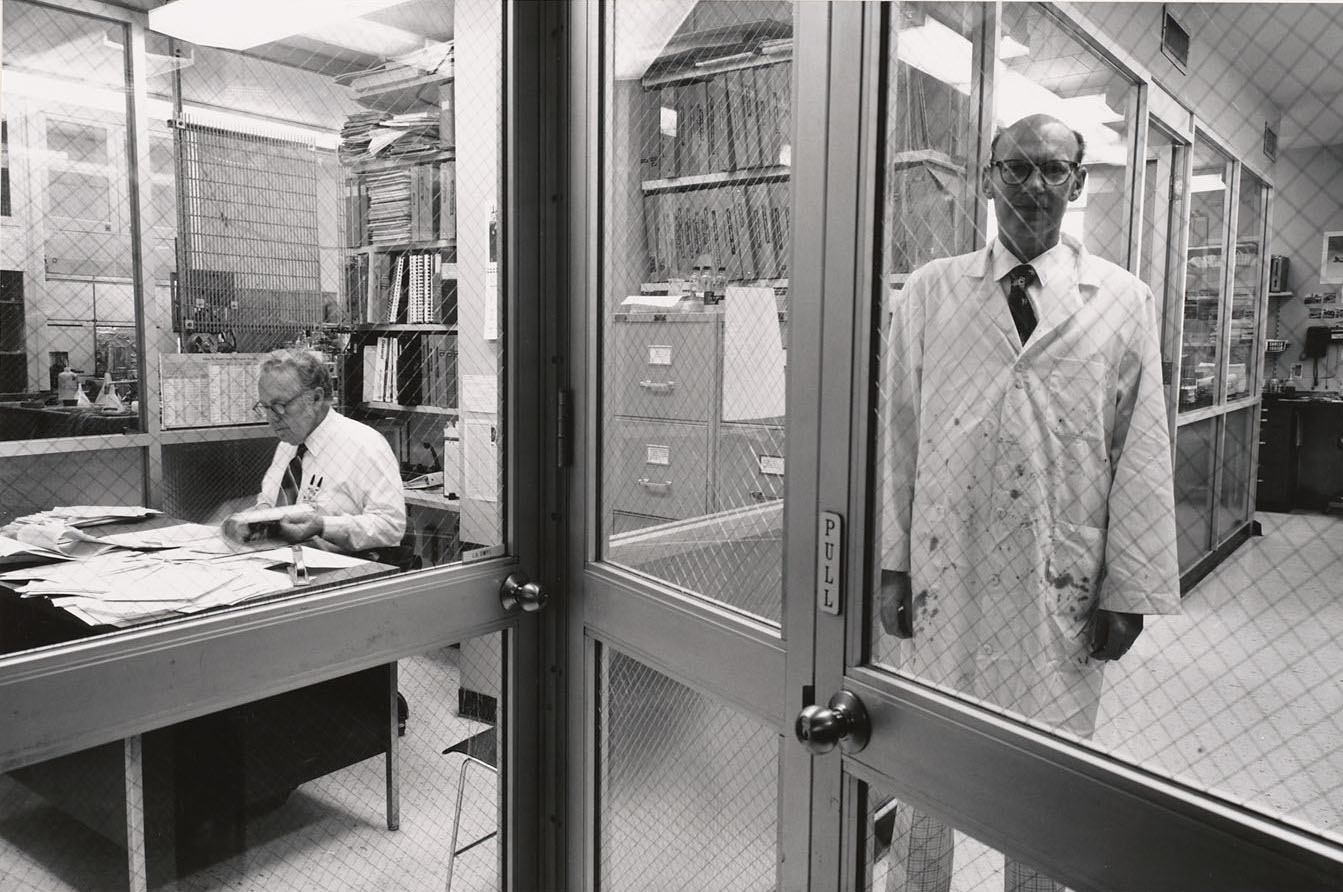

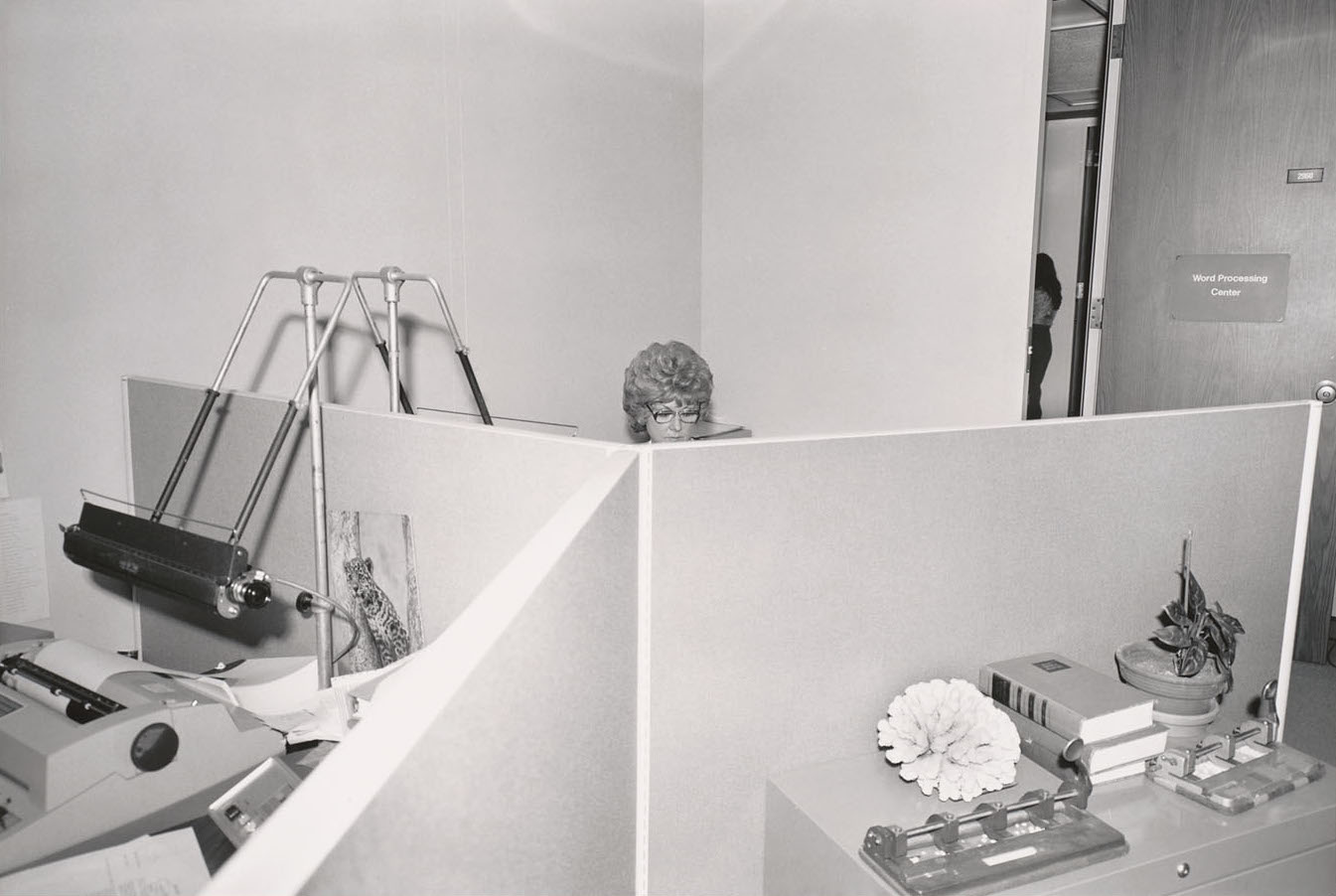

