In Ethiopia, Timothy White and his colleagues have found some of our nearest relatives, and powerful evidence that we all come from Africa.

During lunch at Chez Panisse, Tim White draws a map of places I should visit in Ethiopia, on the paper table mat. The famed professor agrees to rendezvous with me at the National Museum in Addis Ababa after he returns from his upcoming field trip. Watching him sketch the suggested route, I’m fixated on the areas he zigs around. Earlier, before I could specify the dates I’d be in Ethiopia, White had refused to allow me to visit him in the field. “There’s no way you could find your way in or out,” he’d said. Taking this taunt as a challenge, I analyze his approved route now unfolding on the table.

White is in no rush to attract others to his hunting grounds. His findings, when made public, are subjected to scrutiny by competitors. He and his team often take six careful years from discovery to publication. White is a treasure hunter competing in perhaps the nastiest, most competitive field in academe.

How do I describe Berkeley’s star paleoanthropologist, someone whose profession I can barely pronounce? To become a top predator, White has mastered anthropology, archaeology, biology, dentistry, ecology, ethnography, and more. Simply put, he and his colleagues try to figure out, through the archaeological record, how the human mammal came to be. White’s fingerprints are all over such skeletons as the famous Lucy (discovered by Donald Johanson, et al.); Lucy’s 4.2 million-year-old, big-toothed ape-man ancestor; her 2.5 million-year-old descendant who might have been the first to butcher animals with tools; and the 160,000-year-old Herto hominids, two adults and a child, our most anatomically similar ancestors. White also helped uncover the tracks of three hominids who walked upright for 77 feet in damp volcanic ash 3.7 million years ago. If a Nobel Prize were awarded for the science of human evolution, White would already have won several. A small, balding, bespectacled man, White possesses a wiliness and ferocity that lurk beneath a broad, impenetrable smile.

White’s pen suddenly turns south of Addis Ababa to a ford on the Upper Awash River. “You really should visit the open-air museum at Melka Kunture.”

Lunch comes to a lively close. The paleoanthropologist and the reporter see eye to competitive eye on human nature. A happy handshake is accompanied by forced cheer: “See you at the National Museum!”

My first stop in Ethiopia is the Museum of Melka Kunture, as Professor White had recommended, but with a twist that he hadn’t. I hire a guide named Tshoman, who says he knows White and has recently helped caravan his team to the Afar Depression down the Awash River. Early one morning we drive south out of Addis Ababa, a bustling city filled with poverty and political intrigue, and pass through a treeless landscape to reach Melka Kunture.

The museum consists of several excavated sites on the Upper Awash River where ancient hominids scavenged. Primarily an open-air museum, it includes explanatory exhibits housed in round huts built in a traditional Ethiopian style.

Some 30 million years ago, three tectonic plates yanked apart a 4,000-mile rift in the Earth’s crust. Two of the gaps soon filled with water, forming the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. The third gap, Africa’s Great Rift Valley, will eventually flood as well. Active volcanoes along this rift created silica-rich rocks that fractured smoothly and left the sharp edges humans used to make our first tools. The museum’s highlight is an elevated site close to the river where humans butchered hippos 750,000 years ago.

Bull hippos can weigh more than four tons. They spend the day in water and come ashore at night to graze on grass. It’s hard to completely swallow what the local guide is saying: that humans who happened to be nearby scavenged hippos that had conveniently expired. It seems as likely to me that people might have excavated and disguised a pit and then stabbed to death a hippo that fell in when it trundled ashore.

Bones of ancient horses, wildebeest, and giraffes, also butchered, lie at nearby sites, but basically the Awash River had served up hippo here. “How close were the forests?” I ask the local guide. Far, far away, he motions. “Here always grassland,” he says. White has sent me into a hippo cul-de-sac.

Now seems a good time to pop the question. I’ve brought a map of the Afar Depressio—Ñthat parched, sunken, sediment-rich region of the Middle Awash where millions of years’ deposits lie exposed in tectonically warped strata. Casually, I pull out the map and ask Tshoman, “So where did you drop Tim off?” Tshoman studies the map and points north of a big bend in the river.

“Could you find your way there again?”

“Sure, but you don’t want to go. This is like heaven,” Tshoman says, gesturing above to the mild sky. “It’s like hell there.”

Professor White waits in front of the National Museum and escorts me around to the lab, which has only a back-door entrance. Sitting behind a temporary wall in the museum’s ground floor, the lab occupies a small space perhaps 50 by 131 feet. White introduces the men sitting at workbenches, most Berkeley-trained, busily cleaning and categorizing finds from the recent trip. “This is Dr. Berhane Asfaw, this is Dr. Yohannes Haile-Selassie, this is Dr. Gary Richards, this is Dr. …” A doctor of geology detects the magnetic polarity remaining in rocks; a doctor of geochronology looks for the unique chemical imprint left in ash by each volcanic eruption. So many specialists are working so ardently in such a small space, it feels as if I’ve entered a surgical operating room. Soon I realize this is the hominid morgue to end all morgues.

