To Phenocia Bauerle, the words “land-grant college” carry a particular weight. A member of the Apsáalooke tribe, she grew up in Montana, a state where, as she puts it, “it’s understood what a land-grant institution means: It means Native land was taken.”

But whenever she mentioned these implications to Berkeley higher-ups, stressing their responsibility as a land-grant institution to Indigenous communities, she recalls an unanticipated reaction: confusion. “Nobody got it,” she says. “Like, ‘I don’t know what that has to do with anything.’”

It was a moment of cultural whiplash for Bauerle. She earned her bachelor’s in 2002 from Montana State University, another land-grant school, attending tuition-free through the state’s American Indian Waiver program. Later, when she worked in Montana State’s Diversity Awareness Office, she could reference the school’s land-grant roots and the implication would resonate. But when she moved back to Berkeley in 2013 to direct the Native American Student Development office, she found that most non-Native Californians were ignorant of the history.

California’s tribes have been colonized three times over: first by Spain, then Mexico, and finally the United States. To date, around 55 California tribes have not been federally recognized. Of the more than 100 that are, many were only given recognition in the last few decades.

Bauerle sees these as factors in “the invisibilization of Natives and Native issues” in California. “In California, I think, folks don’t know.”

For a century and a half, land-grant universities have been telling themselves a story that goes like this: In 1862, amidst a brutal civil war, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Morrill Act, landmark legislation that granted Union states parcels of land to develop agricultural, mechanical, and military colleges. The hope, the act stated, was to “promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes.” Each state was allotted 30,000 acres of land per senator and representative. By selling or investing their land grants, states could create a fund which “shall remain forever undiminished.”

For most Americans, the moral of the Morrill story has been a self-congratulatory one about the democratization of higher education. However, recent data-driven research and reporting is forcing us to confront a darker reality.

California received nearly 150,000 acres, which it used to amass a hefty endowment for its future university system. Six years later, on March 23, 1868—Charter Day—Governor Henry Haight signed a bill that established the University of California.

For most Americans, the moral of the Morrill story has been a self-congratulatory one about the democratization of higher education. However, recent data-driven research and reporting is forcing us to confront a darker reality: America’s first public universities were financed by—and continue to benefit from—unceded Native land, seized through violence and broken treaties. Many schools still retain the surface or mineral rights to thousands of stolen acres.