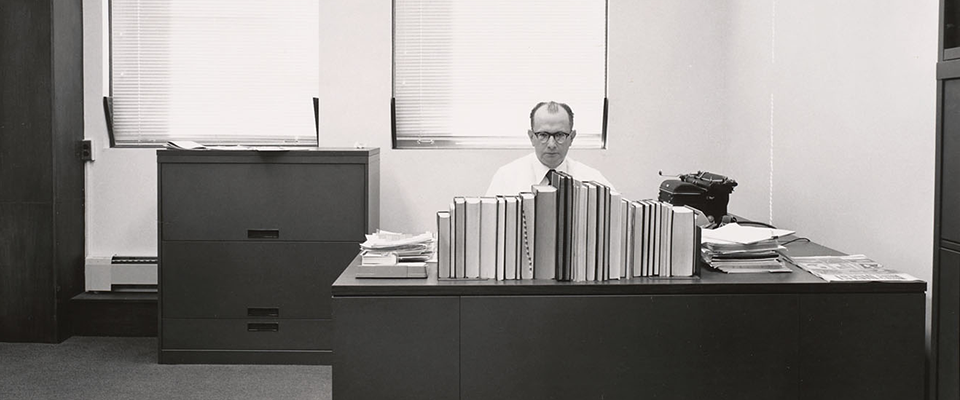

Photographer Chauncey Hare trained his lens on the modern corporate hellscape.

