In the countdown to Sunday’s Super Bowl, suspense is building over the question on the mind of every devoted football fan: What will Marshawn Lynch say—or, more accurately, not say—to the media after the game?

However popular the Seattle Seahawks’ running back is with Seattle fans, he has a lot fewer friends at NFL headquarters, which regularly fines him big bucks for refusing to speak to reporters after games. Nor is he beloved among some segments of the press, who have called him unprofessional and immature.

But here’s the curious thing: Reporters who covered him during his playing days at Oakland Technical High School and UC Berkeley remember a very different Marshawn Lynch—one who went out of his way to be cooperative.

So what happened? The clues may lie in his odyssey from local Pop Warner ball to Super Bowl stardom.

But first, an acknowledgement that none of it really matters to Lynch’s adoring fans, who have bestowed two nicknames on him. The first is “Beast Mode,” a tribute to his hard-charging running style best exemplified by the “Beast Quake,” a game-winning 67-yard touchdown ramble against the Saints in the 2011 NFC Wild Card Game that featured nine broken tackles, a tenth tackler thrown to the ground with one arm while Lynch was cradling the ball with the other, and a crowd reaction that registered as an earthquake at a nearby seismic monitoring station.

The second is “Skittles,” after his lifelong habit of munching the tiny candies on the sideline during games. (The fans shower him with Skittles from the stands after particularly spectacular runs.)

The NFL, nonetheless, is annoyed by his refusal to play the game of publicity. It fined him $50,000 for clamming up during the 2013 season and another $50,000 this year for his no-show at the league-mandated press conference after his team lost to Kansas City—the largest fine meted out to a player since the Ray Rice scandal before the season began. (By comparison, Titans tight end Chase Coffman was fined $30,000 for running over a Ravens assistant coach standing on the sideline.)

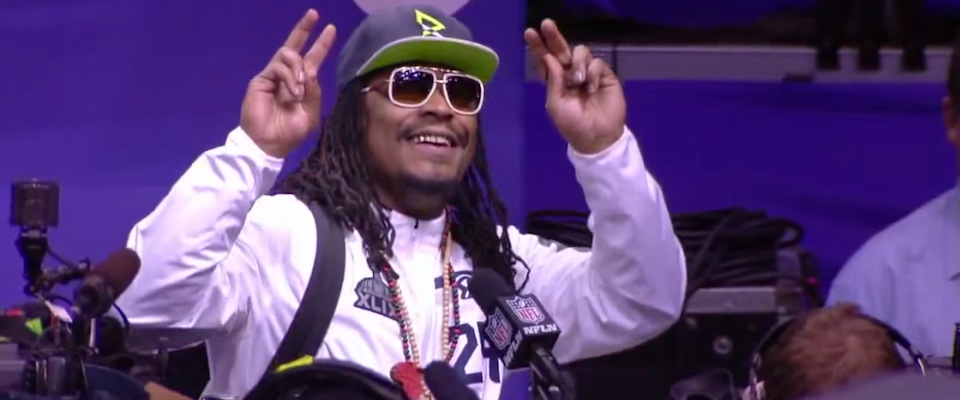

The league threatened to up the ante to $500,000 if Lynch didn’t speak to the press this past week, dubbed Media Week, so he reprised a tactic he used at last year’s Super Bowl, when he gave the identical answer to question after question: “I’m just ’bout that action, Boss.”

This year he took 29 questions on Tuesday and gave the same answer 29 times: “I’m just here so I won’t get fined.”

Then, after four minutes and 51 seconds, he announced, “It’s time,” and got up and left.

He followed that up on Wednesday with another press conference, also lasting less than five minutes. The only difference was his unvarying answer. This time it was: “You know why I’m here.”

He occasionally employed the tactic during the past season, too. On Nov. 23, after a victory over the Cardinals, he answered every question with “Yeah!” Four weeks later, after the second game against the Cardinals on Dec. 21, every question from reporters got either “Thanks for asking” or “I appreciate you asking.”

It should be noted that this routine is generally accompanied by a big, friendly smile.

