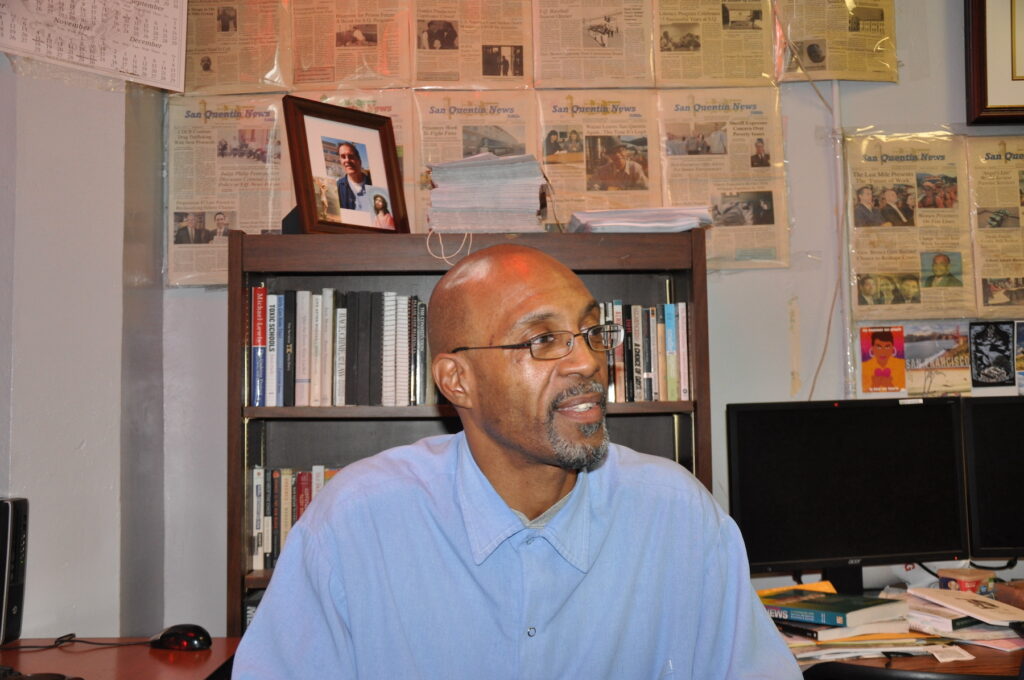

Kevin Sawyer is a man of many parts. He’s a certified commercial and residential electrician. A trained paralegal. A skilled guitarist and pianist. He holds a BA in mass communication and broadcasting, and he worked for 14 years in telecommunications. Perhaps most impressively, he’s a journalist with an acknowledged expertise in criminal law and several hundred publications to his credit. He was recently accepted to UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism.

He’s also an inmate at San Quentin State Prison serving an indeterminate life sentence for burglary and sexual assault. He has spent more than 26 years behind bars, and turns 60 this year.

Sawyer’s case is convoluted, involving three trials and varying testimonies and eyewitness accounts. Perhaps its most anomalous element is the simple fact that he’s still in prison. Many murderers, including some Sawyer has known personally, have served far shorter sentences. (The average time served for a second-degree murder conviction in California is 15 years.) Sawyer was up for parole last year but was denied, scotching any hope he had of matriculating at Cal’s J-School this fall. Unless he can win his release through a successful habeas corpus writ, Sawyer will have to wait five years until he is again eligible for a parole hearing.

So why is he still incarcerated? Sawyer has never been a violent or even fractious prisoner. He did receive a “Rules Violation Report” in 2021 for refusing to move from a tier one (bottom floor) cell to a tier four cell because he has osteoarthritis and couldn’t tote his belongings up three flights of stairs as prison officials required. Minor as that infraction may seem, the state Board of Parole Hearings cited it as evidence that he was “unsuitable” for release. In more than a quarter century behind bars, Sawyer says, he has received only one other RVR. In 2008, he was at California State Prison Solano when some prisoners declared a work stoppage. Sawyer says he did not participate in the strike, but he was included in a blanket citation that covered more than a thousand prisoners.

If the most recent RVD was given as a reason for Sawyer’s parole denial, there may also be deeper rationale at work, says Bill Drummond, longtime l faculty member in Cal’s Journalism department who also directs a journalism program at San Quentin in coordination with his graduate students.

“I’ve known Kevin for a long time, and a few qualities characterize him. He’s an intellectual – what people once called an ‘egghead.’ He’s extremely well read and well spoken, and of course, an excellent writer. He’s enigmatic. You look at him and you wonder, ‘What the hell are you doing in prison? ‘”

Sawyer, who is black, is also extremely proud, added Drummond, and a man who sees the world in terms of struggle, of bedrock racial injustices that must be resisted.

“He’s in the tradition of George Jackson and Eldridge Cleaver, and he’s also a remarkable jailhouse lawyer,” Drummond said, “and I think that’s really working against him [with the Board of Parole Hearings]. He’s been in a litigation war with the Department of Corrections for the past 20 years, he’s won a lot in court, and they don’t like it. He’s embarrassing them, and they’ve put a checkmark by his name.”

