Turns out men have a biological clock, too

As I creep into my 30s, my mother keeps pestering me about when I intend to reproduce. As she constantly reminds me: I’m not getting any younger. The tick of the “biological clock” is more often something women worry about. But new research suggests men who delay fatherhood also face reproductive risks.

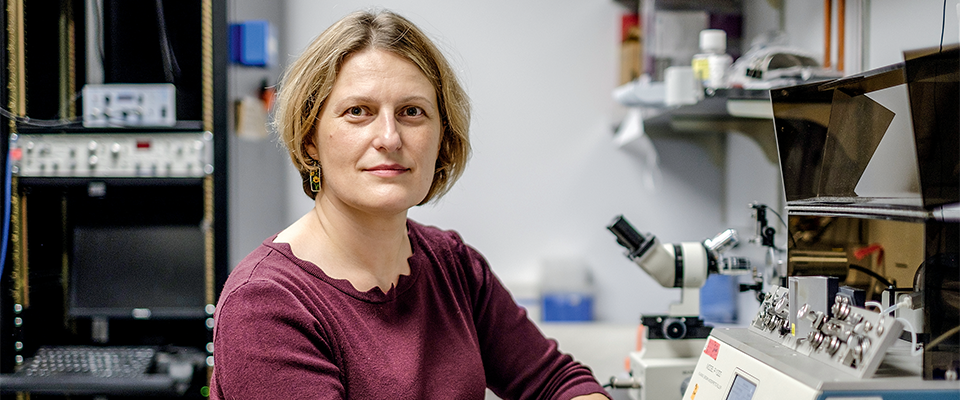

In a small dark lab at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Thomas Schmid looks into a microscope and counts green and blue fluorescent dots inside a human sperm cell. Each color represents a different chromosome, he tells me. A blue dot represents the X chromosome; a green dot represents a Y. A sperm cell that has more or less than one chromosome, he explains, increases the risk of birth defects. “What we’re doing is looking at what [chromosomes are] inside the sperm,” says Schmid. “This way we can determine the proportion of sperm with the wrong chromosomes. Fertilization with such sperm [could] produce pregnancies with Down Syndrome and other abnormalities.”

Schmid is part of a team of scientists at the lab who’ve spent years studying the role that health, diet, and chemicals play on the quality and fertility of sperm. Their current research started in the mid-90s when Andrew J. Wyrobek, senior scientist and head of the Department of Radiation Biosciences, teamed up with Berkeley epidemiology professor Brenda Eskenazi in the School of Public Health to study how genetically defective sperm affect a man’s ability to have a healthy child-particularly in populations of men exposed to hazardous chemicals.

In looking at the effects of chemicals, the researchers also conducted studies to understand common factors affecting sperm-such as age and diet. “You have to take all [common factors] into consideration,” says Schmid. “So you can establish that it is indeed the chemical you’re studying that is affecting the sperm.”

They analyzed sperm samples from about 100 healthy, non-smoking men between the ages of 22 and 80 and found that, contrary to common belief, sperm quality deteriorates with age. Their report, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last summer, found that the proportion of sperm with fragmented DNA and gene mutations causing dwarfism increases by about 2 percent each year (no such correlation was found with Down Syndrome). Earlier research by the group also found that sperm fertility starts dropping in men in their 20s and continues to diminish for the rest of their lives. Sperm also slow down and lose their sense of direction as a man ages: 75 percent of the sperm from a 22-year-old man are strong and able swimmers, in contrast to only 15 percent of the sperm from a 60-year-old man.

Wyrobek says the ten or so methods used by his team for studying sperm-including examining the sperm’s swim speed, shape, and genetic makeup-will open all kinds of doors for future research. “Now comes the question of what risk factors damage our sperm, and we’re just starting on that,” he says. “Whoever has a question: Does this medication have a detrimental effect on sperm? Which occupational exposures damage sperm? Are there lifestyle or dietary factors that affect sperm? These are now studies that people can do.”