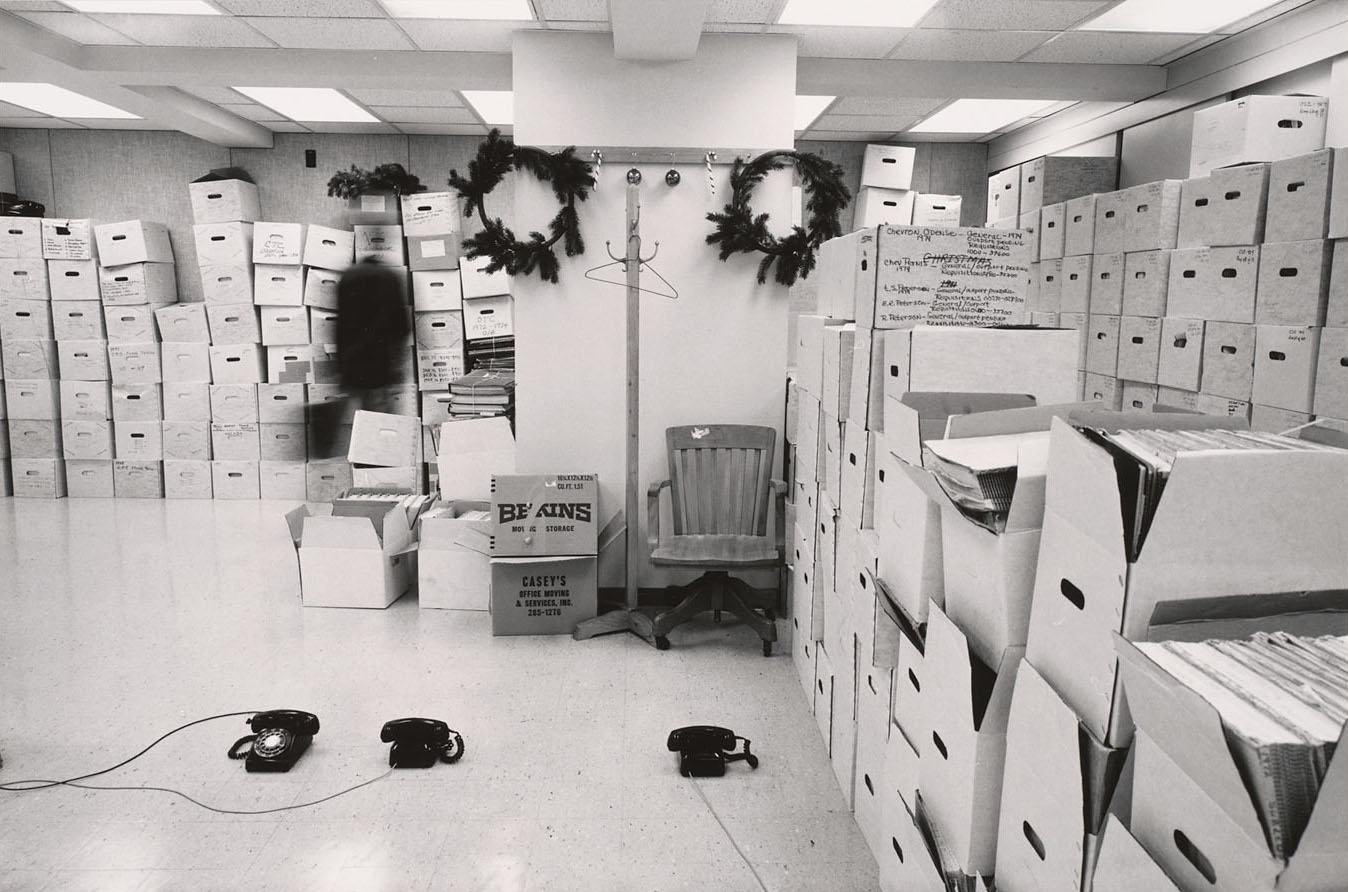

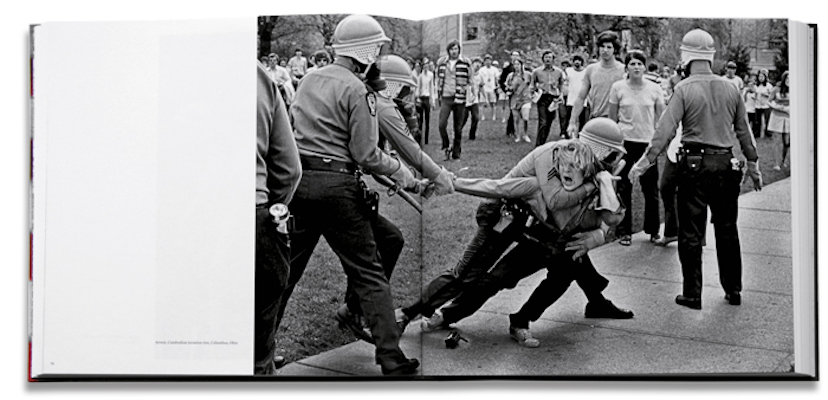

“Chauncey hardly ever cracked a smile,” said the Bancroft Library’s pictorial curator, Jack von Euw, of photographer Chauncey Hare. And yet, there is humor in his work—albeit dark humor. His photographs of dreary office scenes recall the old joke about a man who goes to Hell and discovers a room full of people drinking coffee, waist-deep in excrement. “This isn’t so bad,” the sinner thinks. Then an announcement comes over the loudspeaker: “Coffee break is over! Back on your heads!”