Indeed, Sawyer acknowledges he sometimes acts against his own interests – if not against his principles. An example: Asked by the Board of Parole Hearings why he did not have a score on the Test for Adult Basic Education, he said he had taken it once and didn’t intend to again.

“My record had a score of zero, indicating I hadn’t taken the test,” Sawyer said. “But I did take the test – in 1999, and I scored very high. But when the prison converted its paper files to electronic ones, they didn’t populate the required fields, and my score wasn’t recorded. So to prove my literacy, I submitted a package of my 200 articles published in the San Quentin News and 25 other publications, along with my paralegal diploma and transcripts and my electrician certification and transcripts. But I wasn’t going to retake the test. I wasn’t going to do something they’re required to do by law.”

Sawyer even wrote an essay about his stance on the matter for the Prison Journalism Project website. None of these responses likely endeared him to the people considering his parole, of course.

“It’s interesting,” said Sawyer. “If the Board finds anything negative in your record, they do their utmost to emphasize it. But they simply gloss over your accomplishments, over anything positive.”

Emails to the Board of Parole hearings received an automatically generated response, then no further contact. A phone call was not returned.

Paul Hoffman, a partner in the law firm Schonbrun DeSimone Seplow Harris & Hoffman and an adjunct clinical professor at the University of California, Irvine, School of Law, participated in a case involving Sawyer’s First Amendment rights.

“Kevin had personal documents, including materials related to Black activism,” Hoffman recalled, “and when he was transferred to San Quentin from another prison they were seized. He was using that material for his journalism, and it was clearly covered by the First Amendment. My students and I took on his case, and we were able to resolve that issue successfully.”

But echoing Drummond, Hoffman thought the win may have ultimately worked against Sawyer.

“As I said, it was a First Amendment issue, and it didn’t go to the heart of Kevin’s incarceration and sentence,” said Hoffman, “but I wouldn’t be surprised if it played a role in his parole denial.”

Like Drummond, Hoffman is impressed with Sawyer – as were his students.

“He’s a serious man,” Hoffman said. “I’ve talked to him about a number of his issues, not just his case, and he always has an interesting perspective. He thinks deeply and he researches meticulously – he did some very good writing on the effects of the Covid epidemic in prison, for example. He’s a genuine journalist, an accomplished journalist, and he has a lot of important things to say.”

For those reasons, Hoffman supports Sawyer’s parole.

“And I don’t say that lightly,” he said. “I’ve represented a lot of prisoners over the years, and he stands out. Of course, you always think – ‘What if I’m wrong?’ But parole, any parole, is a risk. And I think the risk with Kevin is about as low as you can get. “

Sawyer’s best chance for release from prison is through a writ of habeas corpus issued by a sympathetic judge. Hoffman is taking on a group of new students at his appellate litigation clinic at the end of August, and he has told Sawyer that they’ll try to assist him with such an effort.

For his part, Drummond feels habeas corpus is the only chance Sawyer reasonably has; the Board of parole hearings, he avers, “will never accommodate” Sawyer.

Which raises the larger question of “rehabilitation.” It is widely acknowledged among penology experts that incarceration solely for the purpose of punishment is ineffective, inhumane, and prohibitively expensive. And certainly, that’s Governor Gavin Newsom’s position. He has launched a new policy for the state penal system, emphasizing programs that prepare prisoners vocationally and socially for life beyond the walls. Newsom has made San Quentin a lead institution for this approach, renaming the forbidding hulk of stone and steel the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center.

That should redound to Sawyer’s benefit. So should his age. By prison standards he’s an elder, and his osteoarthritis makes him a minimal physical threat. These qualities also make him a significant financial burden for the California Department of Corrections.

“Kevin [is hitting his sixties],” says Drummond, “and it’s very expensive to incarcerate inmates as they get older and sicker. Older convicts cost the state about $100,00 a year, compared to the $50,000 or so it costs to imprison a young gunsel. You want to know why tuition is so high at the University of California? That’s part of it.”

And again, there are the bedrock inequities of Sawyer’s specific case, observed Drummond.

“He doesn’t have the cachet of, say, [Charles Manson follower] Leslie Van Houten, who committed truly heinous crimes,” Drummond observed, “but she’s out and he’s still in. I’ve worked with guys on the San Quentin News who committed homicides, and they’re out. And the irony, of course, is that Kevin killed no one. But there’s one other thing – the Board has a real problem with anyone who has anything ‘sexual’ on their rap sheet. The perils they see – well, they can’t handle it. And I think that’s a real obstacle for Kevin.”

Drummond doesn’t necessarily blame Newsom for a deliberate lack of follow-through on reforming the state penal system. It’s Chinatown, Jake – except it’s San Quentin, and every other prison in the system.

“It’s a structural problem,” he says. “I think Newsom genuinely wants to change it, but he can’t do it on his own. It’s too big, too entrenched. It’s resisting him, and that includes the Board of Parole Hearings.”

For his part, Sawyer seems to accept his setbacks with equanimity. He’s contemplating the proper approach to petition for a writ of habeas corpus; he continues to write; and he hopes, at some point, to attend the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. He’s used to waiting. After a recent interview, a reporter told him he’d try to reach him the following week.

Sawyer chuckled softly.

“I’ll be here,” he said.