Berkeley’s William Drummond talks reporting from San Quentin

In 2012, William Drummond had begun to lose faith in journalism. A changing media landscape in the age of the Internet had led to what he saw as an abandonment of the fundamentals. So when the Berkeley journalism professor was invited to teach a class at the San Quentin State Prison and become an advisor at the San Quentin News, the renowned paper published by inmates, he saw an opportunity to do something meaningful and decided to put his students to work at the paper as well. The San Quentin News Editing Project was born.

In his new book, Prison Truth: The Story of the San Quentin News, Drummond relays the paper’s history and the personal stories of the incarcerated journalists who write for it.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The San Quentin News highlights the success stories of inmates to inspire positive change in incarcerated readers. As you note in the book, that contrasts the adversarial, investigative approach to journalism that dominates in the industry right now. Was that a conscious editorial choice?

William Drummond: We don’t have that conversation with [the writers]. The paper is run through a system of self-governance. They’re the ones editing the paper. They choose the stories that they’re going to write. And they bend over backwards because in the past the warden has shut it down, and nobody wants to be responsible for doing something that would cause the newspaper to get shut down.

They wanted people to know what was happening to them in prison. Not in a sensational way. They wanted to get the story out that they had insight into what they had done, and they accepted the responsibility for that, and they were trying to work their way through that in order to become a better person. We’re there to support them and give them advice when they ask for it.

What does it feel like to operate a paper under that unspoken pressure from above?

WD: They are way more cautious than I would be. There’s an awful lot of discussion among themselves. If there’s any doubt, they go to the public information officer and bounce things off him. Most times he says, “Go ahead.” But there are some ideas I’m sure they won’t even bring up.

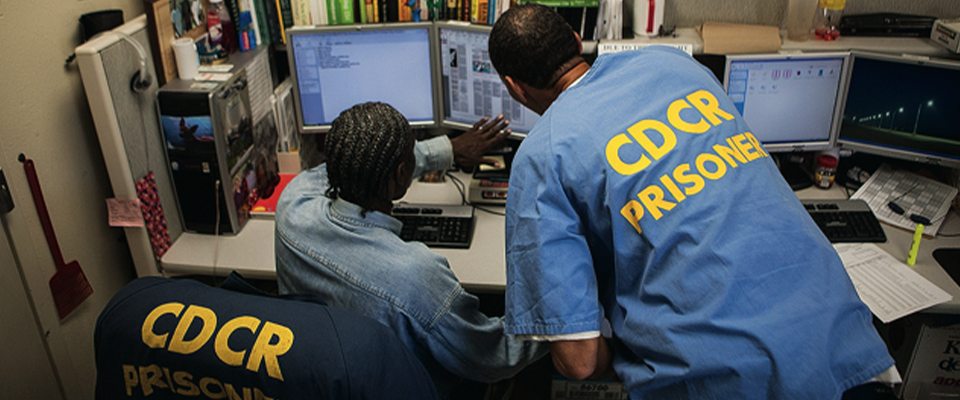

How does a newsroom operate in prison?

WD: There is a small paid staff of 12 inmates who meet every Tuesday. They have their own space in the San Quentin Media Center. They’ve got 12 computers. They get paid a dollar a day from the state like any other prison job. Then there’s a larger group of people who aspire to be staff. They’re in training and get instruction from professional journalists once a week. They learn everything you would learn in journalism school. Outside volunteers give advice on editing, which stories should go on page one, which stories are not so important.

What’s their budget? Where does the money come from?

WD: Their [operating cost] is about [$112,000] yearly. They have one paid employee on the outside who is the development director. She applies for grants, gets in touch with potential donors. Most of their money comes from the [Jonathan Logan Family] Foundation and the Ford Foundation. They also have paid subscribers [on the outside]. The circulation of the newspaper is way beyond just the people who are in prison.

What has it been like for students you brought into the classroom to help edit?

WD: They tell me they really learned a lot. Most of the men they met were old enough to be their fathers. They had been through a lot in life, and those things come up in conversation. I think there was a lot of really human interchange between the students and the prisoners.

For more, read our feature on Berkeley’s formerly incarcerated students here.

From the Spring 2020 issue of California.