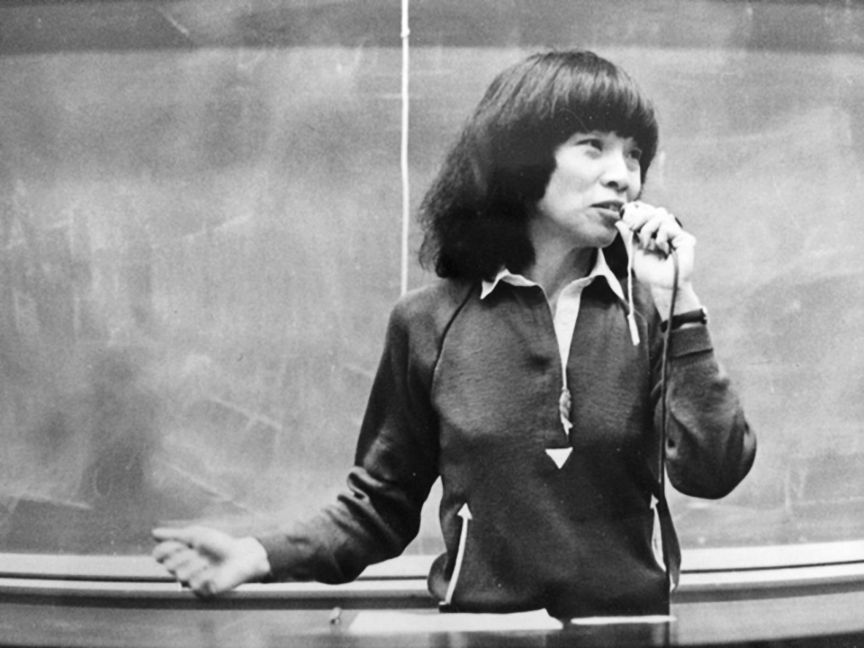

Before Elaine Kim came to Berkeley as a Ph.D. student in 1968, she was used to being the only Asian person in the room. Kim, who is Korean American, was born in New York and raised in a predominantly working class white suburb of Washington, D.C., the daughter of a migrant farmworker mother and waiter-turned-diplomat father

She would go on to be the University’s first Asian woman to get tenure and a founding member of both the Ethnic Studies Department and the Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies program.

At Berkeley, while she wasn’t alone, she didn’t feel she belonged. Non-white students didn’t see themselves reflected in the curriculum or the faculty. In 1969, Kim joined the Third World Liberation Front protests demanding that the university acknowledge the contributions of communities of color to history and scholarship. “Our motto was, ‘if something you want does not exist, you can try to create it,’” she says. The result was the founding of the Ethnic Studies Department.

It was not all roses from there. When she became a lecturer in 1971, teaching a remedial English course, she told her supervisor that policies about who would be required to take the class—which students were required to pay for but which earned them zero credits—were racist and unfair. She was fired from the program. The director’s husband told her she had “a history of deviousness.”

The questions of who is represented and how define Kim’s career. In the years that followed her academic career, she wrote books and produced films documenting the Asian American experience, whether it be in Hollywood or the 1992 Los Angeles riots in the wake of the Rodney King verdict.

Once again, as we encounter more examples of widespread Asian hate in America and find ourselves in a place to reimagine our country’s relationship to race, California magazine spoke to Elaine Kim about what we can learn from those early fights and where we might be headed.

The discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

Much of your career has been devoted to correcting representations of the Korean community and Asian American/Pacific Islanders (AAPI) more generally. What were we missing when you started your career?

In the early days, one person would be designated as the spokesperson for the entire group. So for example, after Amy Tan published Joy Luck Club, the news media asked her about Tiananmen, and then when Chang-Rae Lee wrote Native Speaker, they asked him about Korean unification because they didn’t know who to ask. So it’s a real problem for communities to have one voice represent the whole to begin with. It’s much better now.

I just asked you to speak for a very large group. I imagine that’s frustrating.

I appreciate that, but I don’t feel like I’m speaking for anybody but myself right now. Have you read that book Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka? What’s really great about that book is she uses both the first person plural and the first person singular. She writes, “We all arrived as picture brides.” She represents both their individual experiences and the collective experiences they shared with thousands of other picture brides as they disembarked from their ship to see their picture husbands for the first time. Some were really happy about it. And some were not. “I got raped on my wedding night,” “My husband was really nice to me,” “My husband was a no-show, I picked somebody else”—all these different realities under one umbrella. And I thought she was really making a comment on how you can’t have “the group is the group.”

Along those lines, what do you think about the term AAPI, as a catch-all for a really diverse group of people? Is it too big?

