Let’s start at the end.

In early 1990, Joan Brown began working on a 13-foot obelisk in her studio in San Francisco. It was a shift from the figurative portraits that had made her famous. Around the same time she began teaching in Berkeley’s Department of Art Practice in 1974, she had become increasingly interested in Eastern religions, transitioning away from work for museums and collectors and moving toward public art. Before, her work had focused on her family, her own body, and household objects. Now, she was in the realm of the ethereal, creating a vision that came to her while meditating, foretelling of a golden age when all beings would live in harmony.

This obelisk was intended for the Eternal Heritage Museum, near Puttaparthi, in South India, to honor her beloved yogic guru’s birthday. It had a turquoise background with different animals at the bottom—mouse, snake, lion, lamb, eagle, and peacock—and each of its five sides was adorned with the Sanskrit and English words for truth, righteousness, nonviolence, peace, and love. A luminous golden orb, meant to represent the universality of her guru’s teachings, perched at its point.

Brown arrived in Bangalore with her adult son and some assistants to begin installing the obelisk in the museum. She sent ecstatic letters to her husband about the installation’s progress and a moving meeting she and her son had with the guru. In her last phone call home, she asked her husband to look out for her son, who would be returning to the United States while she remained in India to oversee the finishing touches to the installation. Not long after that call, a concrete turret in the Eternal Heritage Museum collapsed on her, killing her instantly, along with two assistants, and destroying the obelisk.

What happened next has been the animating concern of religion for centuries. Mike Hebel, Brown’s husband, told me that he and Brown believed in reincarnation. But there is also the question of the afterlife of the artist’s work. Would her creations mean anything to people in the future? As the artist Squeak Carnwath, Brown’s colleague in the Department of Art Practice, said, “I feel that we’re all creating and recording history. And it may not be the history of world wars—or it might be. But it’s really an important history. It’s visual culture. And it’s different from stuff that’s written in books.” Most artists, even those who were famous while alive, fade into oblivion. Carnwath said that the work of some of Brown’s contemporaries are currently “languishing in a basement somewhere.” For the time being, Brown has been spared that fate. Now, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is exhibiting a large retrospective of her career. Cocurator Nancy Lim ’04 said that she hoped the retrospective would reignite scholarship in Brown’s work. “There is so much more to explore.”

“You’re getting a message even though you don’t know what the message is,” Carnwath said. “And that’s what Joan was doing. Making a record of her time on the planet.” Her time on the planet proved remarkable, but the golden age of harmony she predicted feels far off these days. So what was she trying to tell us?

Joan Brown was raised in the Marina District of San Francisco by a banker father who drank too much and a mother who was epileptic and often threatened suicide, though she waited to follow through on that threat until Brown was in her thirties. She went to Catholic school, which she hated. Art was not in the curriculum. Then, by chance, after high school, she came across an advertisement for the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), the oldest art school in the West, whose staff included renowned artists like Clyfford Still, Richard Diebenkorn, and Elmer Bischoff ’38, M.A. ’39, the latter who would become a great mentor to Brown. She swung by in 1955, and found her life’s work.

Though initially she was plagued by self doubt and considered dropping out, by 1956, she was working with Bischoff. He counseled her to follow her intuition, advice that would guide her for the rest of her life, and encouraged her to draw and paint what she saw around her: a Thanksgiving turkey, her mother, and increasingly, herself. Like other Bay Area figurative painters, she was melding abstract expressionistic brush style with more realistic portraiture. As art historians Karen Tsujimoto and Jacquelynn Baas wrote in The Art of Joan Brown, “Brown claimed herself as primary subject matter for her art … much of Brown’s oeuvre can be seen as a visual diary of her life and a product of her penetrating self-scrutiny.”

Success came quickly. By the time she was 19, she was exhibiting her work in the Six Gallery, which Tsujimoto and Baas characterized as “one of San Francisco’s early and important artists’ cooperative galleries.” Not long after she graduated from the institute, collectors began buying her work. When she sold one of her first paintings, she brought the check to her father, who was the branch manager at the Bank of America on Market Street. He looked at her and looked at the check. “It was a pretty nice amount,” Brown’s husband Mike Hebel recalled. “He authenticated the check before he deposited it because he was just really shocked.”

