On June 24, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, reversing 49 years of constitutional protection for abortion. As of this writing, 14 states have near-total or total abortion bans, and it is expected that about half of the country will either ban or limit access to the procedure. Regardless of your position on the issue, everyone can acknowledge that this is a pivotal moment in American history that will have a profound effect on the lives of countless Americans. The implications of the decision extend beyond abortion into issues of privacy and marriage equality and access to contraception. At California, we wanted to know what a post-Roe future might look like. We turned to Berkeley experts to ask about the consequences of this decision, what it reveals about the changing nature of the court, and what lawmakers are likely to do next.

Becca Andrews, M.J. ’15, is a journalist who covers reproductive justice, gender, and evangelicalism. She is the author of No Choice: The Destruction of Roe v. Wade and the Fight to Protect a Fundamental American Right.

Christine Henneberg, M.S. ’11, a graduate of the Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program, is a first- and second-trimester abortion provider in California. She is the author of the memoir Boundless: An Abortion Doctor Becomes a Mother.

Alexa Koenig, M.A. ’09, Ph.D. ’13, is the executive director of Berkeley’s Human Rights Center and a lecturer at the law and journalism schools. She was part of the Berkeley team that worked on the Reveal podcast episode “A Strike at the Heart of Roe.”

Mini Timmaraju ’95 is the president of NARAL Pro-Choice America. She has more than 20 years of experience leading federal, state, and local campaigns, as well as advocacy efforts around reproductive rights, gender justice, and racial justice.

Whom will Roe being overturned affect most?

TIMMARAJU: Rural Americans, people of color, communities that are traditionally disenfranchised and have challenges accessing health care. Immigrants, folks with limited English proficiency, and LGBTQ folks. Trans men. So all the communities that are the most vulnerable in our health care ecosystem will be the most impacted. Those of us who have access to resources, we can probably get to another state to access.

ANDREWS: There’s a huge overlap between people who don’t get abortion care and those who struggle to get basic health care and reproductive health care.

HENNEBERG: I would emphasize that women who can travel to another state for an abortion are, relatively speaking, very lucky. And they are very safe. If they’re traveling to California to have an abortion, they are among the luckiest. They certainly have worries. But my big-picture worries are for the women who can’t travel. There are people who don’t have access to the internet, who don’t have a mailing address where they can receive secure mail, or who just don’t have anyone in their life who is going to support them and keep them safe. I think about teenagers. Or people who don’t have money to even pay for [abortion] pills over the internet. Or women in an abusive relationship. Or an undocumented person who may have trouble using the internet or getting mail delivered to them. These people would have had difficulty accessing abortion to begin with before Roe got overturned. I already, even in California, look at some of my teenage patients and I think, “How, but for the grace of God, did you find your way in here?”

What could be a consequence of this decision that people haven’t thought of?

KOENIG: I think the question is going to be how far this particular decision is extended. Certainly, if a right to privacy is eviscerated, which has been one of the underlying concepts of later jurisprudence post-Roe, you could see the erosion of any other constitutional rights that are based on this notion of privacy. So, issues like the right to access to birth control, issues like the right to marry the person of your choice, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, etc., all of that is protected currently by this notion of a right to privacy being in the Constitution, but not necessarily being expressly stated. And so, if we do see a Supreme Court that is saying that the only rights we will recognize are those that are explicitly stated or that the original drafters would have recognized, I think we see an entire sweep of potentially progressive issues and rights that may become debated. That’s something that has many of us very concerned.

“I THINK WE’RE ALREADY SEEING THE BEGINNING OF A DEATH BY A THOUSAND CUTS.”

alexa koenig

TIMMARAJU: When you ask Republican extremist legislators on the ground and in key states, like in Mississippi, they’re saying everything’s on the table. So once you lose the court’s protection, and it gets into the hands of legislators, state by state, it’s like wildfire. So we have to be vigilant.