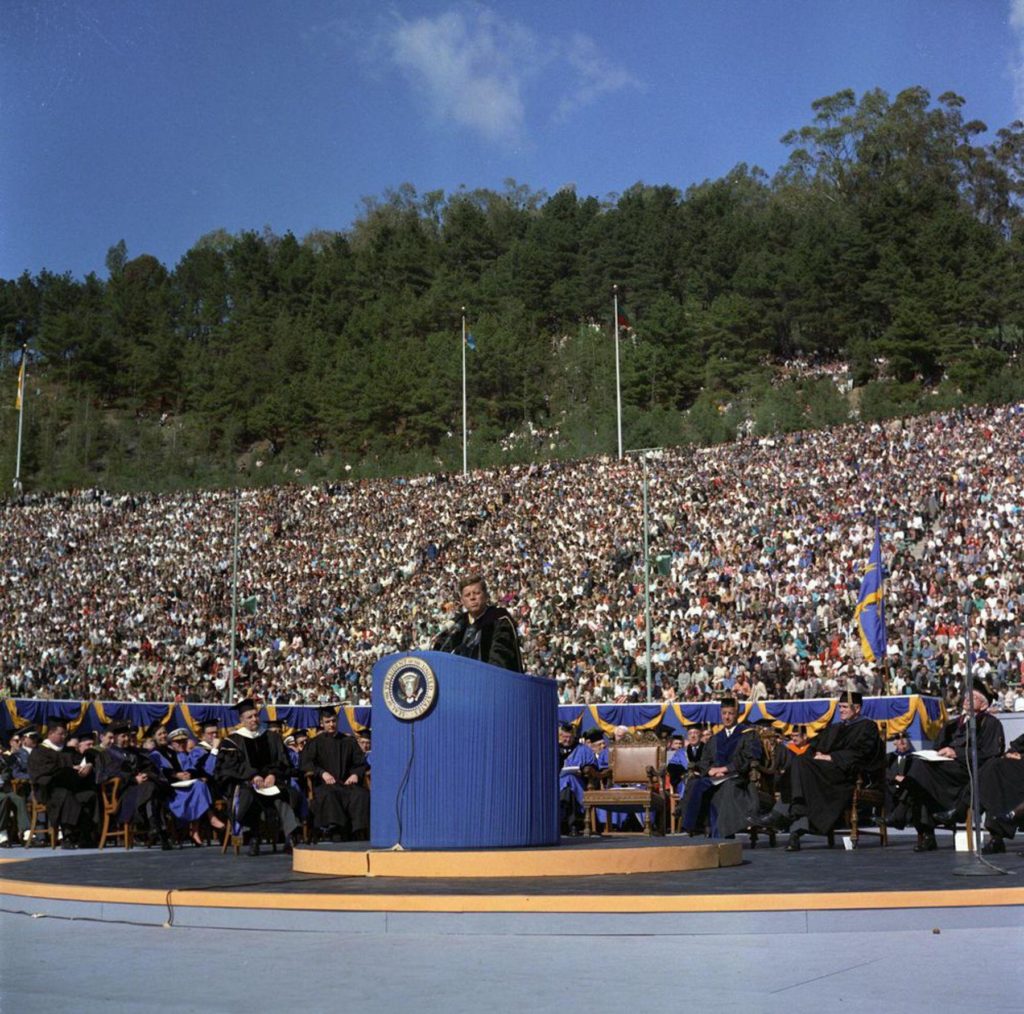

July 2, 2022, marks 160 years of the Morrill Act, the kind of round-numbered milestone the University of California might be expected to celebrate. For the centennial, President John F. Kennedy stood before a crowd of 88,000 at Memorial Stadium and proclaimed that “this university and so many other universities across our country owe their birth to the most extraordinary piece of legislation this country has ever adopted.” In 2012, a Lincoln impersonator in a stovepipe hat and flimsy beard commemorated the 150th anniversary at UC Davis by extolling the promise of Morrill’s land-grant legislation: that “each individual can start at the bottom of society and he or she has the right to rise.”

As the 160th anniversary approaches, many Indigenous people are wondering whether this might be the year the University of California and other land-grant universities begin to make things right.

What initially drew historian Robert Lee, Ph.D. ’17, to tell the story of the Morrill Act land grab was that, thanks to big data, it was finally possible.

Lee, who teaches American history at the University of Cambridge, began researching the subject at Berkeley in 2015. Holed up in a shared Dwinelle Hall office overlooking Ishi Court, he spent countless hours mapping thousands of nineteenth-century land deeds. For earlier generations of scholars, that kind of large-scale, data-driven historical project would have been nearly impossible; but with ever-improving geographic information systems (GIS) and vast troves of historical documentation accessible in online databases, researchers like Lee can now collate and track the expropriation of Indigenous land with relative ease.

Not that scholars have been champing at the bit to get at this information. “It’s not the case,” Lee emphasizes. “The way historians discussed the Morrill Act was through this frame of whether or not they were ‘democracy’s colleges’; to what extent the Morrill Act fulfilled its promise for democratizing education in the United States.” Over the years, land-grant colleges have been criticized for contributing to the very elitism they set out to counteract, and for underserving the Black land-grant colleges created by the second Morrill Act in 1890. (More than a century later, 29 Native American colleges, later amended to 35, would be designated as land-grant institutions under the Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act of 1994.) As for where the land originally came from? That was barely, if ever, addressed.