Around the same time, the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired one of her paintings, and in 1960, her work was exhibited alongside Helen Frankenthaler and Georgia O’Keeffe. The Whitney included her art in one of its traveling exhibitions, and she was featured in a Look magazine article.

She began teaching in 1959, first at a private high school in San Francisco, then moving between various colleges in Northern California until she finally landed at Berkeley in the Department of Art Practice in 1974, where she would remain until her death. Carnwath, who Brown first brought to Berkeley in 1982, said that students were drawn to Brown. Hebel said she was sympathetic but didn’t shy away from honest feedback. Like her mentor before her, she was known to tell her students, “Do what feels right to you.”

“She loved teaching,” said Hebel. “Joan felt that anyone could be an artist, that it was not a select few who were destined.” She got to put this ideology into practice one year when a woman in her sixties applied to the program at Berkeley. Brown’s colleagues felt the applicant was too old. “How much time would she have left to be an artist?” Hebel recalls Brown’s colleagues telling her. “Are we wasting our time that we could be putting into a 30-year-old or 25-year-old?” But Brown was insistent that she saw promise in her work and the woman was eventually accepted.

While Elmer Bischoff had counseled Brown to paint the things she saw around her, it posed an enormous risk to her standing as a serious artist. The things around her were “domestic things”; pets, her son and husbands, the stuff around her house. She might easily have been dismissed as quaint, a nice woman painter. Her insistence that these things were worthy of large canvases and artistic inquiry was quietly revolutionary. “It’s a kind of radical thing to do it with love instead of fetishizing it, and I think that’s very powerful,” said Carnwath.

“She was one of the most unselfconscious artists whose work I’ve ever really studied,” said Janet Bishop, the head curator of SFMOMA. “One of the things that we’ve gotten a huge kick out of is her love of holidays.” If painting holiday scenes was uncool, Brown didn’t care—or rather, she made it cool. “She’s never sentimental about the holidays,” added Nancy Lim, the cocurator of the Brown retrospective, “but there is an earnestness. So how does she strike that balance? It’s amazing.”

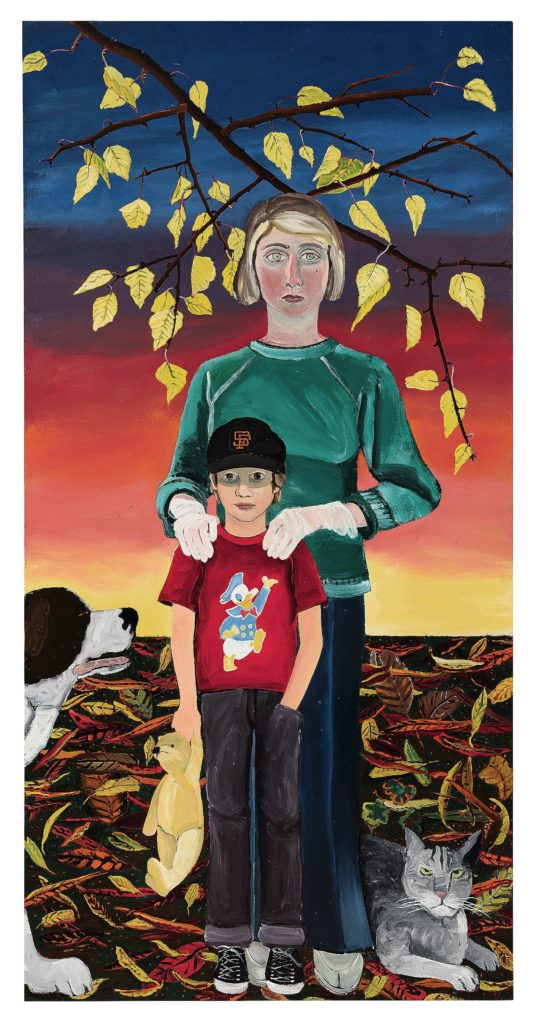

In one such painting, Christmas Time 1970 (Joan + Noel), Brown poses casually with her son and the family cat and dog. It’s California, so of course, there are no overt signs of winter; the only hint of Christmas is the title. With Noel’s stance and casual expression, the way his stuffed bear dangles from his hand, Brown captures something ineffable and tender about the ordinary moments of boyhood and family life.

Over the course of her life, Brown had many incarnations, once saying, “I’m not any one thing: I’m not just a teacher, I’m not just a mother, I’m not just a painter, I’m all of these things, plus.” She was married four times. Unlike many famous artists, she was, by all accounts, a devoted parent. Her son, Noel Neri, told an interviewer, almost sounding surprised, “She really was a good mother.” She didn’t just put him in her compositions, she also included him in her process. “She loved for me to talk to her while she was painting,” Neri said.

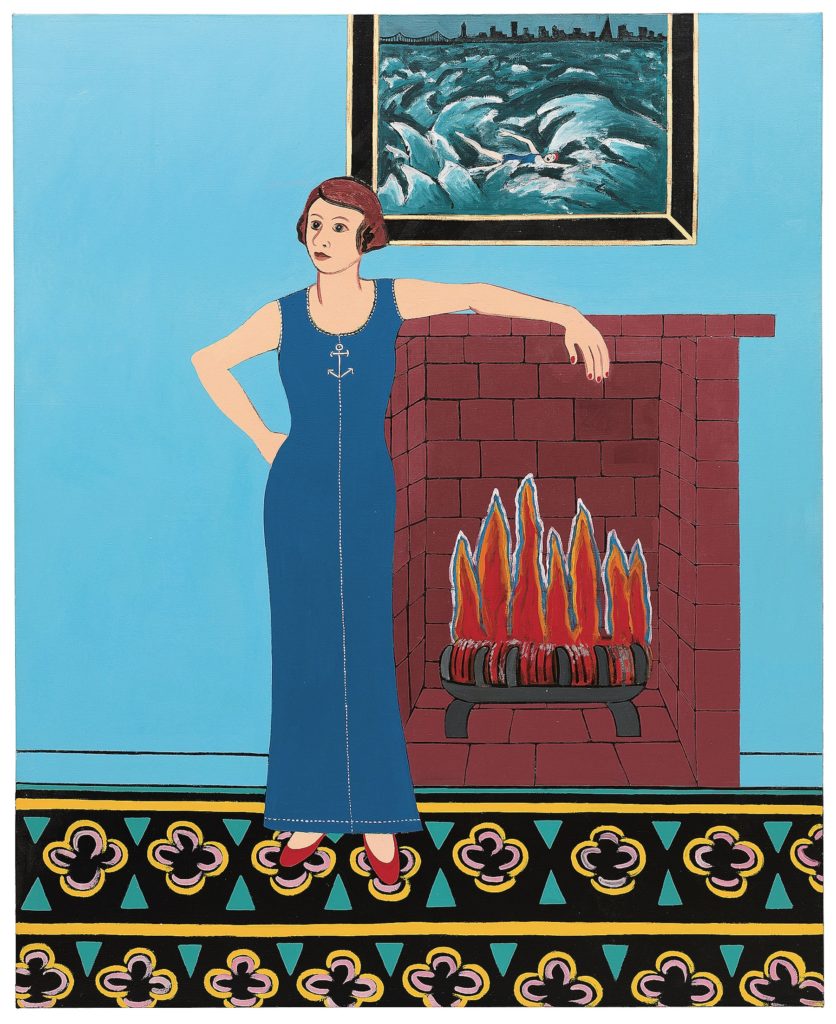

She was a committed, albeit not entirely talented, swimmer. She trained with Charlie Sava, a locally celebrated swim coach, and did a number of open water swims. She was one of six women to sue the Dolphin Club, the storied San Francisco swim club where members swim the frigid bay sans wetsuits, to force it to go co-ed. She populated her paintings with people from all corners of her life: the husbands, her son, pets, mentors, her swimming coach.

But perhaps most striking are her self-portraits. She seemed to understand something about her own eyes, which, clear green and almond shaped, were her most salient feature. Though she paints them simply, she somehow always gets them exactly right.

Some of her most remarkable self-portraits are the ones she painted about her Alcatraz swims. During one, she nearly died when a freighter came too close to the swimmers. The resulting portrait, After the Alcatraz Swim #3, shows a woman sitting serenely at a desk in a lushly carpeted room, a painting of turbulent water and flailing swimmers behind her. The vibrancy, the turmoil, the collection of After the Alcatraz Swim paintings; taken as a whole, it leaves the impression of a woman who was leading an experience-driven life. Brown had told Hebel that she had an intuition that her life would be short. In her work, there is the sense that she was trying to cram everyone and everything in.

Brown had always been ambivalent about the art world. Hebel recalled that dealers in New York couldn’t get enough of her thickly layered figurative work and urged her to make more, which she did for a while. When it no longer felt authentic, she moved on. “She did what she wanted, not what the market wanted,” Hebel said.

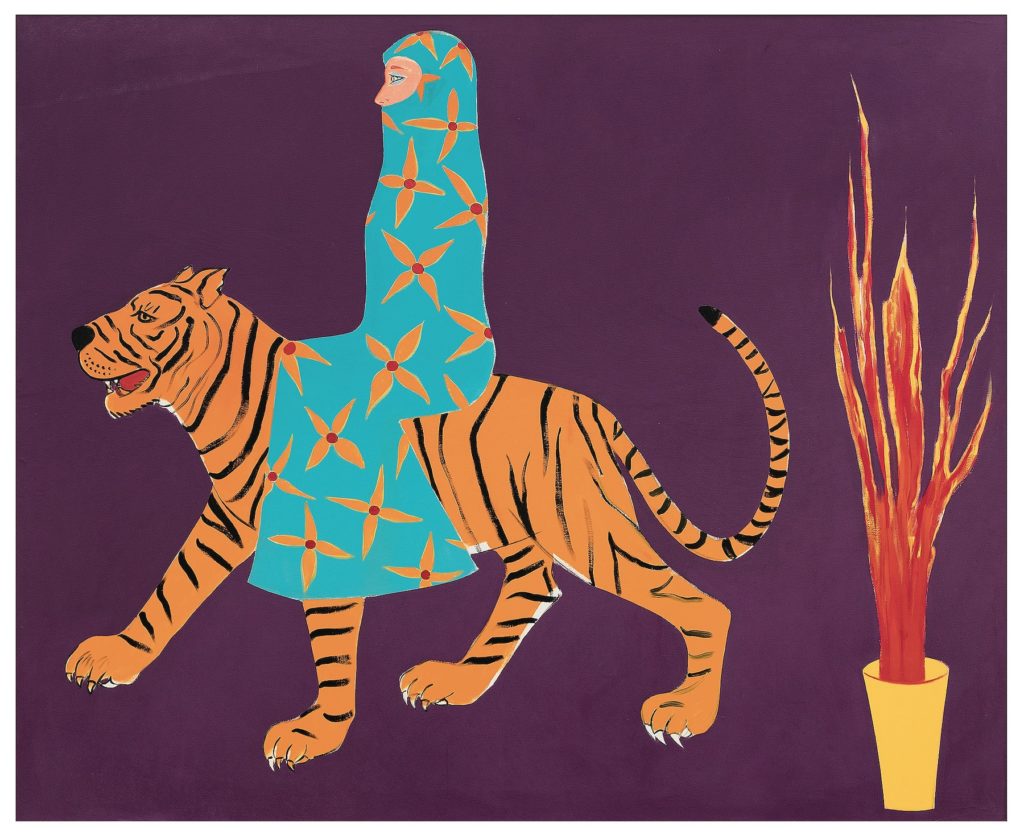

One of her most important, least studied incarnations was her last. Again, it involved an enormous risk. In the ’70s and ’80s, Brown began traveling to Egypt, Mexico, and Japan, and was reading about mysticism and ancient cultures. Ancient symbology began making its way into her work. In 1979, she met her fourth husband, Mike Hebel, a cop turned lawyer, at the Ananda Community House in San Francisco, a spiritual organization focused on yoga, meditation, and other spiritual practices, where they both were members. When Hebel met Brown, he had no idea that she was a renowned artist, which he argued was for the better. “I would have been intimidated,” he said. He was already feeling that way because she was six years older than he was. Early in their courtship, she invited Hebel to one of her shows. He was nervous and asked if he should study to prepare. She laughed. “Many people aren’t going to know more than you do. And probably many will know less.”

Hebel and Brown were married in a Hindu ceremony at SFMOMA in 1980. After that, nearly all of Brown’s work was spiritual in nature. The pair did a Himalayan pilgrimage for their honeymoon, and it was during this trip that they sought out one of India’s best-known (and controversial) yogic gurus, Sathya Sai Baba. They went to his ashram for a blessing ceremony. Sai Baba, who died in 2011, was regarded as a deity by his followers and accused of being a child-molesting fraud by critics. He cut a remarkable figure with his trademark orange robes and Jimi Hendrix hairstyle. As he walked down the aisle between his followers, he and Brown made eye contact. Tsujimoto and Baas wrote that, at that moment, she “developed a red, third eye on her forehead.” Hebel said, “Something opened for her. Whether it was the third eye, I don’t know. But there were definite physical, observable manifestations of the effect of that encounter. And from that encounter onward, she was a devotee of Sathya Sai Baba.”

From a distance, Joan Brown’s career appears chaotic. At different times, she drew inspiration from Mesoamerican culture, Matisse, and Rembrandt. She painted dogs and children, but also the dawning of a new age. For all that, Squeak Carnwath sees a throughline in her works. “I see them as really connected in the color palette, in the ambition, the size. Her quest for some kind of spiritual grounding is in all the work. It’s just that it got more direct, maybe.”

The critics weren’t always kind and many were dismissive of her spiritual turn, one calling it “a fallow period.” But Brown didn’t care. Hebel said that at this phase in her life she got the affirmation she needed from her students. Her initial skepticism of critics, collectors, and investors was now in full bloom. In 1983, she penned a letter to an art magazine. “If the art historians and critics would abandon their rational, linear thinking and make an attempt to connect to their feelings and intuitions, they may discover a clue to the real meaning behind a work of art,” she wrote. Her lens had widened. She was no longer making a record of her life. Now she seemed to be preparing for the next.

At about eight o’clock one morning in 1990, Mike Hebel got a phone call from Michael Goldstein, the American head of the Sri Sathya Sai Organization. Joan was finalizing the obelisk for her guru Sai Baba’s Eternal Heritage Museum. “Are you sitting down?” Goldstein asked before telling Hebel that Brown was dead. Hebel doesn’t recall much of the conversation, but he told Goldstein, “Joan’s where she wanted to be. Do the cremation there.” He had a court case at 8:30. He went and attended to three or four more of his cases, then came home and called Goldstein back. “Did you just tell me a little while ago that Joan was killed?”

More than 30 years later, the news has settled in. “That’s where her ashes would have gone anyhow,” he said. “That’s where I want my ashes to be. So she just got there earlier than she thought—earlier than I expected.” She was 52 years old.

There was a memorial service at the San Francisco Art Institute. Joni Beemsterboer, a friend from the Dolphin Club, recalls that at the memorial, many artists spoke. Near the end, a tiny woman approached the stage from the back of the room. She began, “I know you all painted with Joan Brown. I painted Joan Brown. Every Friday, I did her toes and nails.”

There was a retrospective held jointly by the UC Berkeley Art Museum and the Oakland Museum of California eight years after her death and then largely silence. This fall, SFMOMA announced the first major retrospective of her work in more than 20 years. The art has been collected from every stage of her life, from young womanhood and motherhood to the ethereal concerns of spirituality. “She was thought of primarily as a second-generation Bay Area figurative artist,” said Janet Bishop of SFMOMA. “Over the course of working on this exhibition, I came to appreciate how she really comes into her own after that, and that her most distinctive contributions are later on in her career.”

Returning to Carnwath’s idea that every artwork is a message, it’s tempting to try to read the show for direct meaning. Perhaps Brown is urging us to remember that we are many-sided beings who, if we are lucky, will experience many phases over the course of our lives, that we should follow the irrepressible parts of ourselves, even if the money makers and the critics don’t like it. Or, maybe there is a message to be gleaned by following the course of her career, which, at the end, took a more universal view. But perhaps we are grappling in the wrong medium. It is, after all, a visual message.

Laura Smith is the executive editor of California and co-host of The Edge podcast.