Older than Red State versus Blue State, older than the Montagues versus the Capulets, humankind’s primal combat is the age-old conflict between the Night Owls and the Early Birds.

Night Owls, of whom (full disclosure here) this writer is one, are sophisticated folks who believe the pleasure of staying up late is exceeded only by the pleasure of sleeping in the next morning—or the next afternoon, if it comes to that. Their hero is Elvis Presley, who famously said, “The sun’s down and the moon’s pretty; it’s time to ramble.”

Early Birds are masochists who for some unfathomable reason think a sunrise is one of life’s great experiences. (I wouldn’t know because I’ve never seen one.) At the helm is Benjamin Franklin, who famously said, “Early to bed, early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.”

Passage of the ballot measure, Proposition 7, would be just the first step in what even Brown admits is “a circuitous process” to abolish Daylight Saving Time.

This venerable conflict comes to a head twice a year: on the second Sunday in March, when Daylight Saving Time (note: not “Daylight Savings,” which sounds like a small bank in Pacoima) goes into effect, the clocks “spring forward,” and Night Owls everywhere go into mourning; and the first Sunday in November, when the clocks “fall back” and the Early Birds are forced to suffer through another hour of night.

But it’s hardly a fair trade-off because, as even self-confessed early bird Benjamin Smarr, a post-doctoral fellow in psychology at UC Berkeley and an expert on sleep and circadian rhythms, admits, “It’s easier to sleep in an hour later than get up an hour earlier.”

Daylight Saving Time, which was originally instated to prolong evening daylight during the summer months, has long been a subject of debate. In California, it’s now up for a vote.

Update: Since this story was first published, Proposition 7 has been passed by California voters.

On June 28, California Governor Jerry Brown attempted to end this biannual confusion by signing Assembly Bill 207, which places an initiative on the November ballot that would allow the state to cancel Daylight Saving Time for good. As an extra flourish, the governor added to his signature the words “Fiat Lux!” (Latin for “Let there be light”), which happens to be the official motto of his alma mater, UC Berkeley (Class of ’61). Coincidence? You judge.

Hypothetically speaking, passage of the ballot measure, Proposition 7, would be just the first step in what even Brown admits is “a circuitous process” to abolish Daylight Saving Time. A lot of hoops have to be jumped through first.

For starters, if passed, all Proposition 7 would do is repeal an earlier ballot proposition, passed in 1949, that established Daylight Saving Time in the first place. Then the matter would go back to the legislature to pass new legislation—and by a 2/3 vote, too, no easy thing—to end Daylight Saving Time. (This cumbersome procedure is necessary because, constitutionally, a legislature can’t repeal a ballot measure. Only another ballot measure can.)

What about Arizona and Hawaii, who have been happily on permanent Standard Time for years?

And there’s still one more hurdle: The feds have to sign off, too. The federal government has its own Daylight Saving Time statute, and federal law trumps state law unless Donald Trump grants California an exemption. And he’s in no mood to do Jerry Brown any favors these days.

“I don’t know whether (my colleagues) were asleep,” state Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara), who voted against the bill, told the Los Angeles Times. “First, the federal government is going to say ‘no,’ and second, the system we have really does the best to accommodate people.”

But Assemblyman Kansen Chu (D-Milpitas), who authored the ballot measure, disagrees.

“[Daylight Saving Time] creates a lot of headaches for families when we spring forward. They have to put the kids to bed an hour earlier. Adjustment problems can last a week. My 97-year-old mom says it takes weeks for her to adapt.”

If Daylight Saving Time is abolished, what then? We’d be on the same time all year round—but which time: Standard Time, as two states, Arizona and Hawaii, already are? Or what was formerly Daylight Saving Time?

Chu says he doesn’t care; he just wants to stop switching our clocks back and forth twice a year—a practice, he says, that “negatively affects our health and safety.” He does think, however, that there would be more support for switching to permanent daylight saving time than permanent standard time.

“My sense is that people don’t mind going to work in the dark, but they definitely prefer more light after work.”

More than one way to set a clock

The same choice is facing the European Union, which received a recommendation from one of its commissions on August 31 that proposed ending DST after a survey found most Europeans oppose it. Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said millions “believe that in future, summer time should be year-round, and that’s what will happen.”

However, in a consultation paper, the commission took the opposite tack and said one option would be to let each country decide for itself whether to go for permanent summer or winter time. “That would be a sovereign decision of each member state,” Commission spokesman Alexander Winterstein explained.

“Regardless of how we name the hours, daylight time is going to get longer in the summer and shorter in the winter,” says Professor Severin Borenstein.

But it might not be that simple.

“Regardless of how we name the hours, daylight time is going to get longer in the summer and shorter in the winter,” says Severin Borenstein, Professor of Business at UC Berkeley, who has written extensively on the subject. “Everybody has a complaint about Daylight Saving Time, but think very carefully about what the alternative is. People would continue to change their schedules on their own to make better use of the daylight hours, but we’d do it individually.” For instance, Borenstein explains, “I would expect schools, stores, workplaces, etc. to start earlier in the summer months and later in the winter.” The advantage of Daylight Saving Time is that it’s “a mutual agreement that when we change the norm, we’re all going to do it on the same day; and I think that is valuable to society.”

He also sees a big downside to maintaining the same time all year round.

“The sun would be coming up at 4 a.m. in the summer, and it would still be dark at 8 a.m. in the winter, which means more sleep deprivation in the summer and more morning accidents in the winter.”

But what about Arizona and Hawaii, who have been happily on permanent Standard Time for years?

“They have the opposite problem—too much sunshine. One person I know in Arizona told me, ‘We’re not trying for daylight hours. We’re so miserable, we want some of our wake time to be in darkness, when it’s more comfortable.’ I wouldn’t take one person’s view to be definitive, but there’s certainly some logic to that.”

Meanwhile Berkeley, being Berkeley, moves to a time of its own. It’s official policy at Cal to begin all courses 10 minutes after their scheduled start time.

And there’s no law of nature that says people have to conform to the sun’s timetable.

“In China there are no time zones at all,” Borenstein says. “The country is six time zones wide, but they all run on the same time. Some people have to get up at 2 in the morning, but that’s only possible with a centralized autocratic government.

“In a decentralized, capitalistic economy like ours, the opposite happens: People keep making minor adjustments on their own.” He explains that, because the sun rises slightly later in the western end of a time zone than it does in the eastern end, people in the west tend to operate on a schedule that is about half an hour behind. “For instance, people in Michigan do things later than people in Boston.”

How does he determine that?

“Twitter data. You can see when people start tweeting in the morning, and it’s always about a half hour later in the western end.”

Meanwhile Berkeley, being Berkeley, moves to a time of its own. It’s official policy at Cal to begin all courses 10 minutes after their scheduled start time—the better to help students with back-to-back classes to get from classroom to classroom on the 1,232-acre campus.

What’s the big idea?

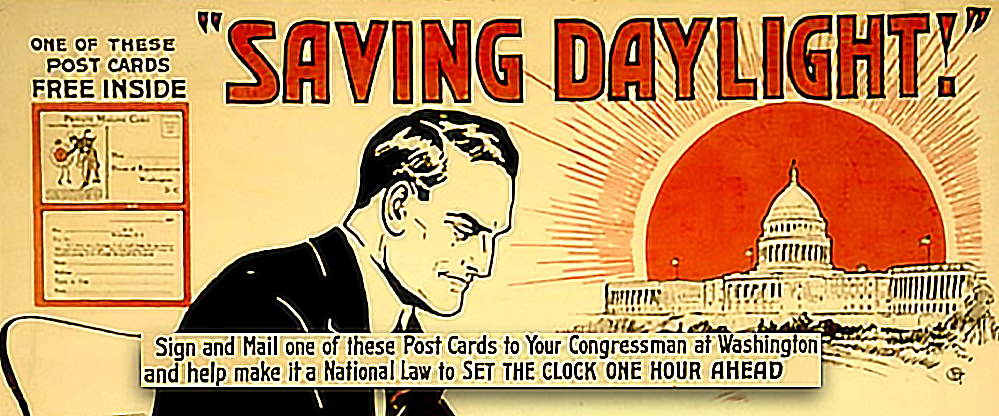

Daylight Saving Time is often mistakenly attributed to Benjamin Franklin—yes, him again—whose 1784 satirical essay advised Parisians to save money on candles by getting up earlier in the morning and taking advantage of the natural light. In fact, it was lesser-known entomologist George Vernon Hudson who is believed to have first seriously proposed the bi-annual time change in 1898, likely to get more evening daylight for his bug collecting.

But it wasn’t until World War I that DST was officially implemented. Things didn’t go so smoothly in the United States. Trouble was, DST took effect on March 31, which happened to coincide with Easter Sunday. The time switch caused a lot of people to be late to church.

Enraged evangelical preachers raised heck, blaming DST for subverting “God’s Time,” as they called it. Newspapers were flooded with irate letters from astrology fans complaining that DST screwed up their horoscopes. DST became so unpopular that Congress abolished it before it was due to expire, overriding a veto from President Woodrow Wilson.

Finally, during the energy crisis of the mid-70s, the Daylight Saving Time Energy Act expanded DST to its near-current form. But the question remains, does Daylight Saving Time actually save energy?

A 2008 study by UC Santa Barbara for the U.S. Department of Energy found DST in Indiana actually increased energy consumption in the evening by 1 percent. True, consumption for lighting was slightly down, but that was more than matched by consumption for air conditioning, which jumped by 2 to 4 percent.

According to Patricio Dominguez, an economist in the Department of Research and Chief Economist at the Inter-American Development Bank, who recently completed his Ph.D. in public policy at Berkeley, more daylight in the evening means less crime, especially property crimes—a theory he and his colleague, Kenzo Asahi, expounded in a paper titled Crime Time: How Ambient Light Affects Criminal Activity, which they presented in 2016 at the annual America Latina Crime and Policy Network Econ (AL CAPONE, for short) lunch in Berkeley.

“We studied Chile, a country that has switched on and off Daylight Saving Time many times, and we found a 27 percent decrease in robberies in the evening during Daylight Saving Time. It makes sense, if you think about it. Most robbers would prefer to operate in the dark.”

But then there’s the nagging question of what the twice-a-year time shift actually does to our bodies.

“When our circadian rhythms and sleep line up, we have better sleep and have a better day,” says post-doc Benjamin Smarr. “But when we jetlag everybody one hour, that creates sleep deprivation and circadian mismanagement, and those are bad things.”

Smarr adds, “What people who have studied this have found is that rates of automobile accidents increase on the Monday after ‘spring forward’—10 to 20 percent, depending on the study, including fatal car crashes. In the autumn, when we ‘fall back,’ something different happens. There’s a very good study out of Tennessee that found an increase in accidents, especially alcohol-related accidents, the day before the change takes effect. Because people knew they’d be able to sleep in an hour later, they stayed up an hour later the night before and kept drinking.”

Still, he cautions, it’s too early to draw general conclusions because of the relative paucity of data about DST.

And as economist Dominguez observes, this whole debate might be obsolete in a few years anyway, thanks to technology.

“Nowadays, most people look at the time on their phones,” he says. “It adjusts automatically, and they don’t realize it happened until the next day at work. They just feel a little bit tired.”