Oakley Hall was the most famous writer you never heard of, and one of the best writing teachers who ever lived. Plus: Warlock excerpt

It was at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers’ conference five years ago that I found myself sharing a picnic bench at the staff dinner with the following literary luminaries: Michael Chabon, who was holding two of his sons at once, little blond replicas of himself; Alice Sebold, in black diamond-shaped glasses; Amy Tan, her two Yorkshire terriers fighting in the pack strapped to her chest; and dreadlocked Anne Lamott, who had earlier that day said that if you don’t carry a notebook for jotting down ideas, god will give them to someone else.

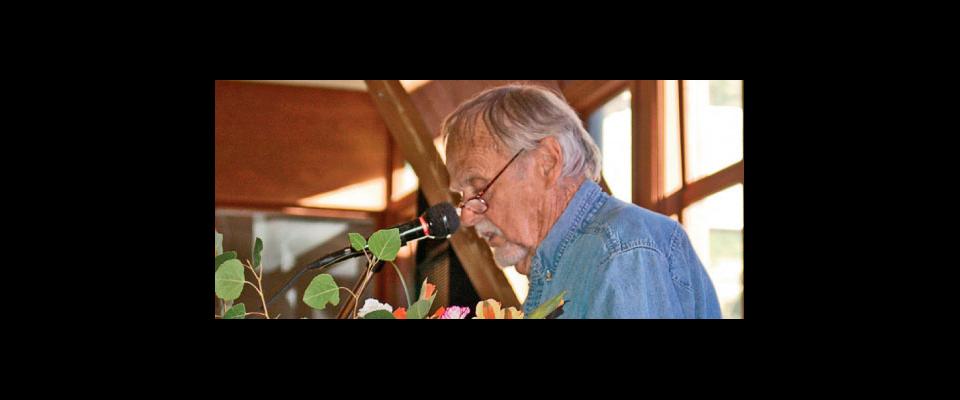

At the end of the bench was Oakley Hall, with his white goatee and thinning white hair that never quite looked combed, and a sly, small grin. Few would recognize him among these luminaries, his “literary offspring,” as Amy Tan styles herself. But all of these writers, and many more, called him their teacher. Tan was with him the day before he died last May at the age of 87. No fewer than three memorials are considered sufficient for everybody he touched to pay their respects.

Hall wrote close to 30 books, novels and mysteries and two on the craft of novel-writing. The one that made his reputation began when he found that his grandmother had lived next door to the biographer of Wyatt Earp. Westerns then were mostly a species of pulp lit about schoolteachers and whores with hearts of gold and men in white hats and black hats. Hall came up with Warlock, whose hero’s hat is a more interesting shade of gray. It was a finalist for the 1958 Pulitzer Prize for fiction (beaten out by James Agee’s A Death in the Family). It was made into a movie of the same title starring Henry Fonda (not a very good movie, alas) and did get the author into the Cowboy Hall of Fame (the then-chancellor of Berkeley himself wrote to congratulate Hall about that—he graduated from Berkeley in 1943).

Thomas Pynchon and Robert Stone are among the cult-like fans of that book. For the back cover of the 2005 re-release of Warlock, Pynchon is quoted: “Tombstone, Arizona, during the 1880’s is, in ways, our national Camelot: a never-never land where American virtues are embodied in the Earps, and the opposite evils in the Clanton gang; where the confrontation at the OK Corral takes on some of the dry purity of the Arthurian joust. Oakley Hall, in his very fine novel Warlock has restored to the myth of Tombstone its full, mortal, blooded humanity.” And there are contemporary fans, even a rock band called Oakley Hall—its lead singer, Pat Sullivan, is a fan of Warlock too.

Many more books followed, including The Downhill Racers (made into a movie with Robert Redford). He never quite achieved the lasting popular recognition of many of his own students, and once referred to himself as the most famous author nobody had ever heard of. “I’m a good writer who nobody pays attention to,” he told a reporter ten years ago. “But I don’t want to be Philip Roth. All that pressure. I do wish more people read my books, but when you are better known, there are so many expectations.”