Perhaps that’s because the origins of America’s “public lands” were never truly a mystery. As Congressman Justin Morrill himself bluntly expressed it in an 1857 address, the land was “acquired by the displacement of the red man.” For Morrill, this acknowledgement was just a stepping-stone on the way to his primary concern: not letting the newly obtained land go to waste.

The 1840s were a decade of ravenous expansion for the United States. Emigrants and gold seekers were flocking west on the Oregon and California trails. Over the course of three years, the United States acquired Texas, the Pacific Northwest, and roughly 530,000 square miles of Mexican land. By 1850, it seemed poised to become the “extensive Republic” President Andrew Jackson had envisioned 20 years prior.

The most glaring hurdle was the same one the Pilgrims had encountered. The land was home to hundreds of Indigenous tribes and had been for millennia.

It was an obstacle overcome by force and duplicity.

In 1851, President Millard Fillmore dispatched three federal agents to compel California tribes to sign treaties relinquishing any claim to their ancestral homelands. In exchange, the federal agents promised, the tribes would be compensated and relocated to reservation land “forever set apart” for their families and future generations. Eighteen treaties were signed by 139 tribes. Yet when the tribes arrived at their new land, they were barred from entering. Instead, California’s Indigenous peoples were shuffled between ramshackle military reservations, which one Bureau of Indian Affairs agent later characterized as nothing more than “government alms-houses.” He wrote: “There is nothing in the system, as now practiced, looking to the permanent improvement of the Indian.”

In fact, none of the treaties was ever ratified. California’s lawmakers had balked at the idea of giving “the richest of our mineral lands” to the tribes. The signed treaties were disregarded by the federal government, leaving California’s tribes unrecognized, uncompensated, and unprotected.

With no federal treaties to shield them, Indigenous groups were at the mercy of the state. California’s governor dispatched militias to engage in what he described as a “war of extermination” against uncooperative tribes. In Humboldt, in Mendocino, in Yosemite Valley, and all across the state, thousands were systematically butchered. At the 1853 Yontocket massacre alone, more than 450 men, women, and children were slain in the middle of their annual harvest ceremony. By the turn of the century, an Indigenous population that exceeded 200,000 before the Gold Rush had been reduced to roughly 15,000.

“Wronging nobody, it will prove a blessing to the whole people now and for ages to come.”

Justin morrill

It was these kinds of freshly available lands that Representative Morrill approached Congress about in 1857. A steely-eyed abolitionist from Vermont, Morrill had no formal college education; but as a successful merchant and farmer, he’d grown exasperated by what he saw as the exhaustion of arable land. What good were new territories if current agricultural practices left that land depleted? What was required, Morrill argued, were colleges designed to encourage “useful knowledge among farmers and mechanics in order to enlarge our productive power.” His proposed legislation would utilize undeveloped land to help fund new agricultural and mechanical colleges.

President James Buchanan vetoed the bill in 1859 over states’ rights quibbles, but Morrill resubmitted the legislation two years later, amending it to include military training. “Wronging nobody, it will prove a blessing to the whole people now and for ages to come,” he proclaimed. The law passed easily. Lincoln signed the Morrill Act on July 2, 1862, right on the heels of the Homestead Act, which provided plots of land to those willing to trek west, and the Pacific Railway Act, which set aside millions of acres for the future transcontinental rail line. With those three pieces of legislation, Lincoln put the “arable land” of the West to use, definitively stripping it from the tribes.

