A Cal Discoveries tour to Egypt missed some historical sights, but witnessed history in the making.

On January 26 of this year, a Wednesday, Bob and Charlotte Sproul arrived in Cairo along with 33 other travelers on a CAA Cal Discoveries trip to Egypt. Some unrest on the streets delayed the bus from the airport, but the largely peaceful protests of the day before seemed to have largely subsided, and the tour group made it to the InterContinental Cairo Semiramis without much difficulty.

That night around 11, the Sprouls went for a drink in the lobby bar. Outside, a panorama of classical Egypt shimmered in the still evening: city lights on the Nile, obelisks and lion statues on the Kasr Al-Nile bridge.

Bob Sproul ’69, who is the assistant dean of development at Boalt Hall, saw someone run past. “Look,” he said, “they’re jogging. It’s cool out now.”

Charlotte ’71, M.A. ’74, who was serving as the Cal Discoveries trip manager, paused. Several more people ran by. “I don’t think they’re jogging,” she said. “I think they’re being chased.”

In a matter of seconds, police boats appeared on the Nile, shooting water cannons and lobbing tear gas that wafted into the bar. The Sprouls’ eyes started to burn. Hotel employees quickly arrived with handkerchiefs.

“That was the first little clue that, hmm, this could be really interesting,” Charlotte says.

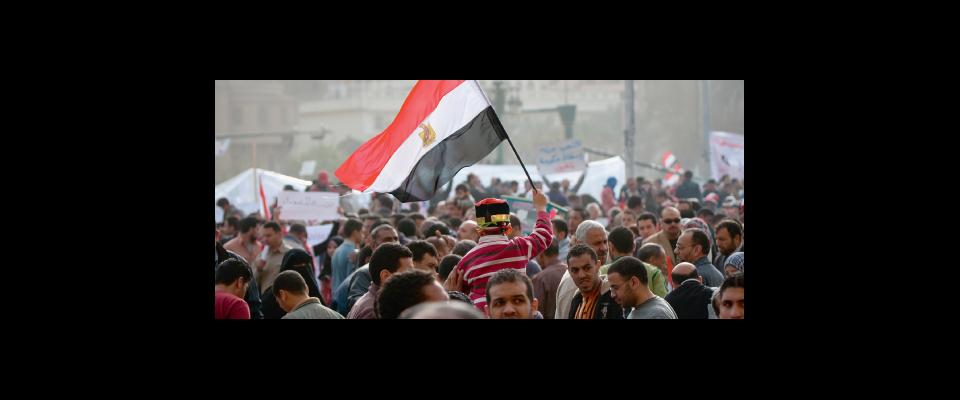

On the streets around them, the historic Egyptian uprising was just flaring up. The Sprouls, along with their fellow Cal Discoveries travelers, had landed right in the middle of it. Over the next 48 hours, from their hotel on Tahrir Square, they would witness some of the largest and most significant protests of the Arab Spring. Within a month, the president of Egypt would leave office, the protests would spread across much of the Middle East, and Bob Sproul would, in a small way, become part of the story. The tour was cut short; the travelers didn’t get to see the Nile or Luxor, but no one complained about exchanging ancient history for current events.

“I don’t think anyone felt they were shortchanged on this trip,” Bob Sproul says. “At all.”

George Saywell ’60, MBA ’63, and his wife, Nancy, had never been to Egypt before. “Every one of our friends who had been on the Nile trip said, ‘This is the trip of a lifetime, you’ve got to do it,'” he says now.

They arrived in Cairo a few days before the rest of the group. The Saywells did typical Egyptian tourist stuff: They went to the Khan Al-Khalili marketplace. They toured the museum. They got trapped in a rug store by an aggressive salesman. Saywell pulls out a photo album and shows pictures of him and his wife smiling in front of the pyramids, the Sphinx, a camel, a steady color palette of desert sand and blue sky.

He flips the page and the entire trip changes instantly: Here are protesters on the Kasr Al-Nile Bridge. Here are tens of thousands of people pushing forward against a line of police in riot gear, with the white trails of tear gas and the darker smoke of fires rising to the sky.

“That’s the time the hotel management said, ‘Vacate the lobby,'” Saywell says, pointing to one of the protest photos.

Just hours earlier, Saywell had gone to the hotel concierge desk to ask about the agitation outside. “The concierge said, ‘Oh, people are just upset with high prices and inflation,'” Saywell says.

This was true. But if the concierge and the travelers didn’t yet understand the significance of what was happening outside, they weren’t alone.

