Danny Brown was in prison for almost two decades for a rape and murder he didn’t commit, and he has evidence to prove it: a host of eyewitness accounts validating his alibi, a polygraph test he took, and passed, at the prosecution’s request, and DNA from the crime scene matching that of another man who is currently serving time for a factually similar rape and murder.

He was released from prison in 2001 at the age of 45.

Maurice Caldwell also served more than 20 years for a murder he didn’t commit. Fifteen years after the 1991 shooting in San Francisco for which he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life, another man confessed to the crime and a judge dismissed his case for lack of evidence.

As incredible as it may seem, many exonerees are not even afforded the same consideration that most parolees receive: a change of clothes, some “gate money,” and counseling or job training. Even worse, many exonerees enter a kind of cruel legal limbo, in which, their vacated sentences notwithstanding, they are denied any official recognition of the injustice they suffered.

Caldwell was transferred from the jail in San Bruno to San Francisco, where he finally walked out on the afternoon of March 28, 2011, wearing donated clothing and carrying an envelope with $37 in it. He wasn’t sure what to do with the cash or whether to take it out of the envelope. “It’d been 21 years. I’d never touched no green money,” he says. The officers told him he could go.

Brown and Caldwell are just two in a long and growing list of Americans who have been exonerated after they were wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for many years. The story has become a common one on nightly newscasts: families tearfully reunited with long-incarcerated relatives, many of whom have spent more of their lives behind prison bars than as free persons. The moment of release is usually cast as a bittersweet vindication, justice delayed but finally served. The reality is not that simple.

In the introduction to the 2005 book, Surviving Justice: America’s Wrongfully Convicted and Exonerated, author Dave Eggers and former UC Berkeley visiting scholar Lola Vollen observed that, “The inevitable questions addressed to exonerees—‘Are you angry? Are you bitter?’—are difficult for them to answer. Often asked on the very day they are released, the day the fortunes of the wrongfully convicted turn, they are joyful, optimistic, ready to begin their lives again. But this grace period is often short-lived as the realities of their post-prison quandary become clear.”

As incredible as it may seem, many exonerees are not even afforded the same consideration that most parolees receive: a change of clothes, some “gate money,” and counseling or job training. Even worse, many exonerees enter a kind of cruel legal limbo, in which, their vacated sentences notwithstanding, they are denied any official recognition of the injustice they suffered. “After all those years, you fight and get released,” says Caldwell. “But the people who release you and let you go don’t want to say sorry or anything.”

The sentiment is echoed in Surviving Justice. A joint project of Eggers’s publishing enterprise, McSweeney’s, and the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, the book is a Studs Terkel–like collection of oral histories. One of the subjects interviewed, Christopher Ochoa, served 12 years for a rape and murder he had no connection to. He told his interviewer, “Nobody, nobody, has come out in public and said, ‘We screwed up.’ Not the DA, not the cop, not anybody. Nobody’s even apologized to me.”

The district attorney for Lucas County, Ohio, where Danny Brown’s case was prosecuted, has said that, despite his overturned conviction, Brown is still a “suspect” in the criminal investigation as a possible accomplice. She also recently told The Toledo Blade that she has “no immediate plans to retry him.” Under the laws of Ohio, Brown is entitled to nearly $1 million in restitution, but under the same laws he is unable to collect a dime as long as he is officially under investigation for any role in the original murder.

Now 60, Brown lives in a Toledo homeless shelter, broke, consumed with his case and everything that went wrong. “You been in jail all these years, and once you get out, you expected to make it,” Brown says. After prison, he did hold down a job for several years at a glass factory, but lost it during a relapse into drug addiction and depression. He says, for him, getting out of prison was like going from one cage to another, larger one.

“Once you are convicted, it’s not some tiny thing. It’s like someone threw you in a black hole and you can’t get out of it.”

False imprisonment is a story as old as incarceration itself and American legal history is studded with many famous—or infamous—cases, from the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s to more recent examples such as the near execution of Randall Dale Adams, who was exonerated after his story was told by Berkeley alum Errol Morris in the award-winning 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line. In recent decades, however, the number of people released from prison because they were never guilty to begin with has grown dramatically, in part due to the rise of DNA evidence, but also because of the efforts of pro bono groups such as The Innocence Project, co-founded by attorneys Peter Neufeld and Boalt alum Barry Scheck. These groups sift through thousands of convictions to find innocent people whom they can provide with legal help.

Scheck characterizes the work as a movement, one that is changing the way we view law enforcement, the courts and the reliability of evidence. He told the website, Big Think, “We who work within the criminal justice system, where the life and liberty of people are at stake, have to have some humility. That’s really what these DNA exonerations are teaching us.”

Today, only 30 states and the District of Columbia offer any form of compensation for exonerees, and the amount varies from as little as $50 per day imprisoned in Iowa to as much as $80,000 per year served in Texas.

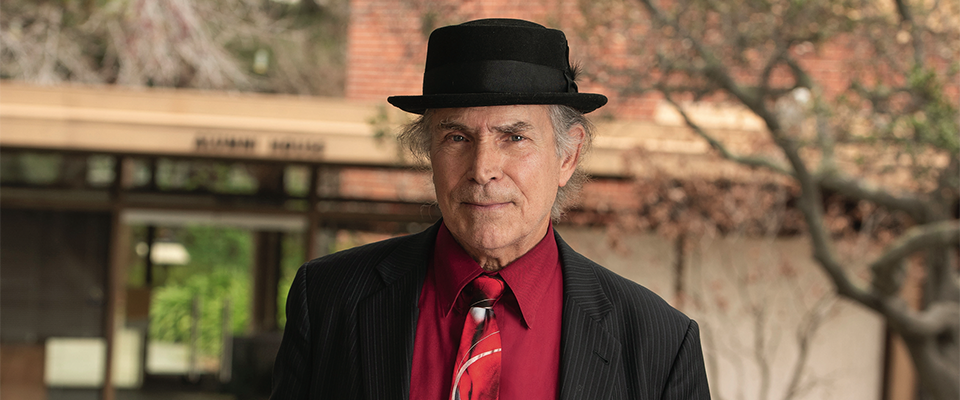

But while a dozen or so nonprofits around the country work on getting the falsely convicted out of prison, very few have the resources to help exonerees navigate the sometimes equally Kafkaesque system they’re released into. One of these is a project called After Innocence, founded by Cal history major (BA ’93) and Berkeley Law alumnus (’02) Jon Eldan. Eldan, 46, could be thought of as a roving, high-energy social worker with a J.D. A fit, clean-cut man who intensely pounds on his laptop in every spare moment, he first became interested in wrongful convictions while working as a commercial litigator at a law firm in San Francisco. He was inspired to work with the wrongly convicted by the 2005 documentary film, also called After Innocence, which profiled seven exonerees and their struggles to rebuild their lives. The film highlighted how few services are available to exonerees.

With the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, Eldan saw an opportunity to help. He pored over the regulations and mastered the application process so that he could help his clients obtain whatever health care they were eligible for—whether through the health care exchange, a job, Medicaid, Medicare or local clinics—and then help them make good use of it. He says he frequently sits with the applicant on the phone to ensure that everything goes smoothly. The process of identity verification involving past addresses, for example, is usually more complicated for Eldan’s clients because they haven’t had a “home,” often for decades.

His ambitions are intensely practical. He wants to connect people to services they are legally entitled to but often miss out on, such as health care, retirement benefits, a clean criminal record, and perhaps most importantly, restitution.

Today, only 30 states and the District of Columbia offer any form of compensation for exonerees, and the amount varies from as little as $50 per day imprisoned in Iowa to as much as $80,000 per year served in Texas. Some states require DNA exonerations or a governor’s pardon before any payouts are granted.

In California, the state pays exonerees $140 per day of incarceration, but the person must be found “factually innocent” to qualify for payment, meaning that they have to legally prove that they did not commit the crime or do anything else to cause their arrest, such as running from the police. It’s the inverse of the usual criminal case, where defendants are afforded the presumption of innocence. In determining whether or not the state owes the wrongly convicted anything, the burden of proof is shifted to the exoneree to show that he did not commit the crime.

Eldan decries the broken system and advocates for legislation to change it, but he recognizes the slow and incremental pace of change. “We have a long way to go, not just in the 20 states that offer no compensation at all, but in improving the deeply flawed compensation schemes in the other states.” Ever the pragmatist, he looks for what he characterizes as “inexpensive, simple fixes” in the meantime, measures such as providing exonerees with “an official certificate of innocence, which would help them convince potential landlords and employers of the unique injustice they suffered.”

Most of his work is done over the phone with exonerees across the country, focusing primarily on access to social services and legal assistance. On occasion, he jumps in to help with special projects. For example, when Washington State passed a law to grant compensation to exonerees who applied within three years, Eldan tracked down those who qualified to make sure they knew about the deadline. He helped four exonerees apply in time.

“No matter how many reforms we make,” acknowledges Eldan, “we will always make mistakes. Given that reality, an important measure of our fairness and integrity is how hard we look for those mistakes, what we do when we find them, and how we treat those who paid a horrible price for those mistakes.”

Such accomplishments are modest, but with the process for helping exonerees so broken or nonexistent, sometimes the only thing separating them from getting sucked back into the black hole entirely is Eldan on the other end of the line.

Last year, Congress passed a revision to the tax code that makes the money exonerees receive for their wrongful conviction tax exempt. The law also allows those who paid taxes on compensation in the past to reclaim it, but only if they file a claim by this December. Eldan is leading an effort to notify every exoneree who received compensation of the rule and is offering free assistance with filing in time.

Recently, he also started a project with law students at Boalt Hall to conduct a complete records search for exonerees and ensure that their criminal records—and the commercial background checks that are drawn from them—are accurate. The project also seeks to offer documentation of the client’s innocence as well as letters of recommendation from prominent members of the community such as state legislators, judges, and officials in order to help exonerees secure housing and employment. “This is a critical part of exoneree re-entry: getting the public to understand what happened to them,” Eldan says.

It isn’t an easy thing to do. As Danny Brown, who has had ample time to consider what went wrong in his case, says, “[The public] has an infallible faith in the justice system. Even in the face of all of these guys getting out of prison, people want to believe in the system.”

Eldan knows that some level of error is baked into the criminal-justice enterprise. The list of leading contributors to wrongful convictions is a long one, from faulty forensics to race bias, overzealous prosecutors to overworked public defenders. Such issues can be identified and addressed, but given the volume of cases, even a small rate of error will result in a large number of wrongful convictions, and, so long as we have the death penalty, even wrongful executions. As novelist and attorney Scott Turow, an adviser to After Innocence, has noted, “Law can go no farther off the tracks.”

“No matter how many reforms we make,” acknowledges Eldan, “we will always make mistakes. Given that reality, an important measure of our fairness and integrity is how hard we look for those mistakes, what we do when we find them, and how we treat those who paid a horrible price for those mistakes.”

So far, After Innocence has helped some 388 exonerees, about one-fifth of the nearly 2,000 individuals in the National Registry of Exonerations, a database maintained at the University of Michigan of people exonerated in the United States since 1989. Other organizations have reached only a fraction of that number, notes Eldan, a hint of pride in his voice.

After Innocence, which has received support from individual donors and foundations, including the Reva and David Logan Foundation (which sponsors an annual investigative reporting symposium at the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism), takes charitable contributions through its 501c3 fiscal sponsor, the Althea Foundation. Eldan tries to keep the operation as lean as possible. There is no office, nearly all the work is done by phone and Internet, and it has hardly any costs other than staffing. He worked as a full-time volunteer to get the project off the ground, and is now raising money to keep it going and expand the number of people he can reach.

Even those he does reach often continue to struggle.

Like Danny Brown, Maurice Caldwell has been unable to get compensation from the state because, despite the lack of evidence against him, he hasn’t been able to meet the required standard to show his innocence. The original eyewitness who testified against him is dead. Like Brown, he is also penniless and dependent on Social Security benefits. He still struggles with the physical effects of prison: While working in the kitchen he suffered back injuries for which he received inadequate health care. He had trouble with his teeth but had never been to a dentist on the outside before. Eldan helped. He filed for Social Security, set him up with health care, and arranged a dentist appointment.

To Caldwell, Eldan is a hero. He compares him to a sighted person helping the blind. And while no one from the system that put him behind bars has ever apologized to him, Caldwell says Eldan sat him down and said, “Man, I’m a part of the society, and I know what was done to you was wrong. I can’t rectify the wrong, but I can help you get established.”

This past summer, Danny Brown came to the Bay Area to participate in a restorative justice event with the Northern California Innocence Project. Joining ten other exonerees, he opened up about the pain he had experienced as a result of his ordeal. It meant a lot to him just to be able to talk, and he thanked Eldan for making the visit possible.

“Jon let me be a part of that. I didn’t have no money. They paid for me to come there. Jon picked me up. That was important to me. That’s important when you are going through something like a wrongful incarceration. It’s like being a prisoner

of war.”

Jessica Pishko is a freelance journalist covering the criminal justice system. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, and other publications.