Barbie’s pink heels took the world by storm this past summer. The biggest box office hit of the year, Greta Gerwig’s Barbie raked in $1.3 billion, becoming one of the only female-dominated casts to rank in the top 20 highest grossing movies of all time.

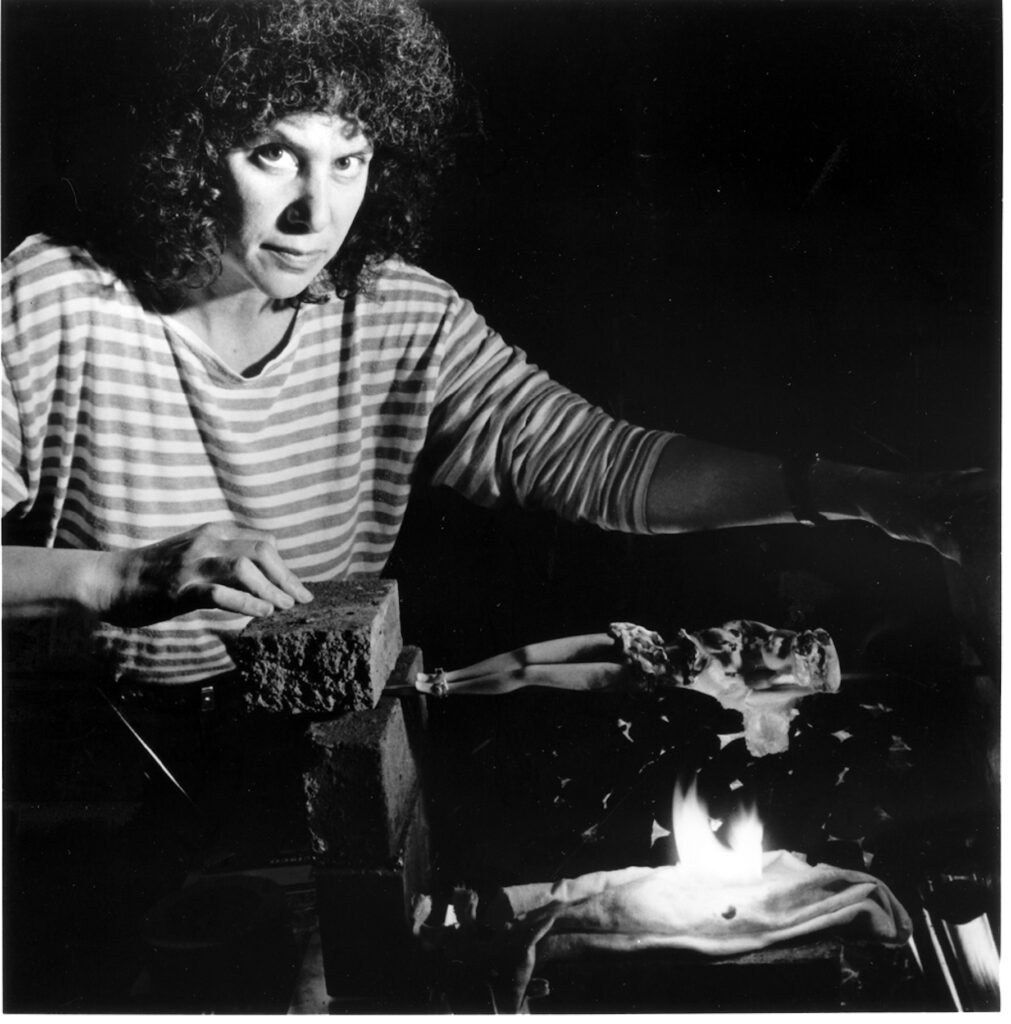

But long before Margot Robbie entered the Barbie Dreamhouse, another Barbie movie had attempted to tackle the cultural phenomenon that is Mattel’s tip-toeing doll. Barbie Nation, produced by Berkeley alumna Susan Stern in 1998, was the first to show our tumultuous relationship with the doll heralded as both a feminist icon and the complete opposite. In the documentary, Stern explores Barbie Jesus worshippers and Barbie fetishizers, fanatical Barbie collectors and Barbie body dysmorphia protesters.

Twenty-five years after the film’s debut, California sat down with Stern, B.A. ’74, to chat about her own Barbie story, what the doll means to her and society, and why Barbie is so pink. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with your own Barbie story. How did you come to this subject?

I was born in 1953. The first Barbie came out in 1959, so I had her. I was a Barbie defiler from the beginning. I was right in tune with Greta Gerwig’s “Weird Barbie”: I cut the ponytail off my 1959 Number One Barbie, and it turned out the hair was only rooted along the sides of the scalp, so her hair just fell down in front of her face and she was completely bald. That was shocking and horrifying.

I don’t really remember playing with her after that, or thinking about her very much, until I had my own daughter when I was 35. I never bought my daughter a Barbie doll. I was, and still am, a feminist, but my philosophy of parenting and life is not to ban things. So it never occurred to me to prevent my daughter from having a Barbie. I think it was a cousin that gave my daughter the Barbie doll and then, as I like to say, you put them in a closet, you open the door, and suddenly you’ve got 20 of them. They breed.

My daughter, Nora, wanted to play this game called “Jealous Barbie” [in which] one Barbie would be jealous of another Barbie. And so, of course, I gave her the feminist lecture: ‘Women don’t have to be jealous of other women.’ And then that’s when she gave her great line about tolerance: ‘Mom, why don’t we first play what I want to play, and then we can play what you want to play.’ So my late husband and I played Barbie with her. We all made up these really weird Barbie doll games, and when I talked about this to other people they started telling me their Barbie doll stories—and each one was weirder than the other.