Hall’s students include the famous writers on the picnic bench. The year that Warlock came out Oakley and his wife, the photographer Barbara Hall, moved up to Squaw Valley so they could ski all winter and play tennis all summer. “We hiked into a particularly lovely part of the valley and there was a beautiful slightly flat promontory and a deer sleeping in the underbrush. We asked for that lot,” recalled Barbara.

The remote valley was a long way from the publishing world of New York and Hall had the notion of using the ski resort that stood empty in summer to put on a writers conference. He asked a neighbor in the valley, Blair Fuller, a fellow writer (and tennis and skiing enthusiast) who had been the editor of The Paris Review, if he wanted to do it with him.

“We went into it lightheartedly. It was kinda crazy,” Fuller recalled by phone from his home in Tomales Bay. Hall himself was candid about admitting that the now-famous conference began as an excuse to drink and play tennis and lure the suits of the New York publishing world out to California. In his afterword to Writers Workshop in a Book, a compendium of essays from the Squaw Valley Community of Writers staff, he wrote, “At that time, West Coast writers rarely saw their agents and editors without expensive trips to New York.… It seemed to us that we could mount a conference featuring workshops, panels, talks, and readings, with agents and editors on hand, and parties and tennis as a major part of the week.”

He added, “We were aware that the conference ought to include participants whose tuitions would pay our costs.” That first year, 1968, they contacted UC Extension at Davis, which agreed to finance and promote the conference if Hall and Fuller would do the legwork, i.e., strong-arming their writer friends into coming up to Squaw to lead workshops “for really, no money,” as Fuller said. He got Peter Matthiessen, Barnaby Conrad, and San Francisco novelist Herb Gold to agree. Hall had contacts at the Iowa Writers’ Conference, where he had earned his MFA. He invited such writer pals as Robert Stone and poet Mark Strand and they all said sure.

“People tended to say yes to Oakley,” said Fred Hill, a prominent San Francisco literary agent who himself often accepted Hall’s invitations to Squaw. “He was big, brassy and hospitable as hell.”

Novelist James Houston, echoed Hill when he said, “Oakley himself magnetized people around him of a common interest and common spirit. He had great zest for life and a good sense of humor. He loved to tell jokes, sit around and have a drink of wine.”

After some initial tendency toward carousing, with celebrated novelists showing up late and hung over for workshops, the conference soon surprised even its founders by becoming a serious and successful yearly event, with workshops and panels on poetry, fiction, screenwriting, and playwrighting. Hall insisted that the staff writers understand they were not there to preen, but to serve the participants, says Al Young ’69, California poet laureate 2005–2008 and longtime Squaw staffer and board member. “No matter how big a star you might have been away from the conference,” he said, “if you didn’t give your full attention to the students you weren’t asked back.”

Hall and Fuller (who was not active in the conference after 1985) watched, perhaps to their bemusement, as many participants (as they are called) used the mentoring and the contacts to become published authors themselves. A woman named Anne Rice, for example, arrived with some pages about a vampire and left with a Knopf editor and a New York contract. A 25-year-old short-story writer named Richard Ford (who won the Pulitzer for Independence Day in 1996), came up the first year. “Peter Mathiassen took my story out of that workshop and got it published in The Paris Review,” he told me by phone from his home in Maine.

A young and nervous Amy Tan arrived from San Francisco in 1985 with a fistful of short stories that became the bestselling Joy Luck Club. “Oakley was the reason that I found my confidence as a writer,” Tan told the San Francisco Chronicle.