ANDREWS: I’m curious to see how this is going to affect things like in vitro fertilization. Are we going to see new laws regulating what happens to fertilized embryos that are kept at labs? And the suggestion has been raised that people who are putting in data into fertility trackers or period tracker apps, that that could be taken by the government and used to prosecute someone. I think we’re on a clear path toward criminalizing pregnancy outcomes.

HENNEBERG: I’m concerned about how this will affect our ability to hire diversely, which is already a weakness of the field of abortion care. In California, we have a patient demographic that looks like [the demographics] of the state. So we’re seeing a lot of Black and Brown women. And we don’t have a workforce of abortion providers who look like them. And as much as I think I’m pretty good at establishing a rapport with my patients, there are plenty of patients where I think, “I wish you didn’t have to have me as your doctor. I wish you could see someone who looked like you and who you would likely feel more trusting of.” And I think [the end of Roe] is going to make that even harder because so many of the barriers that exist to working in this field are only going to intensify when the work is criminalized in half of the country. It creates an even more intimidating environment for a person of color to sign up to work in.

Can you describe the toll that getting turned away for an abortion or struggling to find access takes on individuals?

ANDREWS: Researchers at UCSF have this study out called the Turnaway Study that analyzes the long-term impact of being turned away for an abortion on people. They saw really severe mental health consequences, less economic mobility and opportunity. I keep thinking about this woman in Alabama. She’s a Black woman and struggled her entire life to get reproductive health care and to get diagnosed for fibroids. She desperately wants to have a child and to be a mother. But the pandemic came, and she lost her health insurance and lost her job. And she winds up pregnant. And it was so wrenching for her to be like, I want this pregnancy and I want to have a baby and I’m not in a position to raise a child the way that I would want to and I don’t want to put this kid through uncertainty and I don’t want to not be able to support it. So she came in, in Tuscaloosa, to have an abortion, and just having to go through that and walk past the protesters that are yelling at her that Black lives matter was just heartbreaking for her. After Texas banned abortion as well, there were a lot of people who had traveled. I saw folks in Wichita, Kansas, and Huntsville, Alabama, in Memphis, Tennessee, who had traveled and were just exhausted. Abortion is a medical procedure. Ideally, you want to arrive and be well rested and nourished. And these are people who had been on the road, eating fast food, and trying to make things work financially. It’s not how you want to go in for a medical procedure.

Will people who live in states where abortion remains legal be affected?

HENNEBERG: I think that the ripple effect will certainly penetrate into the minds and the realities of the women I see in California. I am concerned about bottlenecks of care. I also hesitate to go there because I think that’s a problem of privilege in a state where you can at least legally access abortion. Are we going to be overwhelmed by people coming from out of state? It seems hard to predict. And it’s certainly hard to imagine that we’re prepared for it, if it does happen. I think it’s easy to say there’s lots of people who are qualified to provide abortions. But you need the staff and the facility. You don’t just need a doctor who’s able and willing. And nobody can hire anyone right now, in any field. Just like in a restaurant, our patients are walking into the clinic and being told, “We’re so sorry for the additional wait times. We’re very short-staffed.” I don’t know how they’re going to staff an extra abortion clinic if they need one.

TIMMARAJU: [States such as] California will take in an incredible number of incoming patients from around the country. And that’s why California is being so smart and thoughtful about expanding access and resources, but probably it will not be enough because the need will be overwhelming. In California, we are already seeing patients from places like Texas and Oklahoma. I would go back to how many people don’t understand that if Roe doesn’t fall in their state, that doesn’t mean they’re not under threat. A national abortion ban is possible. We’re seeing more and more cases, including in California, of folks being prosecuted or investigated for a miscarriage.

How likely is a national ban?

KOENIG: The majority of the American people don’t seem to support an abortion ban. They want limits to access to abortion. So I don’t see a national ban coming anytime soon. Regardless of what we’re seeing in the Supreme Court, we do have three different branches of government. But I do think we’re going to continue to see a chipping away at people’s access to reproductive support. I think we’re already seeing the beginning of a death by a thousand cuts. And this will disproportionately hit those with the least access to resources, the most vulnerable, the youngest, etc. The very people who need the most support in moments like this.