By this point, I had become a journalist after [completing] my degree [in journalism] at UC Berkeley. I was in the broadcasting program at City College in San Francisco, and I had this idea to make a film about Barbie. No one had made a documentary about her. I asked Mattel and they said, ‘No, not only are we not making any films about Barbie, you’re not going to make a film about Barbie either because Barbie is this sacred ideal. You can’t put a face on her and you can’t put a story behind her because she is just this blank slate for children to project their dreams on.’

Of course, the rest is history. I made my film, and they now made their film.

The first scene in your movie says, “What follows is not authorized by Mattel.” How did that go over?

Mine was definitely not authorized, and I was afraid. Barbie Nation documents that, in the 1990s, Mattel was suing [over intellectual property]. They sued Aqua (the group behind hit single Barbie Girl), they sued all sorts of people who were making satires about Barbie and people that were part of the huge Barbie fan world. I was afraid they were going to sue me.

But then I ran into Mattel people at one of these unauthorized conventions that the Barbie fans put on, and we just hit it off. They started cooperating with me, to the point where they sent me the reel of old Barbie commercials. I couldn’t believe it.

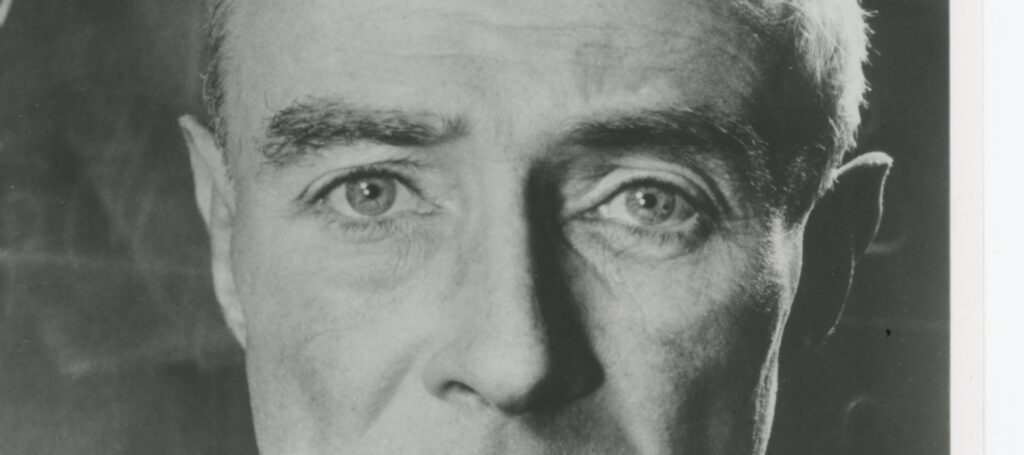

I got it in writing that they were giving me this reel, and they were allowing me to use it. They allowed me to come to the Mattel headquarters and interview their PR people. I tried to get an interview with Ruth Handler (the inventor of Barbie) at a convention she was appearing at, and they said no. I said, ‘Okay, well, can I walk along with Ruth when she goes from one interview to another and film her doing it?’ They said, ‘Sure.’ And then [her scheduled interview got] canceled. So I got the interview and we really hit it off. She invited me back to her penthouse in L.A., and that’s how I got the incredible interview with Elliot Handler, Ruth, and Barbara Handler, her daughter.

You started out as a Barbie defiler. Did your feelings change while playing with your daughter or while making the film?

Nora once said, ‘Mom, you’re infected with the disease of sexism, just like we all are.’ I think that’s true. I didn’t worry specifically about Barbie giving my daughter an unrealistic sense of body image and beauty because the whole culture gives you a distorted sense of body image and beauty. There’s no escaping it. I think you just have to learn to ridicule it. In Nora’s Barbie play, we never took it seriously. There was always this tongue-in-cheek element to it.

In your film, Ruth says that Barbie was supposed to be plain. But now, Barbie’s all pink.

It’s true—if you look at that 1959 Barbie that I had, she has serious side-eye. She’s not pretty; she’s kind of scary looking. And she didn’t wear any pink.

My theory is that she became steadily pinker at the same time that she was put into more male- dominated fields. So as she was allowed to become an astronaut and a politician and a doctor, she also became pinker. It’s almost a way of making her less threatening as she takes on male-dominated occupations.

How did all of this coalesce into a theme for the documentary?

The message for me was and remains the power of creativity and the fact that human beings can make, from the most manufactured of things, a life that is unique. To me, that message is even more important now when we’re confronting AI. What’s going to be left to being human? Though I know that AI can be programmed to make all sorts of interesting art, I do hope something remains special about human creativity.

Do you see value in turning Barbie into a major motion picture?

I loved Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie. I think it’s a powerful feminist movie disguised in pink fluff! I mean, friends my age were saying to each other, ‘Man, can you believe we didn’t know that you can say the word patriarchy without wearing overalls?’ It seemed so radical to say the word patriarchy, and Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie made it okay.

And I thought it was a really deep movie. I mean, this movie ends on the idea that to be human, which is better than being a doll or a machine, you have to face uncertainty.

There are a lot of people who say that this is a big brand opportunity for Mattel. I’m actually curious if that will turn out to be true because it was so much a film for adults. I don’t know yet whether it’s going to result in a lot of sales. Yes, it was a marketing opportunity, but I think it’s important to know that all of culture is a marketing opportunity. It’s probably most insidious when you don’t think you’re being sold something. Our culture is always selling you something.

Barbie Nation is available for purchase or rent on Amazon Prime, Apple TV, and YouTube. Barbie is expected to hit Max this month.