting their songs into a book. “The song circle was really important for a lot of folks. It helped take the boredom out of life, especially the life that many of them have, which does not include a lot of social interaction, the kinds of activities that you and I, as functioning people, would be able to engage in,” Thames recalls.

Another resident discovered she could do yoga through the Culture of Inclusion Project. “I was in an awful state. It was really bad. It may have gotten worse were it not for that program, because it reminded me of things I like to do,” she says. “Yoga is key to my life. And then I found out they did artwork, and then there was a guy who sang and played a guitar. They served us lunch. They were so kind, and they were just talking to each other.”

Thames, the musician, had noticed how residents talk about how hungry they were on the weekends, when the hotel doesn’t serve meals. “I was sitting there, listening to that, and I just thought, ‘Wow, this is really sad. I’ve got to do something about this,’” he says. So on Fridays since, he has delivered food for residents to eat over the weekend. It’s a source many rely on, and a few wait outside for him. Many of the residents have also complained the hotel drinking water tastes like metal, and so he brings them bottles of water, too.

As the project progressed, field notes were kept, surveys collected, focus groups conducted. Residents told the researchers it had lifted their spirits, prompted them to make friends, and helped them feel less lonely. Many had talked or corresponded with family members more after joining the program. Each week, there were fewer involuntary psychiatric holds.

“There was one man who would go to the hospital as though it were a spa,” Dashiell recalls. “He goes to McDonald’s, he asks to be taken to John George (Psychiatric Hospital), and they said it happened at least once a week. He was with us for three months, and it only happened once.”

Residents, including some who originally would only sit in the corner and talk to themselves, “started to engage in real time,” Richards says. “But as we moved towards closing the project, there was one fellow who withdrew again. He went back to his internal world. It was just devastating.”

The project, which was funded by Mental Health Service Act money distributed through Alameda County Behavioral Health Care Services, was designed to be temporary, as such experiments are. The researchers, having found clear benefits from it, created detailed guidelines for anyone who wants to bring programs to the residences of those who are mentally ill. By mid-2016, those guidelines will be posted online so that “anyone interested in looking at the project and the impact can take it, revise it, and implement it in other settings.” Even so, she says of the Oakland experiment, “it was very, very difficult leaving there.”

After the project ended, the resident who initially fell in love with the program for the yoga began to see her neighbors drift away. “The place just went weird,” she says. “You could take photographs of them then and now, and you would see a difference. People like to collect data, but what sort of data shows the visible results I saw?” She adds that the same people she used to hold conversations with can now barely enunciate or speak. “They walk around like zombies now. Maybe that’s why I’m so angry. It’s really threatening. I don’t want to be a zombie. I don’t want to be like what I’m seeing.”

At the Lakehurst, life goes on. Chris Chambers, who arrived in August, never took part in the Culture of Inclusion project. As far as he knows, it never existed at all. He waits by the window. “Everybody here does their own thing, just minds their own business, you know what I mean?” he says. “Do what you have to do to take care of yourself, like everywhere else in Oakland. I would like to be in an apartment, but until that happens, I’m here.”

Newcomer Robert Johnson, a veteran, who keeps his saxophone and keyboard in his room and tries to strike up conversations with his fellow residents—even those with severe mental illness. “My friend calls them zombies. They’re not zombies. They’re living, breathing human beings you can interact with,” he says. “There was a guy who walks back and forth, but he makes conversation. I’m a people person.”

Nearby, longterm resident Billy Daniels takes over the spot by the window. He’s 62-years-old now, and he’s lived in the hotel for 11 years. He finds ways to fill his days. “I go to Chinatown, buy Chinese food, I go to Subway, I go to McDonalds, I go to Burger King, order a pizza, that’s it, that’s my life’s story,” he says. “I went down in life. That’s just the way it is. You’ve got to deal with it. You’ve got to live with it.”

But he remembers the Culture of Inclusion Project—it made a difference in his life, if only temporarily. He points out the window at a mailbox that he drew during the project. “The artist hung it on the wall. The project got me doing something. A lot of people were sad when it ended,” he says with a hollow chuckle. “When you run out of funds, that’s it.”