TIMMARAJU: Mitch McConnell and House and Senate Republicans have indicated a strong interest in pushing and pursuing a national abortion ban. I think we’re going to see a very challenging election this November. And if we have a loss of the House, we most definitely believe a national ban is on [Republicans’] agenda. There will be some legal questions around how that affects states with constitutional guarantees. Opponents to abortion access are feeling incredibly emboldened. And we don’t have a single, truly pro-choice Republican left in the House or the Senate.

ANDREWS: The Republican Party has such a stranglehold on the federal government at this point. The Supreme Court has always been the check for that. We talked about checks and balances, and in the United States, now there isn’t one. So I definitely think it would be foolish to consider that an impossibility.

What about efforts to make abortion a criminal offense?

KOENIG: Unlikely, but definitely a risk. That said, I think that if we’ve learned anything over the last decade, it’s not to let our guard down and take rights for granted. With the authoritarian turn that we’ve seen a lot of democratic nations make, I think we are as vulnerable to that as any other country. And we have to safeguard against the potential for a slippery slope. So I do think, in terms of abortion becoming a criminal offense, we’re likely going to see that succeed in at least a couple of states and certainly be attempted in many states across the United States. But even if they lose, it’s an intimidation tactic. It’s sending normative messaging that if you’re trying to end a pregnancy, that’s wrong and should be thought of as a criminal act. And so the psychological warfare or the psychological burden that imposes on women is just added on top of the economic burden and the physical burdens that individuals are already having to bear.

How will this affect abortion providers?

ANDREWS: To the Texas example, I was talking to an abortion provider who had a patient with an ectopic pregnancy [when a fertilized egg grows outside the uterus, which can be fatal for the pregnant person] and she was not able to get an abortion for the ectopic pregnancy in Texas because the law is so fuzzy and doctors are terrified to do anything that’s going to get them arrested. I was talking to a man who was an abortion provider in Knoxville, Tennessee, who recently testified before the Tennessee legislature because we had a six-week ban, a copycat of the Texas law, come in front of the legislature. He was talking about how that really interferes in a physician’s ability to do what’s best for a patient. Having to think about the law and having to think about potential legal consequences is inherently incompatible with patient care.

HENNEBERG: As long as we maintain a Democratic governor in California, I’m not worried about being criminalized for my work. But there’s a way this is already showing up [in California]. An example is when we do have patients come from Texas, I will often answer calls from clinicians who are seeing them, and more than once in the last couple of weeks, I’ve gotten a call from a clinician saying, “She’s taking her misoprostol [the pills that will expel the pregnancy from her uterus] today, is it possible for her to make her flight back to Texas tomorrow? She won’t make her follow-up appointment with us. Is that OK?” My answer is, of course, it’s OK. The saving grace is that abortion is so extraordinarily safe. She doesn’t have to have a follow-up appointment. This shouldn’t be a reason not to give her an abortion. But then the what-ifs start to tick off in your mind. What if she has an emergency? Well, she can go to the emergency room and just say she’s having a miscarriage. But what if more questions come up? It’s not really OK anymore to show up and say “I’m having a miscarriage” in a lot of emergency rooms. What is that doctor worried about? Is he trying to protect himself? Is he allowed to ask about travel? Is she allowed to not answer? But all these things start to tick off in my head and I realized how unprepared we are to be an asylum state. I feel unprepared as a physician to answer these legal questions. These questions are going to come up over and over. Whether you have a bottleneck or not, you’re going to be providing for patients who come in from out of state, and then how do we counsel them and how do we protect them and how do we protect our colleagues, even if we’re not worried about ourselves? That’s a tricky spot to be in.

TIMMARAJU: We’ve seen declines in doctors who are able to really do this work and we’ve seen declines in medical schools actively teaching this procedure, so criminalization of doctors is terrifying.