Lee was not the first person to consider the land-grant colleges as part of what he terms “the settler-colonial theory”; his research was just the latest in an emerging body of work interrogating the foundations of American higher education. In 2013, MIT historian Craig Steven Wilder published the book Ebony and Ivy, which demonstrated how slave labor built the nation’s oldest universities, in some cases quite literally. Other scholars began applying this kind of scrutiny to land-grant schools. K. Wayne Yang, M.A. ’01, Ph.D. ’04, an ethnic studies professor and provost at UC San Diego, was one of the first. In his book, A Third University is Possible (published in 2017 under the pseudonym “la paperson”), Yang described how “land-grant universities are built not only on land but also from land.” Ultimately, Yang wrote, these schools are “intimately underwritten as a project of settler colonialism.” These concepts were expanded on by education researchers like Sharon Stein, assistant professor at the University of British Columbia, and Margaret Nash, professor at UC Riverside.

What was missing from this type of scholarship, Lee says, was the empirical component. “How did this actually work on the ground? Who got what land from who? How much did it raise?”

That was the work he began at Berkeley and continued during his postdoc at Harvard University. Relying mainly on data from the Bureau of Land Management’s corpus, he was able to map the bulk of Morrill Act lands, tracing what originally belonged to which tribes, what states eventually received the parcels, and how much those states made off the sale of the real estate. The picture that emerged was sobering.

In 1862, the majority of “public” land was in the West. As a result, Eastern, Southern, and some Midwestern states received vouchers, or “scrip,” to represent their share of Western acreage. Thirty-two land-grant colleges outside California, including Cornell, Purdue, and Clemson, received scrip for land within the state, which they used to raise millions.

At the University of California’s 50th jubilee in 1918, UC President Benjamin Wheeler cited the “endowment fund, derived first from the more than usually fortunate sale of public lands” as one of the primary reasons the university had survived and thrived.

California, on the other hand, had no need for scrip; it simply claimed land within its own expansive borders. But where other states immediately sold their land to speculators, the University of California effectively became its own real estate office, selling land plots in installments over decades.

In doing so, California generated capital and interest to help finance its university’s annual operating costs; in 1886, Morrill Act funds covered more than a third of expenses. At the University of California’s 50th jubilee in 1918, UC President Benjamin Wheeler cited the “endowment fund, derived first from the more than usually fortunate sale of public lands” as one of the primary reasons the university had survived and thrived.

By 1914, the University of California had sold everything but 1,402 acres. (In 2019, it still retained the mineral rights to about 442 acres.) That year, the Morrill Act endowment totaled $21 million, adjusted for current inflation—a sizable figure for a university that served only a few hundred students at the time.

In March 2018, Lee presented his preliminary findings at an Indigenous research seminar hosted by the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard. He gestured to a projected map of Morrill Act data, expressing his hope that this work could “update the methodology for drawing the frontier line,” and concluded with a plea for more collaboration.

Lee didn’t know it yet, but his soon-to-be reporting partner, Tristan Ahtone, a member of the Kiowa, was in the audience. One of Harvard’s 2018 Nieman Fellows, Ahtone was Indigenous affairs editor at the nonprofit magazine High Country News and had himself graduated from a tribal land-grant college in New Mexico. But he had little awareness of land-grant history or its ramifications until Lee’s lecture. “I was just generally blown away by the work he was doing,” Ahtone says.

After the presentation, Ahtone approached Lee and introduced himself. “Basically, I made a pitch to him, like ‘I’ve got a deal for you, if you want to do some journalism,’” he recalls. “He had the idea, and I had an idea on how to do something with it.”

So began a two-year investigative project. Ahtone, Lee, and their High Country News team created an open-source database mapping all of the Morrill Act information available: land parcels, tribal lands, money earned, tribes compensated or not. Their work culminated at the end of March 2020 with the publication of their cover story, “Land Grab Universities,” and the unveiling of the database. The team won the prestigious George Polk Award for their reporting, which the award committee noted “sent shockwaves through campuses across the country.”

