I couldn’t decide what made me feel dirtier—looking at hundreds of pictures of naked girls, or rifling through the personal belongings of a man I’d never met. But I was doing both one evening in the Bancroft Library reading room, traversing the late photographer Charles Gatewood’s massive archive chronicling the kink, tattoo, and body modification subcultures of America and especially the West Coast.

I donned a set of purple latex gloves and delicately perused hundreds of photographs and negatives, many featuring nude people—pierced like pin cushions or covered in marinara sauce and tattoos.

There were pictures of men hanging from trees by way of hooks in the thick skin of their bleeding chests; and drag queens staring into the camera with confident gazes that seemed to demand my attention, challenge my judgment, and make me laugh. Many of the images were admittedly moving, but after the 300th or so picture of leather-clad, pierced gay men and half-naked women having food fights in bathtubs, I started to wonder why Gatewood recorded these people for five decades—and why he so proudly called himself the “family photographer of America’s erotic underground.”

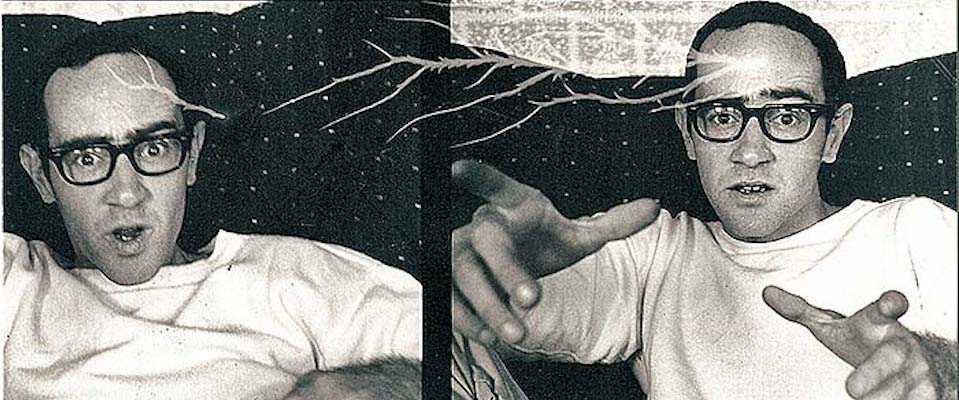

From the 1960s on, Gatewood revealed the sexual misfits and political radicals of America’s seedy underbelly. More, he was one of the only photographers continually recording the body-mod and modern primitive movements—“modern primitive” being the catchall term for those who participate in somewhat gory tribal piercing practices.

“[Gatewood] was recording that which was not recorded—this brief turning point, this period of time … where kink and BDSM—all the things under that umbrella—and modification of the body started to come out of the closet,” said Paul King ’14, treasurer of the Association of Professional Piercers and a Berkeley anthropology grad. “Before then it was all kept secret; the only facial piercing would have been a septum, something that you could hide easily. Tattoos always stopped just below the wrist. Everything had to be able to be masked.”

Despite the historical importance of the images, said Jack Von Euw, pictorial curator at the Bancroft who made the case for acquiring Gatewood’s work, there were doubts about whether the Bancroft would accept it. “How will this look? Like Bancroft Library buys pornography?!” Von Euw said. “But I think the importance of the work outweighed those considerations.”

“[Gatewood] was an explorer of human nature, an anthropologist who had great empathy for his subjects,” explained Von Euw. “I think he somehow knew he was onto something, even though a lot of people didn’t want to deal with this kind of imagery.” And so in October of 2014 the Bancroft decided to acquire the extensive collection, which had taken Gatewood five years to organize and prepare before selling. “I’m grateful that my colleagues and our director were rather forward thinking and were not so much concerned with it being offensive,” Von Euw said.

Unsurprisingly, Gatewood always struggled with presenting his work to the public as something worth studying. One of Gatewood’s favorite images is of Katy Dierlam—a 500-pound woman he photographed in the ’80s lying outside, totally naked. Gatewood had that image featured in many of his shows, and I stumbled across at least 50 reprints of it in his archive.

