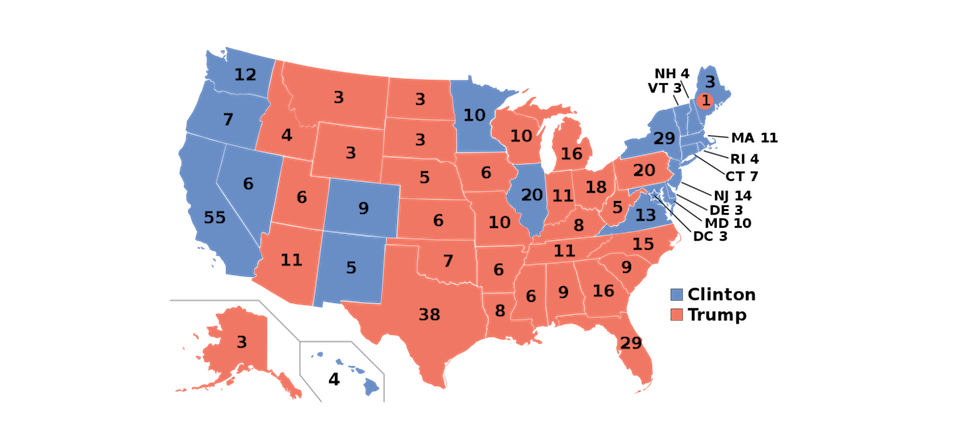

It’s no secret that things started going sideways for the Democratic Party long before November 8. In 2009, the Democrats had a lock on both federal legislatures, with 257 seats in the House of Representatives and 57 in the Senate. Following the 2016 election, those numbers had plummeted to 194 House members and 48 senators.

At the state level, Democrats have 10 fewer governors than they did in 2008, dropping from 28 to 18. In 2008, Democrats held both legislative chambers in 28 states and shared legislative control in eight states, while Republicans held both chambers in only 14 state legislatures. Jump to 2015: Republicans controlled 30 state legislatures, while Democrats held on to eleven.

Clearly, something has gone awry with the Democratic long game. And after the recent election, it seemed that new strategies—and new blood—were in order. That was particularly the case for the House of Representatives, a hotbed of partisanship (at least when compared to the relatively genteel Senate) and a testing ground for both new personalities and new ideas.

It was deflating for some party activists when the House Democratic caucus reelected Nancy Pelosi as minority leader on November 30, rejecting challenger Tim Ryan of Ohio. For many Democrats, Ryan seemed just the tonic the party needed. He was young, from a Rust Belt state, and representative of the white working class voters who had drifted from the Dems in the last few election cycles and ultimately handed Trump the presidency. Pelosi, of course, is deeply beloved in her San Francisco-centric district, but in few other places. Indeed, she is largely despised in Flyover Country as an aged and out-of-touch limousine liberal who promotes ultra progressive ideals, simultaneously hobnobbing with the moneyed and powerful while spurning the suffering hoi polloi.

It was deflating for some party activists when the House Democratic caucus reelected Nancy Pelosi as minority leader on November 30, rejecting challenger Tim Ryan of Ohio. For many Democrats, Ryan seemed just the tonic the party needed. He was young, from a Rust Belt state, and representative of the white working class voters who had drifted from the Dems in the last few election cycles and ultimately handed Trump the presidency. Pelosi, of course, is deeply beloved in her San Francisco-centric district, but in few other places. Indeed, she is largely despised in Flyover Country as an aged and out-of-touch limousine liberal who promotes ultra progressive ideals, simultaneously hobnobbing with the moneyed and powerful while spurning the suffering hoi polloi.

So did the Democrats just shoot themselves in the foot by sticking with Pelosi and rejecting Ryan?

“It’s fair to say Pelosi has some liabilities,” says UC Berkeley political science Professor Eric Schickler, an authority on congressional intrigues and machinations, “and it’s natural to see some disaffection with a House leader if things for [her] party aren’t going well. And it’s also true that some of that disaffection is probably generational. Ryan is young, and that’s appealing to caucus members and party activists who aren’t part of the old power structure.”

That said, Schickler observes, Pelosi was able to make a pretty sound case for retaining her position. First, she represented continuity. In the aftermath of the November election, Democrats were disinclined to hand off the helm of their battered ship to an unknown quantity, no matter how charismatic.

“She’s also a proven fundraiser, and that talent is particularly important for the Democrats right now,” Schickler says. “And she’s been doing some things to spread power around the caucus in an attempt to diffuse some of the concern, like creating new positions. It doesn’t look like she’s trying to concentrate power. She seems to be trying to ensure more people get to sit at the table.”

Still, observes Schickler, about a third of House Democrats voted against Pelosi, a strong indication that she was not given carte blanche.

“The fact that so many people opposed her indicates that she does have a problem,” Schickler says. “When your party has had repeated setbacks and can’t regain the majority, your members are going to get restless. This was a warning shot. If she can hold things together and there’s some improvement in the next few years, okay. Otherwise, there’ll likely be another challenge.”

“…frankly, the incentive for complete opposition is strong.”

Also, says Schickler, Democrats have larger issues to address than the leader of their congressional caucus. Most pressingly, they need to collectively determine an effective strategy for the next four years.

“The significance of party leadership is often over-exaggerated, especially for minority party leaders,” says Schickler. “[The Democrats’] big problem will be figuring out how to deal with the Trump administration—whether they cut deals with him on issues of mutual interest such as infrastructure, trade and jobs, or whether they opt for all-out opposition. And frankly, the incentive for complete opposition is strong. The Republicans have been doing it since 2008, and it turned out that it was in their interests not to compromise, not to make deals. That wasn’t necessarily best for the country, of course. But for them, it worked.”

Finally, it may be a bit premature for Democrats to sink completely into the Slough of Despond. What goes around comes around, and that’s particularly true for politics. The 2018 and 2020 elections might go well for the Dems; not so much because of whom they’ll support or what they’ll do, but because of what Trump may end up doing in the interim.

“A lot can happen in two years, let alone four,” says Schickler. “After the 2004 election, a lot of people thought the Democrats wouldn’t win back the House for a very long time. [They took it back in 2006.] The Trump victory could give Democrats some real opportunities for midterm gains in both the House and state legislatures in 2018. If they do that, they could be pretty well positioned for 2020.”