Indeed. On April 20, Ohio State University professor Stephen M. Gavazzi, who had published a book celebrating the “bilateral bond” between land-grant schools and their communities in 2018, penned a chastened op-ed for Forbes entitled “The Original Sin Of Our Nation’s First Public Universities.” The High Country News story should “serve as grounds for swift acts of contrition from the leaders of every land-grant university,” Gavazzi wrote. In August, Hack the Gates, a project cosponsored by Colorado State University to study college admissions, argued there were only two legitimate responses: return the land, or give Indigenous students free tuition. A few months later, the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities released a statement acknowledging the inextricable link between Morrill Act schools and Indigenous dispossession.

Andy Lyons, Ph.D. ’12, and Rosalie Zdzienicka Fanshel, Ph.D. ’24, weren’t shocked by the revelations in the story. The surprise was that someone had so thoroughly beaten them to it. The two had been researching the origins of UC land grants, independently from one another, for months.

Back in 2019, Lyons, a program coordinator at UC Agriculture and Natural Resources’ GIS Statewide Program, had begun doing what Lee and Ahtone did but specifically for California, leading a team in overlaying Morrill Act parcels with Indigenous territories. Meanwhile, Zdzienicka Fanshel, a doctoral student in Berkeley’s environmental sciences department, had been researching how specific land purchases benefited the University of California’s founding—and founders. Then, “by the kind of research miracle one can only hope for,” the High Country News story dropped and provided her with all the data she needed. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is amazing!’”

She and Lyons immediately contacted Lee to talk shop, and a few days later, Zdzienicka Fanshel reached out to Bauerle about the possibility of hosting a forum on the “Land Grab” revelations. Bauerle, who’d already read the piece, was definitely interested.

In 2017, Bauerle had organized Berkeley’s first Tribal Forum, bringing together Indigenous scholars and representatives of more than 30 tribes for a discussion on how Berkeley could repair its relationship with California Indians. Since that event, Berkeley’s library has committed to being more culturally sensitive when digitizing and sharing Indigenous materials, and Berkeley has hired a full-time liaison to facilitate the return of ancestral remains and objects to tribal communities.

A forum on the Morrill Act “seemed like a next step,” Bauerle says. She sensed a chance to push for more, since the Berkeley administration leans “pretty heavily” on the findings from the Tribal Forum.

The UC Land Grab Forum was split up over two days, on September 25 and October 23, 2020. The first session contextualized the Morrill Act within California’s three centuries of colonization and included a talk by Beth Rose Middleton Manning, Ph.D. ’08, UC Davis’s Yocha Dehe Endowed Chair in California Indian Studies, who envisioned some opportunities for the University of California to move forward. There was considerable precedent, she explained, for both land returns and tuition waivers for Indigenous students. Other options included establishing UC satellite campuses on reservations and comanaging land alongside tribes.

The second session highlighted existing initiatives between tribal communities and the University of California and suggested new ones. “What we ask the people of today is to help us restore our culture, restore our spirituality, restore our rights to the land,” exhorted Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Central Coast’s Amah Mutsun Tribal Band.

More than 1,000 people took part. Attendees included David Ackerly, dean of Berkeley’s Natural Resources College, staff from the office of UC President Michael V. Drake, and Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ. In an email statement to High Country News that December, Chancellor Christ wrote, emphatically, “Now more than ever, we, as a university, must take immediate action to acknowledge past wrongs, build trusting and respectful relationships, and accelerate change and justice for our Native Nations and Tribal communities.”

Since the High Country News story was published, there has been a broad range of responses from the 52 land-grant institutions. From the University of Florida to MIT, campus newspapers published write-ups, student governments petitioned for internal investigations, and advocates called for increased recruitment of Indigenous students and faculty. Many schools hosted their own forums or wrote land acknowledgments to recognize Indigenous land dispossession. Some colleges, like the University of Connecticut, used the High Country News data to do even deeper dives into their own Morrill Act foundations. When the University of Minnesota received a $5 million grant in early 2021, it vowed to use the funds to address racial justice, including meeting the requests of Minnesota tribes, which included housing and scholarships for Indigenous language students and developing a digital Dakota language storytelling archive.