“He had a show at a gallery in San Diego called Rita Dean gallery in 1994,” recalled Michael Rosen, a popular Bay Area erotic photographer and Gatewood’s close friend. “They had a big print made of this fat woman—and they put the poster in the window of the gallery. And some people complained and the police came. And so the gallery people put cardboard over her nipples and her crotch. She’s so fat that there wasn’t much crotch-wise to see!” Gatewood then contacted the ACLU, said Rosen, and got the police to cease and desist and remove the cardboard.

Academia wasn’t much more welcoming—despite Gatewood’s trying to convince everyone to see his work differently.

“Even if you find it revolting and disgusting and weird and terrible, maybe some aspect of this work will help you understand something about yourself or other people,” Gatewood declared in his 1987 documentary on modern primitives, Dances Sacred and Profane.

“That’s what social sciences have always tried to be about, to explain mankind to himself, multidimensionally and cosmically and spiritually. Like really, what are we? And why do we behave the way we behave?”

“This is a man that never had to get a 9 to 5 job in his adult life. He was able to do the hustle and talk about it. When we would have conversations, he was like, ‘Yeah, you know you just gotta hustle and hustle and constantly put yourself out there.’ And then an hour later he’s like, ‘Oh my God, you’ve gotta buy this photograph. There’s only like two or three of these.’”

Gatewood was born in Illinois in 1942 to a stay-at-home mom and a traveling salesman, according to Charles Gatewood, a small book of interviews with writer V. Vale, published by RE/Search. His family moved to Springfield, Missouri, where he went to a rough, inner-city school. His parents divorced, and not long after, his father died in a hotel fire. The money Gatewood and his mother got from his father’s estate and life insurance allowed Charles to transfer to a better high school and buy his first car, a Mercury—like James Dean’s in Rebel Without a Cause.

He also soon got a stepfather who drank, and a strong desire to leave Missouri. He studied anthropology at the University of Missouri in 1960—and it was during these years that Gatewood discovered his love for photography. In Charles Gatewood, he describes climbing onto the roofs of university buildings at night to drink beer and take pictures of women in their dorms.

That was also when he met fellow photographer and student George Gardner, who at 23 had already sold Life magazine two cover photos. Gardner would later go to nine consecutive Mardi Gras events with Gatewood, sleeping rough and hanging with the no-goods and radicals who graced many of Gatewood’s books. One of the most valuable lessons Gatewood gleaned from Gardner was to “Do your own thing” and “follow your bliss.” “I wanted to be like George!” Gatewood recalled.

His admiration for Gardner also fueled the desire to be a financially independent artist: A desire that seemed to turn to obsession, as his notebooks reflect. He pasted in a series of inspirational newspaper clippings—including one on photographer William Dane, who eliminated the middle man by taking his work directly to curators.

Paul King described how that drive could make Gatewood sound like a carnival sideshow barker. “This is a man that never had to get a 9 to 5 job in his adult life. He was able to do the hustle and talk about it. When we would have conversations, he was like, ‘Yeah, you know you just gotta hustle and hustle and constantly put yourself out there.’ And then an hour later he’s like, ‘Oh my God, you’ve gotta buy this photograph. There’s only like two or three of these,’” King said, laughing. “He was constantly trying to sell.”

In the ’60s, Gatewood was traveling the world and shot his first breakout image: Bob Dylan at a press conference in Stockholm, wearing sunglasses and smoking a cigarette. The photo got worldwide syndication, and when Gatewood moved to New York he started getting regular assignments for Rolling Stone and Businessweek. He shot Allen Ginsberg, Joan Baez, Johnny Winter, Robert Palmer, and William S. Burroughs—who later provided the accompanying text for Sidetripping, Gatewood’s book showcasing everything from “Jesus freak” children to the wild streets of Mardi Gras.

One of Gatewood’s biggest regrets in life was a shot he didn’t get.

“I hate to tell the story, but I got this close to Martin Luther King,” Gatewood told Vale. “I shook his hand. I had my camera in my hand. I’m telling him how I’m an American and I’m an expatriate, and all of a sudden somebody grabs him and pulls him away and he’s gone and [whispers] I didn’t get a picture.”