During their nomination hearings, some of the appointees who are now justices said they recognized Roe as settled precedent. How common is it for appointees to reverse course like that?

KOENIG: I don’t know empirically. But I have not heard of that being done frequently. I think there is a sense of outrage among many attorneys. We all try to have faith in our officials, whether they’re appointed or elected, and the coequal branches of government, that when you say you will do one thing, you will be true to your word. And I think this is a very concerning move, where you have people in the highest levels of office, who are basically saying, “No, I said one thing to get the appointment and now when I’m in the position, I’m doing something very different.”

What does this decision reveal about the changing nature of the court?

KOENIG: I think the part that gave me the most pause, or the most concern for the future, was the reference to histories that are sometimes hundreds of years old, to paint a picture of the world—at least the authoring justice side—as [Justice Alito] wants it to be. For a lot of people whose lives were not that great in the 1300s, and the 1600s, and the 1700s, to think that might be the vision and the future that a Supreme Court justice or Supreme Court justices might want to see returned to the United States… there’s something very chilling about that possibility. And if you’re saying that’s the blank slate from which we should be working, that suggests so many rights that anyone alive today has grown up with are all potentially vulnerable. Even when you think about concepts like freedom or equality, which are literally in the Constitution, how those get interpreted. And when you begin to ask, whose freedom? Whose equality? How do we even measure inequality in this country? I think we could see a very different profile of what is considered equal or nondiscriminatory than we did even 10 years ago.

“We’ve seen declines in doctors who are able to really do this work and we’ve seen declines in medical schools actively teaching this procedure, so criminalization of doctors is terrifying.”

mini timmaraju

Will we see a return to the pre-Roe back-alley abortions?

TIMMARAJU: There’s already an incredible network of organizations, on-the-ground abortion providers, and abortion funds in Texas right now, in Oklahoma, and other similarly affected states that are running networks to match people with care and providers, get them access to funds, and arrange travel. Pre-Roe, it was a different environment. Now you have a whole generation—50 years of people—who know how to access this care.

ANDREWS: We’ve come so far, and abortion pills in particular are a safe, effective way to self-manage an abortion. I just don’t think that we’re going to see the cliched coat hanger stuff. I do, however, worry about rural folks and folks who grew up in extremely religious contexts in particular. As someone who grew up in the rural South and who didn’t have sex education and didn’t know very much about my body until my early mid-twenties, it’s hard to imagine going from that to feeling OK self-managing an abortion, even if they do believe in abortion rights.

Where will you be focusing your work next?

KOENIG: I think that if we are going to limit options on abortion for a broad array of women across the United States, then we need to look at how else their health care can be maximized, and where else their health care may be vulnerable. Many reporting teams, like ours, have been looking at issues like what health care options remain available. Are there things bubbling up next that we should have on our radar that may limit access to reproductive care even further? And how do we begin to sound that alarm, if that alarm isn’t already ringing, so that people know where to look and where to fight? I would love to look more into the multigenerational aspect of this. So, for teenage children and older generations of women and men who really believe in access to reproductive rights, to health care, to birth control, can we bring them together in a united cause for the future that we want to see?

TIMMARAJU: We are a 360-degree advocacy electoral organization. We are really, really tracking all the bad bills in the states. There’s one moving in Pennsylvania right now. We are laser-focused on these elections.

HENNEBERG: It seems like, inevitably, what is going to change is that I will no longer get to live in the world that I lived in up till now, just letting other people deal with the law and the policy stuff while I’m just on the ground, providing abortions. I think those days are over, even in California, because if I want to support women and providers in other states, those things are going to have to intersect with each other. You hear about mobile vans parking on the border of some state, and someone needs to staff those vans. I had already thought that once my kids are older, I would get into traveling. That sounds just so rewarding. Physicians who are clinicians are thinking about these problems, like the questions we get asked by patients traveling from other states. [They] are going to need to learn the laws and integrate that into their medical advice. So, I’m excited to learn. I’m looking forward to learning that stuff so I can do a better job of serving those patients.