In terms of decisive response, though, the gold standard at the moment is Ohio State University. Its situation is unique: It’s a land-grant institution located in a state with no federally recognized tribes—a direct result of treaties that methodically relocated the state’s original inhabitants. In an attempt to reckon with this history, Ohio State created and funded the Stepping Out and Stepping Up project, developed in partnership with the First Nations Development Institute, an Indigenous economic support organization. Headed by Gavazzi, the author of the penitent Forbes op-ed, the project team began by interviewing tribal leaders whose homelands financed Ohio State in order to discuss how best to make amends. The responses from the first 12 interviewees were briefly described in an article for the American Association of University Professors; while some merely wanted apologies, others sought “tangible reparative activities,” such as scholarships or returned land. In all discussions, there was “a palpable sense that universities must have an ongoing commitment to restitution and healing.”

Ahtone and others point to Ohio State’s response as exemplary, but also exceptional. “Ohio State is one of the only institutions that has buy-in from the administration,” Ahtone says. Everywhere else? “For the most part, it’s small groups of people who are trying to do what they think is the right thing.”

In late April though, as this story was being reported, the UC Office of the President made a consequential announcement: Beginning in the fall of 2022, the University of California will provide full-tuition scholarships for California residents who are members of any federally recognized tribes. The new program, called the UC Native American Opportunity Plan, will cover the cost of in-state tuition and student service fees for Native American and Alaska Native students attending any of the UC system’s ten campuses. As for California’s nonfederally recognized tribes, the office said there could be separate scholarship opportunities available through external organizations, which it will provide information about in the future.

In late April, as this story was being reported, the UC Office of the President announced that, beginning in the Fall of 2022, the university will provide full-tuition scholarships for members of federally recognized tribes residing in California.

“The University of California is committed to recognizing and acknowledging historical wrongs endured by Native Americans,” UC President Drake wrote in a letter to the chancellors, expressing his hope that this move will “continue to position the University of California as the institution of choice for Native American students.”

“This is really exciting,” says Stanley Rodriguez, a councilmember of the Santa Ysabel Band, reacting to the news. Rodriguez also sits on the UC President’s Native American Advisory Council, alongside Lopez, Bauerle, and other Indigenous scholars, faculty, and tribal leaders. He said the scholarship was already on the council’s agenda when he joined last year. “Traditionally, the UC system, the cost had been prohibitive for many people, especially from non-gaming tribes,” he notes. “So this is an incredible step at removing those obstacles.”

As exciting as the scholarship news is, Rodriguez added, “I need to qualify that this is not the end. But it’s a step.”

Rodriguez is part of the Kumeyaay Nation, the original residents of coastal land running from San Diego County into Baja California. In 1852, Kumeyaay representatives signed the Treaty of Santa Ysabel, one of the 18 treaties eventually rejected and buried by the U.S. Congress. As the Kumeyaay were pushed east, their unceded homelands were doled out to land-grant universities, including the University of California. The Kumeyaay were never compensated.

“It’s a living piece of legislation. These endowments are still generating funds and they’re generating multiplier effects.”

Robert lee

“As far as financial restitution, I mean, in the end, we were pushed off the coast, into the mountains,” Rodriguez continues. “I would like to see at least a portion of that land [returned], so that we can continue with our ocean culture and everything that comes with it—harvesting rights, fishing rights, gathering rights.”

That could be a long way off, however. When asked for comment, the UC Office of the President said there were no current plans for either land returns or financial restitution, while adding that they continue to “seek the advice” of the Native American Advisory Council.

The thing the university mustn’t do, Lee says of his alma mater, is pretend the Morrill Act is distant history. “The endowments are still there…. It’s a living piece of legislation. These endowments are still generating funds and they’re generating multiplier effects. And they have been over time.”

“This is corporate personhood,” he says. “The university from the 1860s is the university today.”

Hayden Royster is a Bay Area writer who covers religion, politics, and culture.