His images of 1980s Wall Street were also well received—black-and-white photographs of surrealist composition. Gatewood would walk around with three cameras on his back and park himself in front of a setting he liked, sometimes waiting hours for the perfect moment: a businessman who seems to disappear into a thin stone partition, or a man in a fedora staring unfazed as a subway door appears to be about to close and crush him.

Gatewood claimed that when he photographed people, it was like he was “visiting a foreign country.” However, he was hardly an outside observer, King recalled.

“Gatewood would certainly fall into the category of a participant anthropologist,” said King. “The ‘UC Berkeley’ in me would argue he wasn’t applying any social theories, he was just recording and celebrating what got him excited and what he knew got other people excited.”

Gatewood ran a mail-order porn business called Flash Video that sustained him financially through the ’80s, and he was so well known for having sex with his models that some of them took on the title of Gatewood Girls. The first “GG” was Annie Sprinkle, a woman who would later gain notoriety as a porn pioneer—promoting sex work not just by being in porn, but by talking and writing about it. She’s known as one of the first “feminist porn” stars, and is famous for holding “Public Cervix Announcements,” wherein she would sit spread-eagled in a chair and let people examine her anatomy with a speculum and flashlight.

“We hit it off, and we had wild sex that night and became friends,” Sprinkle said of the day they first met. “He was really my photography mentor in some ways … and of course that first night we took naked pictures of each other. I don’t know if the photos came first or the sex came first—but they always came together.”

A popular Gatewood image from the ’70s is of a grinning Sprinkle in a leather cut-out bra and corset, lifting heavy dumbbells. An even more famous image is of a mostly nude, young Sprinkle posing with Fakir Musafar (referred to by many as “the Father of the Modern Primitive movement”). Sprinkle holds what appear to be two giant skewers that penetrate Musafar’s pecs, and she smiles gently into the camera.

What makes Gatewood’s archive so impressive isn’t just the work itself, but its sheer size. The collection has more than 250,000 images, including all his contact sheets and their corresponding negatives; hundreds of stock images; and giant prints of pierced genitals on sheet material. There’s a sizeable number of commercially developed pictures—images such as a naked woman squatting over a cactus, and a bald woman with birthday candles melted onto her head (I’m sure Mission One-Hour Photo had a field day developing those). There are stacks of his personal diaries, drafts of his fiction, magazines like Skin&Ink containing Gatewood mentions and features, artwork by other photographers he admired, and some of his collages. There’s also his entire personal library, with many of his published photography books—made with people like tattoo legend Spider Webb; and V. Vale, the founder of punk rock publishing company RE/Search.

To get a sense of just how massive Gatewood’s package is, pictorial archivist James Eason led me down into the depths of the Bancroft where all the archives are stored. I expected something akin to one of the musty library scenes from Indiana Jones… but it was more like that scene when they put the Ark into storage: giant warehouse-ish areas with 15-foot-high steel shelves, cool temperatures for material preservation, and wheeling industrial ladder-staircases. (“We generally like to have the students do the retrieval,” Eason said with a laugh.)

Eason showed me the Gatewood section, which has slowly been shrinking as boxes have been moved for cataloging and organization. Originally, all the work took up two sections of shelves, roughly 120 linear feet of material. When asked to forecast how long it will take before the artifacts will be exhibited to the public, both Eason and Von Euw guessed around three years.

“The average archive is 8,000–10,000 images, not 250,000,” said Eason, who went along with Von Euw to Gatewood’s home to sort through the archive. “He was a bit of a hoarder, but it wasn’t quite that bad.… It was reasonably tidy. But every cupboard was full of boxes or papers of some sort.”

One of Gatewood’s main concerns, according to Von Euw and several of Charles’s loved ones, was that his life’s work find a safe home before he died, so that it could be studied and appreciated. “I couldn’t help but think that his placing his work [at the Bancroft] allowed him, in some way, to say, ‘OK, my work’s been taken care of,’” reflected Von Euw, his eyes shining slightly with tears.

At 73, on April 8 last year, after struggling with severe pain from a degenerative disc problem, friends say Gatewood attempted to take his own life by jumping from his third-floor walk-up on Mirabel Avenue in San Francisco. He spent a few weeks in the hospital before finally succumbing on April 28.

Gatewood wrote heavily in his journals about his long struggle with depression and social anxiety. “I do have trouble relating,” he wrote in a journal entry from the ’70s. “I have to learn to walk up and say, ‘Hi, I’m Charles.’” His emotional troubles paired up with an addictive personality and led to alcoholism. Eventually, that began to affect his career.

“He missed getting several awards because he got drunk and couldn’t go to the ceremony,” said Eva Mohrman, his caretaker and girlfriend in his final days, and the last Gatewood Girl. “One time, he got drunk in Mexico with a girlfriend, and his camera was stolen. He was very horrified by where alcohol had taken him and never wanted to go back there again.”

After spending some years in Alcoholics Anonymous, he quit drinking in 1987.

“Nice to see a roomful of people who understand,” he wrote in a diary entry from his first AA meeting. “Yet I DO NOT want AA to become my identity and my entire social circuit. It’s well done, especially for a bunch of amateur drunks…. But I want to see if I can learn and receive treatment and then drop the whole frigging proposition.”

His own accounts, as well as those of friends, suggest that Gatewood continued to struggle with both addiction and emotional turmoil for the rest of his life.

Although he photographed people from all walks of life, it was with the fetish and body-mod groups in San Francisco that he finally found where he belonged.

Mohrman says Gatewood wasn’t into the pain of kink and body mod (he only had one tattoo—a single red poppy on his butt cheek). He chose the alt and fetish lifestyles for personal reasons, she theorized.

“He found out that his wife hadn’t been faithful and had kind of a secret life, and that really hurt him and left him emotionally bruised,” said Mohrman, who mainly learned about Gatewood’s ex by reading his unpublished memoir, Dirty Old Man.

“He didn’t want to forge that connection again, only to be hurt so much, so he would pay young women to be his girlfriend, and [he’d] be the sugar daddy.”

Gatewood wrote one novel, Hellfire, published in the mid-’80s, and his Forbidden Photographs includes numerous biographical moments. But much of his writing remains unseen by the public—most of it stories of sexual encounters and failed relationships, things that seemed to both enrich and plague him.

Sprinkle, like Mohrman, says Gatewood developed an obsession with pursuing young women, preferably no older than 25. In his later years, he would constantly troll Facebook for new models, and he kept lists of “hot prospects” in his journals.

“More Facebook, more adoration from fans,” he wrote in an entry in March 2011. “All this work to meet a gurl or two or three,” he writes. “But the payoffs can’t be beat…. Gulp! Calm down, Chaz!”

An entry on December 31, 2011, ends with an unattributed quote: “Only the loving find love, and they never have to look for it.”

One of the last images I flipped to was by photographer Toby Old: a black-and-white photo of a nude Gatewood standing on a floor mattress with his arms up and his legs spread. Sparkly tinsel is tied around all his limbs, and his face holds a whimsical look.

“There’s a sense of fun, a playfulness, definitely a sense of humor,” said Von Euw of Gatewood and his work. “A joie de vivre about being comfortable in your own skin…. A sense of being alive.”

Gatewood was a man willing to expose and be exposed. In his archive, his thoughts, tribulations, and philosophies seem to be laid barer than any person he’d ever photographed, like he was asking viewers not just to see his work—but to see him.

In the archive is a copy of his Forbidden Photographs. On the cover, there’s a close-up of a man holding up a fetus with a tiny heart drawn on it. I flip to the intro:

“I stand at the lectern, fielding questions. Easy questions. Silly questions. Boring questions. Then the killer: Why, Mr. Gatewood? Why are you showing us this? WHY?” he writes. “I crack a joke and give a smooth answer that says absolutely nothing. The more I explain, the less I understand. The question stays with me. It follows me. Haunts me.”

Krissy Eliot is senior associate editor of California. She previously covered the kink community for the San Francisco Bay Guardian.