Politically, it has to be that way, because you can’t get anything done for Hmong people, unless they’re in a group of Southeast Asians. In that unity and with those numbers, we’re able to have more political clout. But now [people acknowledge the differences] saying, “We have a really diverse community. I’m just one person speaking.”

Did you grow up feeling represented in your community?

I grew up in the D.C. area, and schools were desegregated when I was in junior high school. My brother and I were the only Asians, I think. And then there was one Puerto Rican kid and then maybe 12 Black kids. It was very Jewish and Anglo working class. I went to the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia. I was used to being the only Asian American. They always thought I was foreign and about to return to my home country. And they said that I spoke English really well. So I was definitely made to feel like I was temporarily here. I didn’t really know that many Asian Americans until I got to Berkeley.

How did that feel to suddenly be surrounded by people who looked like you?

I looked at Asian Americans the way I think white people probably looked at Asian Americans because I was used to being the only Asian American. When I got to California, I saw all these very American [Asians]. There were many kinds of Asian Americans, including very cool ones, including really fashionable ones and ones who dressed like gangsters. I was so shocked. I felt really self-conscious to approach them. Other students have told me that, when they grew up in a totally white community and got to UCLA or Berkeley, they felt the same way. In the old days, I’d have a class that had 200 students in it, all Asian Americans, and they might have looked like they were all cut from the same cloth, but they were all different, of course. Some of them felt strange being in a whole room full of other Asian Americans.

Is this what got you interested in questions of representation?

One of the big things back in the day, was stereotyping in Hollywood. I would say very early on, everybody was interested in representation and felt the importance of films and television in our fate. And so all the students could relate to the fact that, for men, there was only Charlie Chan. Bruce Lee wasn’t even a possibility because they wouldn’t let him play in the roles. And then for women, it was just as bad—Madame Butterfly and Dragon Lady. And then there were all the faceless hordes that obey the communist dictator.

And how did you start getting into activism and community organizing?

One of the premises of [the Third World] strike was that instead of bringing education to your ghetto, or your reservation, or your Chinatown, we were encouraged to get away from those communities and live a successful life away from them. And we did not want to be educated away from our communities; we wanted to work for and in them. Many of the really important nonprofit organizations that exist today exist because of that group of people: the Asian Law Caucus, Asian Health Services, East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation.

We had the advantage of mainstream society being so shocked that they didn’t know what to do about our protests—and so we did get money to start these organizations. It’s like Martin Luther King: People think that we all graciously named all our schools and streets after him, but they forget that he was actually stabbed with scissors and spit on. They might think that all these things were granted. But actually, they were struggled for.

In response to the very disruptive student strike, the administration agreed to fund the ethnic studies programs.

We’re in a similar stage right now, where buildings are having their names removed, but it’s contentious. And it’s hard. Generations from now, people may think that it was very smooth, that it was never uncomfortable for anyone.

Or even that the university administration said, “Oh, let’s rename the buildings!”

Right. So you were one of the founders of the Ethnic Studies Department, and you’ve talked about the resistance you faced in implementing a curriculum that wasn’t just about white male scholarship. You also experienced structural and more explicit racism. I don’t know if I would have stuck around to see how things turned out, if I were you.

We were very segregated; nobody wanted joint classes with us, or joint appointments or anything. We were not asked to participate in policy planning or decision making in the university. They still thought that image from 1968 prevailed in 1990. It’s kind of amazing. But we were together. I thought the University was hostile, but Ethnic Studies wasn’t hostile. We had each other. Because of that, it wasn’t really that bad.

Going forward, will this reckoning we’re experiencing now—both in terms of awareness of anti-Asian sentiment, but also on race more generally speaking—will this stick?

I really felt with Black Lives Matter that it might be different this time. Five years ago, I used to hear comments from white women at my gym like “I don’t understand why they don’t just do what the police say?” or “Look, they’re killing people in East Oakland. I’m so glad the bad guys are killing each other and not us.” I never said anything, but I always thought, “Oh, it’s really good that I came here so I could hear these conversations.” I really do think that there are people who might not have really believed that if you’re Black and breathing, or Black and sleeping, you might get killed for that. Or just if you’re in the car, you’ve got to stick both hands out, and you’ve got to do everything you can to avoid being killed. And I think they believe it now. They believe it and they don’t like it.

There have always been lots of white students who supported ethnic studies. All along there have been allies, of course, in the faculty and also with the students. Now people are volunteering to escort elderly Asian ladies down the street. I keep seeing now that there’s more credit given to Black talent than there ever was before. That’s amazing. So I think the moment is here, again. I think that we can do it, and maybe do it better. There’s more understanding of what’s possible and what to ask for than there used to be. I think people your age are going to do it.