By Thursday, a seemingly exasperated Lynch delivered a soliloquy to the mass of sportswriters:

“All week I done told y’all what’s up. And for some reason you continue to come back for the same thing. I don’t know what story y’all trying to get out of me. What image you are trying to portray of me. But it don’t matter what y’all think, what y’all say about me. When I go home at night to the same people I look in the face, to my family that I love, that’s all that matters. So y’all go make up whatever you want to make up, because I don’t say nothing for you to make out on. But I’ll come to your event, y’all shove cameras and microphones down my throat. But when I’m at home, in my environment, I don’t see y’all. But y’all mad at me. And if y’all ain’t mad at me, then what’ll y’all here for?

“I don’t have nothing for you. I told y’all that, so you should know that. But y’all sit here and continue to do the same thing. I’m here preparing for a game and y’all want to ask me all these questions, which is understandable, I can get that. But I told y’all I’m not about to say nothing. I’m here. I’m available for y’all. I’m here. I done talked. All of my requirements are fulfilled. So for these next three minutes, I’ll just be looking at y’all the way y’all be looking at me.”

As a result of his press performances, Lynch has no shortage of critics in the media. Philadelphia Daily News columnist Marcus Hayes wrote, “Duty should not be served. It is part of being a professional. It’s part of being an adult. Marshawn Lynch is neither.”

And the blogosphere is burning with outrage, including epithets like “thug” and worse.

But that’s not the way the reporters who covered him during his playing days at Oakland Tech and UC Berkeley, where he starred from 2004 to 2007, remember him.

“Marshawn was always approachable, always willing to talk, and always a delightful interview when he was at Cal,” says longtime Oakland Tribune columnist Dave Newhouse. “He was a solid B student who really enjoyed his classes, and a fun-loving guy. They beat Washington one year at Memorial Stadium, and after the game he gleefully drove the equipment manager’s injury cart around and around the stadium, pretending to be a ghost rider.” Newhouse admits he didn’t know the term at that time. “I didn’t understand a lot of today’s lingo, like ‘chillin,’ either, and he got a big kick out of that.”

Lynch still shows his fun-loving side on occasion, when he’s in a situation where he feels comfortable, such as last year’s Super Bowl victory parade. “He was sitting on the hood of the bus carrying the cheerleaders and throwing Skittles to everybody and just having a great time,” says Newhouse.

Herb Benenson, Cal’s Assistant Athletic Director in charge of media relations, says Lynch was a publicist’s dream when he was a Cal Bear.

“Marshawn met all our expectations for what a student athlete should be. He was a little shy, but a lot of our kids are that way. But we certainly didn’t have an issue with him. Whether it was a one-on-one interview or a postgame press conference, there was never any problem. He did whatever we asked him to do. I still have a copy on my desk of a great interview he did with ESPN – The Magazine.“

Lynch entered the NFL draft in 2007 and was picked in the first round by the Buffalo Bills. And that’s when things slowly started to go sour.

“Marshawn started off fine in his interactions with the media when he first got here,” says Buffalo News sportswriter Mark Gaughan. “He was always cooperative, always willing to do interviews. He was a little less accessible the second year, but he still did some interviews. I remember one game when the Bills played the Raiders, which had extra meaning for him, and he really opened up to me about his feelings for his hometown. His attitude started to change after a hit-and-run accident in downtown Buffalo before the ’08 season that got a lot of negative publicity. That’s when he began to distrust the media, and by the third year he was doing very few postgame interviews. By the time the 45-minute media availability period started, he’d be showered and dressed and gone.”

Lynch rushed for more than 1,000 yards during his first two seasons and became the first Bills runner to be named to the Pro Bowl since 2002. But halfway through the third season he was replaced in the starting lineup by Fred Jackson, and his season total dropped to 450 yards.

That, combined with another off-field incident in 2009, when he pled guilty to a misdemeanor weapons possession charge—a handgun in his backpack in the trunk of a car in which he was a passenger—prompted the Bills to trade Lynch to the Seahawks in 2010. And, once again, relations with the press started off on the right foot.

“My colleagues who cover the team tell me he was just fine when he first got here, no problem,” says Ed Guzman, Assistant Sports Editor of the Seattle Times. “There was no sign that he was going to shut it down. But then came that DUI arrest in 2012.”