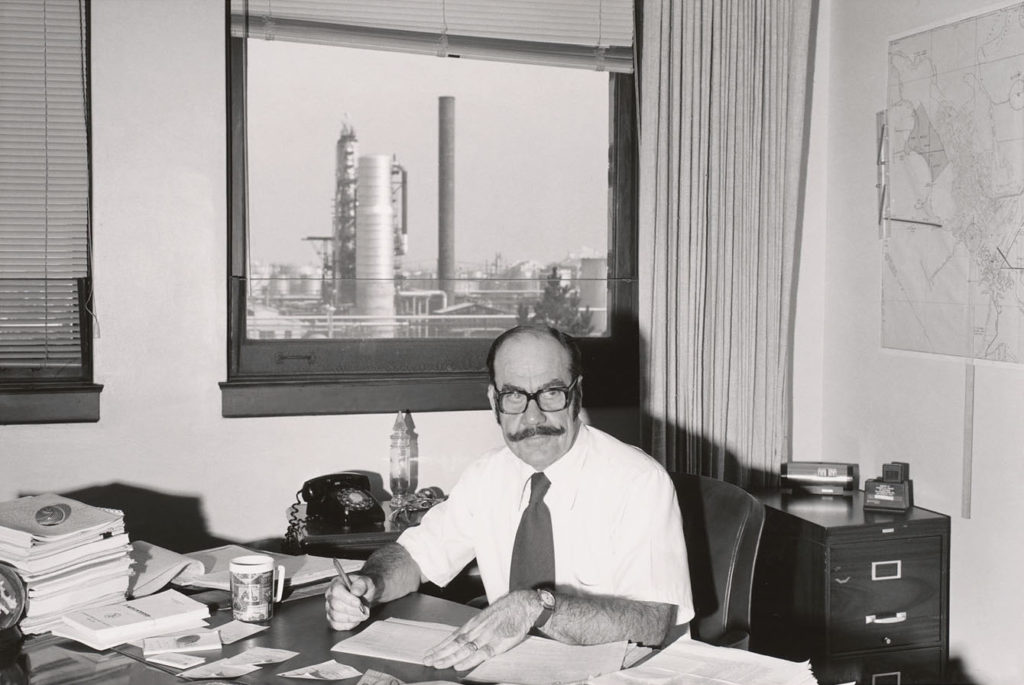

Hare, who died in May, was a chemical engineer for Standard Oil. He took up photography in 1962 as a way to ease the psychic pain of the corporate grind, and ultimately was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship three times. Like Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank before him, Hare sought to show America as it truly was. The photos of rooms stacked with file boxes and scenes of dead-eyed workers lunching at their desks were both therapy and a form of resistance. He drew inspiration from the 1960s protest movements in Berkeley, where he lived.

“I think it’s the most important collection I ever brought,” said Bancroft pictorial curator, Jack von Euw. “And we almost lost it.”

Hare’s hatred of the corporate world was nearly matched by his disdain for the art world. He never sold his images, thinking it inappropriate to make money on photographs of people in distress. (Von Euw first met Hare in 1979 on the steps of SFMOMA, where the photographer was protesting the display of his own work because the tobacco company Philip Morris was sponsoring the show.) He required that his images be accompanied by the following caption: “These photographs were made by Chauncey Hare to protest and warn against the growing domination of working people by multinational corporations and their elite owners and managers.”

When it came to his archive, he was insistent that whoever took possession of it never sell it to corporations. Hare told von Euw that he planned to burn the work if he couldn’t find a satisfactory place that would agree to his terms. Von Euw persuaded Hare to consign it to the Bancroft rather than to the flames. “I think it’s the most important collection I ever brought,” said von Euw, a nearly 30-year veteran of the archives. “And we almost lost it.”

By 1984, Hare was done with photography, having found a more direct route to helping his subjects: He became a therapist for the office-weary. This time of year, as many of us settle back into the tedium of our regular routines after summer, Hare’s work feels particularly poignant. You can almost hear the voices of the “elite owners and managers” crackling over the loudspeaker: Back on your heads!

These photographs were made by Chauncey Hare to protest and warn against the growing domination of working people by multinational corporations and their elite owners and managers.

Standard Oil, Richmond, CA, Chauncey Hare Photograph Archive, BANC PIC 2000.012.14.004–ffALB, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley