In late May of 2022, UC Berkeley entered a time machine. A 1941 Ford was parked outside Wheeler Hall, shrubs grew where bike racks once stood, and vintage lamp posts decorated walkways. Campus once again became the backdrop to J. Robert Oppenheimer building up the theoretical physics department, only this time the scientist was portrayed by Cillian Murphy, star of director Chistopher Nolan’s blockbuster film Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer premiered July 21st, 2023, just over 78 years since the first nuclear detonation occurred at the so-called Trinity test site in New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto desert. In combination with Barbie, it became the fourth highest box office opening in history, sparking an explosion of interest in the father of the atomic bomb.

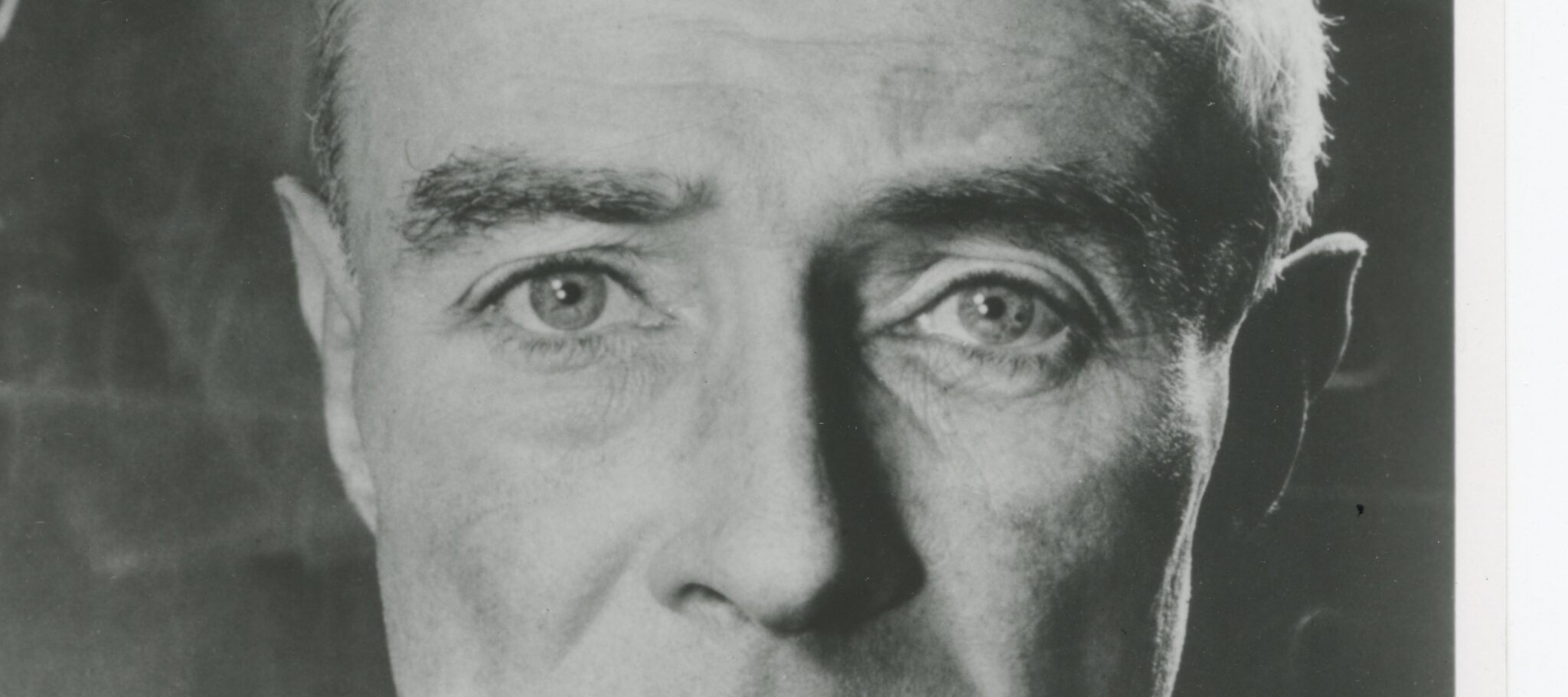

More than forty years earlier, Jon Else made the first documentary about the enigmatic scientist. Called The Day After Trinity: J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Atomic Bomb, it was nominated for an Academy Award and is available to stream as part of the Criterion Collection. For the film, Else, now a professor emeritus at UC Berkeley, interviewed key Manhattan Project scientists including Oppenheimer’s physicist brother, Frank, as well as New Mexico ranchers and residents about the impact of the world’s first nuclear test in Los Alamos. He also incorporated both archival footage of Oppenheimer, General Groves, and President Truman and recently declassified footage of Hiroshima.

Else traces his interest in Oppenheimer to the period in which he grew up: Born in 1944, before the first atomic bomb, Else came of age during the Cold War when “nuclear weapons were part of culture.” He spoke with California about the enduring urgency of nuclear stories and Oppenheimer as a modern mythological figure.

What sparked your interest in nuclear weapons?

When I was about eight years old, my dad took me out in the backyard [in Sacramento] before dawn, and we looked south, the sky lit up orange, and collapsed back down. It was a nuclear test. Nuclear tests were sometimes announced beforehand in the newspaper with the weather forecast. We did duck and cover and saw lots of civil defense movies in elementary school. Nuclear weapons were just part of the air we breathed.

How has our understanding of Oppenheimer changed since then?

I’m baffled at the sudden cultural urgency around Oppenheimer at a time when nuclear fear is a tiny shadow of what it once was. In 1960 the nuclear arsenal was phenomenally large … Many people thought nuclear war was an inevitability. We live in troubled times, but in the 50s and into the 60s, fallout was a huge concern. The entire globe was getting dusted on a weekly basis for radioactive fallout from Soviet and American testing.

Is it important to return to the story of Oppenheimer now?

Absolutely. Any story that brings nuclear weapons and the issues of controlling nuclear weapons back into the foreground is good for everyone. Any story that raises the question of the responsibility of scientists and leaders makes the world a better place. These stories have to be told, in new ways, every generation, by new storytellers.

Why do you think we are still so interested in Oppenheimer?

I think there’s some transference to our present existential problem with climate change. Nuclear war was and remains an existential problem, and the fact we have not blown ourselves up is quite a success story. We stepped up to deal with the prospect of nuclear war in a way we have not stepped up to deal with the equally serious, if not more serious, threat of climate change.

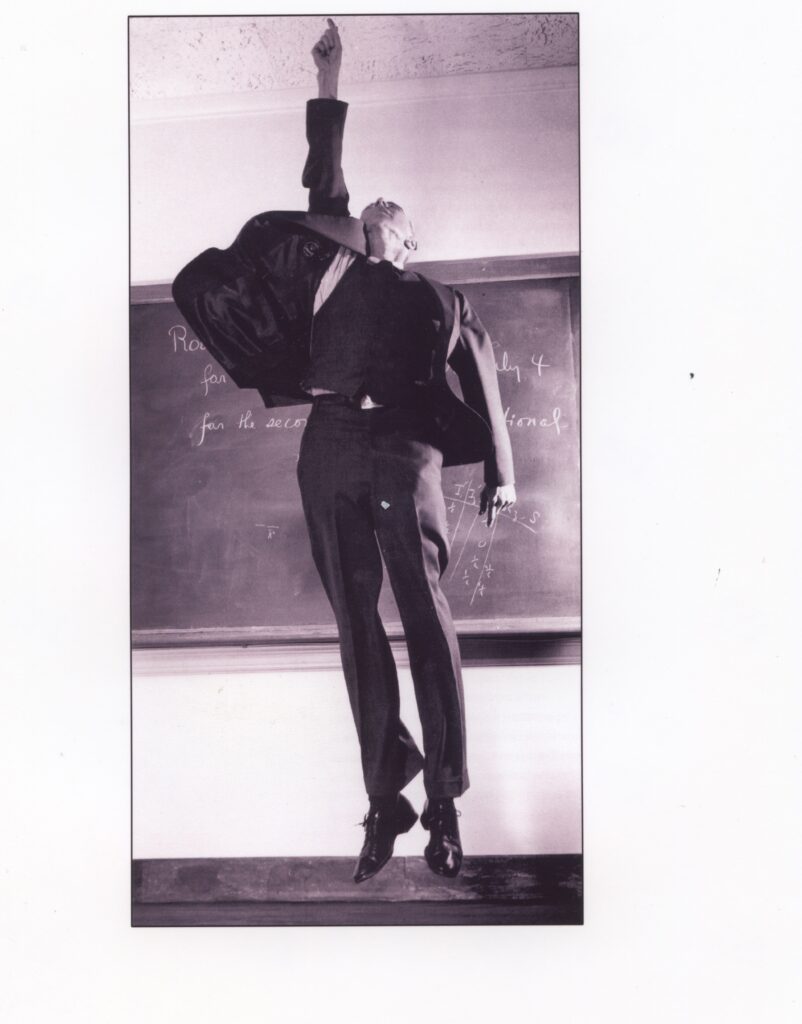

How did Berkeley shape Oppenheimer, the person?

Berkeley was incredibly important to the transformation of Oppenheimer, and Oppenheimer was incredibly important to the transformation of Berkeley.

The curious thing about Oppenheimer is he came from a wealthy uptown New York family very well treated by capitalism. He got to Berkeley and became politically aware around the time of the great longshoreman strike, when migrant labor was organizing. That changed him and got him incredibly involved with what we now call progressive causes.

A good friend of his told me when Oppenheimer came to Berkeley, it was the first time in his life he learned to eat really well – a common triumph for those of us who come here.

What about Oppenheimer stood out to you?

The absence of any imagery of what happened on the ground in Hiroshima surprised me. That’s not an accident. The filmmakers have good reason to do what they did. (Ed. Note: Nolan explained that, since the movie tells the story largely through the perspective of Oppenheimer, who did not witness the actual bombings, it was decided to leave that footage out of the film.)

When I did The Day After Trinity, film footage from Hiroshima had just been declassified in 1979. Within hours of the bombing, a Japanese film crew was on the ground filming the victims, and that footage was seized and sequestered by the United States Army. We felt if the point of nuclear weapons is that you should never use them again, the imagery of Hiroshima was the best illustration of why not to.

Did you see any glaring inaccuracies in Oppenheimer? Do they matter?

There are tons of minor things that never happened. Like did Oppenheimer actually climb to the top of the tower? Or did he just go to the base of the tower? Or did he climb halfway up?

There’s no question this version of Oppenheimer and the story of the nuclear Garden of Eden is the story [that will be] locked in the public imagination for some time to come.

Oppenheimer has flown away into mythology. We can have a discussion about whether the detail accuracy of the story matters. Or is it the image of Oppenheimer now lodged in the global imagination that matters?

Elena Cavender is a Technology and Culture reporter at Mashable where she covers digital trends and TikTok. She graduated from UC Berkeley in 2021.