ANDREWS: I’m hoping to spend quite a bit of time on the ground here in the South, continuing to look at disparities about who is getting the health care they need and who isn’t. I’m interested in how we got to this point, where anti-abortion movements have gotten their funding, in looking at different anti-abortion legal societies, and that kind of thing. I’m also very interested in the ways that white feminism has influenced the abortion rights movement, and in a lot of ways it kind of screwed it up. I want to look at how the reproductive justice framework, which was coined by Black women in the ’90s, is a more holistic approach. I keep thinking about how this is all so bad, right? And in other ways, there’s this opportunity to finally build back better. That’s not to dismiss the very real human cost that comes with this. But when everything gets bulldozed to the ground, maybe we can start back with something that’s more inclusive and that actually helps more people in the long run.

Laura Smith is the executive editor of California magazine, co-host of The Edge podcast, and the author of The Art of Vanishing.

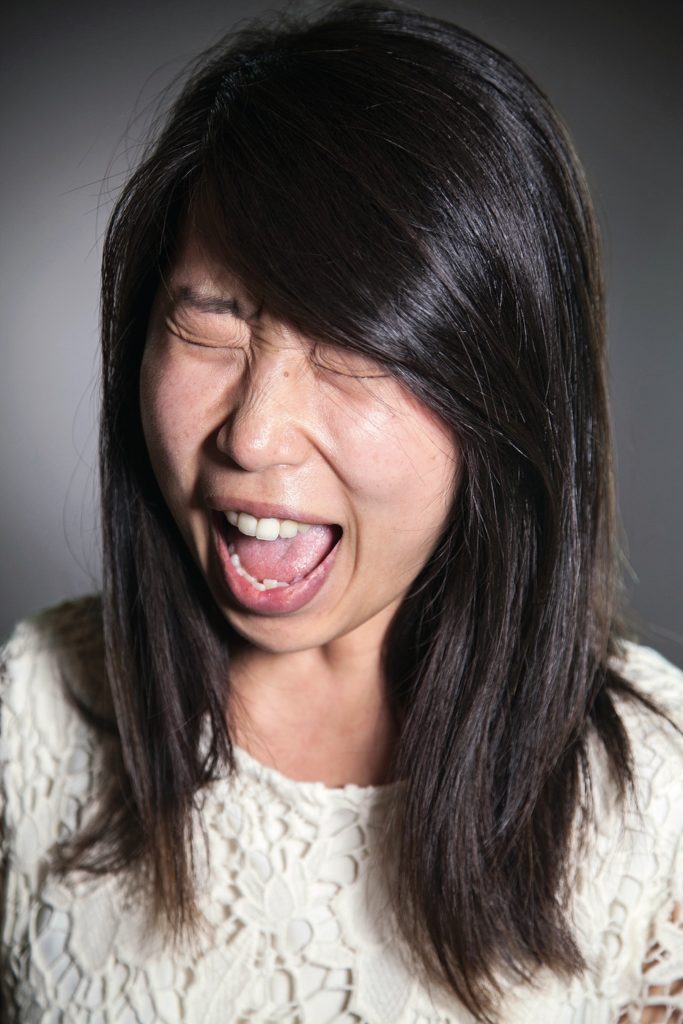

The images that accompany this article are from artist Whitney Bradshaw’s Outcry series of photographs, which have been on display at BAMPFA’s outdoor screen since shortly after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade on June 24. Bradshaw launched the project on the night of the 2018 Women’s March. It has since grown to include more than 400 photos of women expressing outrage and defiance against patriarchal oppression. Outcry will be shown at BAMPFA through November 8.

…

California magazine is an editorially independent non-profit magazine. We need your support to keep producing award-winning journalism about the world of Berkeley and Berkeley in the world. Please consider a donation in any amount. Fiat Lux and Go Bears!