“The arrest came shortly after he signed a lucrative contract extension, which also got a lot of scrutiny,” adds Nick Eaton, sports editor for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s website, seattlepi.com. “I think the DUI, combined with the fact that he just got his big payday, made him think, ‘Yeah, I don’t have to do this anymore.'”

“It takes five offensive linemen, a tight end, a fullback and possibly two wide receivers, in order to make my job successful. But when I do interviews, most of the time it’ll come back to me. There are only so many times I can say, ‘I owe it to my offensive linemen’ or ‘The credit should go to my teammates’ before it becomes rundown.”

“It was never a problem for us in the local media,” adds Post-Intelligencer football reporter Stephen Cohen. “But as the Seahawks rose to national prominence, the national media descended on Seattle, and they’re the ones who freaked out. That’s when the NFL started getting complaints about him.”

“It was definitely the national media who turned this into a circus,” agrees Guzman. “Our attitude is: If a guy doesn’t want to talk, there are other ways of getting the story. When he had that 79-yard run against Arizona, we wrote an oral history of the run from the point of view of everyone else in on the play. We quoted everyone but Marshawn, and it made for a really interesting story. I was very proud of our reporter, especially writing on deadline.”

But Lynch still makes an exception for reporters whom he’s come to trust over a long period of time. Newhouse is one. (“I think he likes Dave so much because they’re both Oakland guys,” says Benenson.)

The list also includes NFL Hall of Famer/NFL Network commentator Deion Sanders and NFL.com reporter Michael Silver, to whom he gave his own explanation for his recent reticence.

“I’m not as comfortable, especially at the position I play, making it about me,” he said. “As a running back, it takes five offensive linemen, a tight end, a fullback and possibly two wide receivers, in order to make my job successful. But when I do interviews, most of the time it’ll come back to me. There are only so many times I can say, ‘I owe it to my offensive linemen’ or ‘The credit should go to my teammates’ before it becomes rundown.

“This goes back even to Pop Warner. You’d have a good game and they’d want you to give a couple of quotes for the newspaper, and I would let my other teammates be the ones to talk. That’s how it was in high school, too. At Cal, I’d have my cousin, Robert Jordan, and Justin Forsett do it.”

Lynch has no shortage of defenders, either, starting with the fans, who raised the $50,000 among themselves to pay his first fine in 2013. (The NFL accepted the funds on the condition that Lynch donate $50,000 of his own money to charity.)

He also has strong supporters among his teammates, including outside linebacker Cliff Averill, who told Silver, “He’s the complete opposite of what people think. He’s a team person. He’s not one of those guys who makes it about himself.”

Backup quarterback Tavares Jackson added, “You’re gonna get the same guy every day. He’s not gonna be fake with you, that’s for sure.”

Team Lynch also includes California Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom, a diehard 49ers fan who nevertheless was at last year’s Super Bowl to cheer for his friend.

“The man’s empathetic,” Newsom told Silver. “Not long after the NFC title game [which the Niners lost to the Seahawks in a heartbreaker] he called me from his house and said, ‘Sorry, man. I hate to do that to your team.’ I’m thinking, ‘Hey! Marshawn’s a politician!’ But really, that sums him up. Even in that moment, he wasn’t celebrating or boasting or rubbing it in. He showed compassion, which is the norm for him.”

His detractors point to occasional lapses in decorum, like the two fines he received this season for grabbing his crotch after touchdowns—$11,050 during the Dec. 21 game against the Cardinals and $20,000 during the NFC title game against the Packers.

His friends just scratch their heads in puzzlement and say that’s not really him. They say the real Marshawn Lynch is the guy who flies back home to Oakland on his off day, Tuesday, and works tirelessly for charities that aid disadvantaged children, including his own foundation, “Family First,” which he runs with his cousin, backup 49ers quarterback Josh Johnson.

And students at Oakland Tech will tell you that it’s not uncommon to see a big, friendly guy with dreadlocks and a mile-wide gold-toothed smile roaming the halls, chillin’ with the students and staying and talking with them for as long as they want.

“That’s the real Marshawn Lynch,” says Newhouse. “That’s the Marshawn I remember from Cal—a very kind, smart guy who has a lot to say. It’s too bad he’s turned into a mute.”