Al Young believes it was Hall’s insistence on teaching structure that accounts for the many successful careers that began not only at Squaw, but at UC Irvine’s tiny but revered (500 students vie for 6 places a year) graduate writing program, where Hall taught in the winter for 20 years. From the beginning the conference and the UC program were symbiotic, the winter program sticking to writing and sending students to Squaw in summer for the publishing end of things. “Oakley’s course on structure was legendary,” said Michelle Latiolais, present co-director at Irvine. “He had a classical education in literature and would ground you in it. ‘Go read your Faulkner,’ he’d say.”

Latiolais recalled being a student in 1984 in what Hall referred to as the “Magic Workshop,” which included Michael Chabon, Jay Gummerman, Louis B. Jones, and Whitney Otto. Latiolais was then working on a novel that turned into Even Now. “He was a big man and he would kind of joyfully yell at you across the English office, ‘Why did you have that character to do that?’ And everybody would hear. And it shaved away the shame.”

Chabon discovered Hall’s rigorous side for himself when he showed up at Irvine with 110 pages of a novel and gave them to Hall to read. “‘I don’t like it,’ he said, sliding my pile of well-typed crap across his desk at me as if it were picked-at remnants of a meal that had been poorly prepared from inferior ingredients. He had a craggy Western face and a prize-fighter way of looking up from under his brow at you and the pugnacious, warm eyes of a tough-guy priest in an old Warner Brothers movie.”

Recalled Chabon, “I might have told him, ‘Hey, give me a break, old dude, this is my first try, what the hell do you want?’ What I said, awash in the dread and embarrassment of the embezzler caught or the fraud unmasked, was, ‘You’re right.'”

Hall could also make a writer feel like a million bucks. “He had perfected a wonderful sound that was like an ‘hmm’ or a ‘hum’ that made you feel that you had come up with such a novel idea that no one had ever thought of before,” said Oakley’s daughter Sands Hall, a novelist actively involved in the conference. Her sister, Brett Hall Jones, is the director. (The Halls also have a son, Oakley “Tad” Hall III; another daughter, Tracy; and there are seven grandchildren.)

Richard Ford learned more than the craft of writing from Hall. “Oakley, much as he taught me how to be a better writer, also taught me how to conduct myself. Where to put my ego, so that I was not writing for egotistical reasons. I would try to make myself more like him—have more humility toward my vocation.”

He also learned a few things about marriage from Hall. In the winter of 1969 at Irvine, Ford remembers, Hall offered him a ride home in his old Volvo, and they discovered they were neighbors. Ford, who had married his wife Christine that year, spontaneously asked Hall and his wife Barbara to dinner. “They were the first grownup adult people we’d had to dinner. There was a passionate decorousness between them. A huge civility. I learned from Oakley the way you put yourself into the world as a man married to a woman. After that, Christine and I looked to Oakley and Barbara to learn how to be married.”

The Halls were married for 63 years. Ford is now in his 40th year of marriage to Christine. He and Hall remained friends, exchanging letters and later email twice a month for 38 years.

People liked to stay in Hall’s life, once in it. Writers who had made it, like Janet Fitch and Anne Lamott, Amy Tan, and Sharon Olds, who wrote a poem for Hall when he died, come back year after year to lead workshops and return the favor. Tan now has a house on the Truckee River a few miles from the conference, and hosts the staff party, as well as serving on the board.

She was with Oakley Hall in Nevada City, at the house of his daughter Brett Hall (who is married to the novelist Louis B. Jones) the day before he died of cancer and renal failure. “The medicine induced a terrible restlessness, and when it seemed worse, we read to him from the novel he had just completed, a story about Guinevere and the Knights of the Round Table, and in this one, Guinevere is vindicated and not reviled. At times, Oakley issued a grunt of approval—or was it a groan that the passage just read should be revised?”

Tan decided to make dinner that night. “Cooking, I realized, was the only way I could leave Oakley that night. Doing the mundane amid the momentous. To sauté up garlic, wash the last dish, dry the last wine glass, to give him a kiss on the cheek, then get in the car with Lou and drive down the road knowing I would not see him again.”