John Fossum ’63, J.D. ’66, and his wife, Janet, had also arrived in the Middle East a few days early. When the first protests, on Tuesday, January 25, were reported on television, Fossum called the hotel and the travel agency to make sure the trip was still on. “Both said, ‘Yeah, yeah, everything’s OK,'” Fossum says.

Although there were tens of thousands of protesters on Wednesday, it seemed at the time like the situation might cool down. Even after the Egyptian army replaced the police late Friday, the outcome wasn’t clear.

“You got the impression, once the police were sent home, that it was peaceful,” Saywell says. “It was just going to be a massive protest.”

On Thursday, January 27, the Egyptian government cut off the Internet, blocking social networking sites that had helped protesters to coordinate plans. The day was fairly quiet, and the Cal Discoveries travelers toured the Egyptian museum and returned to the hotel for dinner. With the Internet accessible but still spotty, Saywell couldn’t send emails, so he called his son in Texas and left a message saying, “We’re all OK.”

Charlotte Sproul managed to send a short email back to the Cal Discoveries office to say, “Everything’s going well. Perfect group to be in Egypt.” Somewhat presciently she added, “They’re going to come back with some amazing stories to tell.”

“At the time,” she says, “I figured, ‘Oh, well, we’ll get out of here and go on to Luxor. The protests probably aren’t there yet.'”

The Cal Discoveries tour guides planned a normal day for Friday. In the morning, the travelers left to see the Giza pyramids and the Sphinx. They returned to the hotel at noon for lunch. The protests were expected to start up again in the afternoon, as demonstrators called for a “day of rage.” The tour operators recommended the travelers remain in the hotel until they could get a better idea of what was happening.

From their 14th-floor balcony, Charlotte and Bob watched the protests escalate. Tens of thousands of protesters jammed the bridge, pushing against the police. Tear gas rocketed through the crowd.

Downstairs in the darkened lobby of the InterContinental, journalists began to arrive. Charles Levinson of The Wall Street Journal was staying in the hotel and heard about the Cal Discoveries trip. He thought there might be a story in the Cal grads who had been in school for the protests of the 1960s seeing student protests in Egypt. He asked for the biggest radical among the travelers. They gave him Bob Sproul.

Friday afternoon, as the protests intensified, Sproul, Levinson, and three other travelers decided to see the bridge up close. They still didn’t know how big the protests would get. “Even the Wall Street Journal reporter was thinking, ‘student revolt here, student revolt in Berkeley,'” Sproul says.

But just outside the doors of the hotel, it became apparent that this was more than a student protest. Sproul was on the Kasr Al-Nile bridge taking pictures when a man came running toward him, yelling in Arabic. Sproul decided to retreat back to the hotel and brought with him three new acquaintances: two Italian journalists and an Egyptologist, all of whom he’d met on the street.

They went out on the balcony of their hotel room to watch protesters battle riot police. Charlotte stood in front so that no one would see the Italian journalists filming the scene. A few minutes later, the reporters asked to use the room phone.

“Sure,” Charlotte said. “These calls are to where?”

“To Rome,” the journalists said.

“So they paid me for the phone calls to Rome,” she says.

Just after 6 p.m., the hotel went into temporary lockdown. Guests were asked to stay in their rooms. Outside, things were getting increasingly contentious. There were gunshots. After a few hours, the hotel reopened everything except the first floor. Charlotte and Bob Sproul went to the second-floor Thai restaurant.

“We watched a car get swarmed by 100 protestors and just disappear,” Bob says. “I think the person in that car was killed in front of us. Then we went down and had dinner in this Thai restaurant.”

Both Sprouls agreed on the word: surreal.

By the morning of Saturday, January 29, it was clear that the protests would not blow over, and that the trip could not continue. Overnight, explosions shook the InterContinental—Bob Sproul says it was the gas tanks of police vehicles being set on fire. The overwhelmed police had left the city and the army had moved in, and clashes between protesters and Mubarak supporters had intensified. Hundreds of thousands of people still jammed Tahrir Square, now watched by tanks.

John Fossum walked out in the morning to survey the scene and was surprised at the lack of belligerence of the interaction between army and protesters.

“People were climbing on the tanks, dancing on the tanks,” Fossum says. “It was almost a jubilant sort of thing.”

The local tour operator planned to move the entire Cal Discoveries group away from Tahrir Square to Cairo’s other InterContinental, a hotel closer to the airport and removed at least from the center of the action. It was a much more nerve-wracking trip than the ride from the airport, past the tanks on the streets and the remains of burned-out police stations, but it was largely uneventful.

The entire group made it, except for Bob Sproul, who at the last minute, decided to stay behind. “I said, ‘I’ll be damned if I’m going to go sit out in a mall for two days,'” he says now.

“I was asking, ‘You have money? You have your passport?'” Charlotte Sproul says. “I honestly thought I wouldn’t see him for a few days.”

She paused for a second, before adding, “Oh well. He’s a big boy.”

Bob Sproul is literally as well as figuratively a big boy. In the Wall Street Journal article, he is pictured in a navy-blue shirt, his silver hair emerging from under a Cal baseball hat, standing in front of a tank. He is in absolutely no way inconspicuous amid a 100,000-person protest in a major Middle Eastern city, so it isn’t surprising that he appears to have made a number of acquaintances on the way to the square.

Levinson reported in The Wall Street Journal an exchange between Sproul and one young protester, who ran up holding a tear gas canister made in the United States, saying, “This is the freedom you bring.”

Sproul responded quickly, “The American people are different than the American government.”

“It took me 20 minutes to stop my heart from jackhammering,” Sproul says now. “But Charles kept looking at me, going, ‘These people don’t have a beef with you. They may have some problems with our government, but they have a beef with their own government, and they’re actually happy you’re here because they want to get the story out.'”

Even that Saturday, Sproul says, “It really felt like students without weapons, very nonviolently going about their business, bringing to the world’s attention the injustices there.” Ten days later, as he sat in his Berkeley office and reflected, the danger was far more apparent.

On February 2, Mubarak supporters attacked protesters in one of the most violent days of the uprising. Mubarak resigned on February 11, three weeks after the start of the protests. In March, Egyptian voters approved constitutional amendments including election reform. In April Mubarak and his sons were arrested for corruption and murder, along with other high-ranking members of his regime. By August, their trials had begun. Protests have continued in Tahrir Square, however, as demonstrators demand constitutional reforms. Parliamentary elections are scheduled to take place in November, with presidential elections early next year.

Much to Charlotte Sproul’s surprise, Bob, still accompanied by the reporter, made it to the group’s hotel that same day. The next morning, at 7:01—one minute after a 6 p.m.–7 a.m. curfew imposed by the Egyptian military government—the travelers boarded a bus for the airport.

The airport was a scene of chaos as stranded travelers and Egyptians struggled to get out of the country. The flight board spun like a slot machine as flights were changed, canceled, and delayed. As the protests grew more confrontational outside, the temperature inside the airport rose. The group’s scheduled 10 a.m. flight to Munich was taken off the board, but after frantically waiting all day, that night Charlotte Sproul spotted a flight for Dusseldorf, Germany, boarding with seats still available. She pushed forward and managed to get seats for the 17 members of the tour group who had made flight reservations through the travel agency.

The flight made it off the ground that night, but took off too late to make it to Dusseldorf before the airport closed for the night. They ended up in Cologne, Germany, spent the night at the airport Holiday Inn, and found a flight from Munich to San Francisco the next morning.

John Fossum and his wife made it out a day later on a KLM flight through the Netherlands. He returned with his interest piqued; Fossum says he was deeply interested in the Middle East before visiting, but that after seeing both Israel and Egypt in January, he’d love to return, maybe as soon as next year. The travelers got out of the country at the right time, but there’s still the sense that there’s more to the story.

A few weeks after Fossum got home, on a day when Mubarak’s departure was evident, he attended a lunch in honor of the Egyptian investment banker Mohamed El-Erian. Many of the attendees were Egyptian-Americans, and Fossum says he’s “seldom been anyplace where there was such a sense of jubilation.”

“This whole concept of the Arab Spring, it’s fascinating and it’s kind of rejuvenating,” Fossum says. “I don’t know if strategically and politically this is good for the United States or not. But I think it’s good for the people, and good overall.”

Like Fossum, the Sprouls also have carefully followed news from the revolution. They give talks about their trip to Egypt, and Bob invariably starts the lecture by pointing out that before traveling there, he knew nothing about the country—it was one of a handful of places, he says, that he had put an X through on his map of the world, meaning that he was not interested in visiting it.

Now, he says, he can’t get enough of it. Months after their return home, the Sprouls can slip into a half-hour discussion of the Egyptian economy, GDP, population statistics, politics. His fascination with the life of the Wall Street Journal reporter—to speak the language, to understand the crowd, to have the courage to charge into the protest to get the story—is evident. “If I were 31,” he says, “I’d be a war correspondent.”

Both Sprouls say they want to return, the sooner, the better.

“I tell people, if you have a chance to go to Egypt, go now,” Charlotte Sproul says. “It’s not any more dangerous than it was before.”

Bob quickly agrees.

“I’d like to go back,” he says. “Finish off our trip.”

In June, Charlotte led a completely different type of trip, to France: a barge trip on the Seine.

And how was that?

“It was a little boring,” Bob says.