Professor White, together with his Ethiopian protégé and now colleague Dr. Asfaw, have uncovered more evidence than any other paleoanthropologists to support the hypothesis that Homo sapiens first appeared in Africa and dispersed from there throughout the world. Studies of the human genome validate White’s conclusions that modern humans evolved and spread out from Africa alone. In February, geneticists reported in Science their detailed analysis of 938 unrelated individuals from 51 populations at 650,000 common single-nucleotide polymorphism loci. I don’t know what this means, but the resulting population substructure map indicated that Homo sapiens spread, over the last 100,000 years, from a home base in sub-Saharan Africa “consistent with the hypothesis of a serial founder effect with a single origin.” Other genetic studies conclude that an ancient band of explorers departed from what is now Ethiopia to colonize the world.

Here in the lab, reassembled bones from previous expeditions are placed in lab drawers that indicate the bones’ former position in the strata. Curated alongside the hominid bones are remains of lions, rats, elephants, fish, hippos, mice, bats, gazelles, insects, and plants. The meticulous organization of these drawers would make an upscale haberdasher proud.

White opens one drawer, extracts a smooth-faced black rock, and places it in my hands. “That’s a 2.5 million-year-old tool. The oldest tool ever found is 2.6 million years old.”

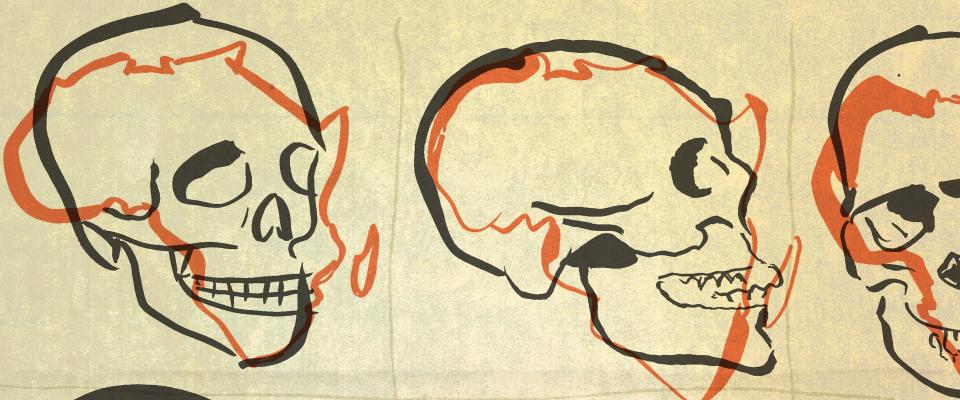

White’s tone switches from academic to exuberant when handing over the skulls of ancient humans. Just in this lab, there is a much wider variety of fossilized skulls than I ever imagined. Thick and thin skulls. High brows and wide brows with heavily protruding ridges. Others have a bony spine atop their cranium to which powerful chewing muscles were once attached.

“Look at this!” White says, holding up Homo sapiens idàltu (idàltu means elder), the restored adult skull of our nearest ancestor. The skull, found in Herto, is exceptionally long and has a slighter larger cranial capacity than the average human’s today. “This was one big dude!” Indeed, the Herto head is bigger than Herman Munster’s.

Even more important than size in the morgue is morphology. For example: Do the bones at the base of the skull indicate that this hominid leaned forward or more comfortably walked upright?

And teeth! If you’re a recent human ancestor who wants to have your teeth reconstructed, the lab in the back of Ethiopia’s National Museum is the place to go.

The paleoanthropologists here are meticulous hard workers, and none more quietly so than Dr. Berhane Asfaw. Asfaw spotted the first piece of the 160,000-year-old Herto child’s shattered skull. Over the next three years, he patiently removed the sandstone cemented to each of the 200 scattered pieces and puzzled the cranium back together using such clues as the microscopic impressions left by the child’s individual blood vessels.

Professor White hands me the Herto child’s skull. The 2.5 million-year-old stone tool felt like … well, like a rock. But running my hand over the cranium and feeling its polish, my own cranium vibrates down through my spine. “Look at these,” White says, taking back the skull. He points out many tiny, intentional scrapes around the circumference of the skull and between the forehead and ears. Indicating the back of the cranial base, White says, “Someone broke the skull here,” and, pointing to the rough gouges around the eyes, “then defleshed the softer tissue with deeper cuts here.”

“Did they eat its flesh and brains?”

“We don’t know.” He turns the skull over again. “But here someone widened the base, maybe to scoop everything out.”

Gingerly retrieving the skull, I again run my hand all over the cranium. Even the edges where the skull was broken off from its skeleton are polished. “Why was it polished?”

“Maybe it was just handled a lot,” White replies with a smile. He’s daring me to imagine how it might have been handled.

“But whether it was deliberately polished and worn smooth from repeated handling,” I ask, “you think it was part of some funerary ritual?”

“Funerary ritual, but not a funeral. We didn’t find a single other hominid bone near the site.”

“No other bones?”

“Butchered hippo bones, but no other human bones.”

The scientists in the lab have heard and themselves told this story many times, but still they radiate pride when hearing how their team discovered the hominids anatomically closest to us. The Herto find put the final nail in the multiregional evolution coffin. We all come from Africa.

Most scientists agree that we became physically modern some 150,000 years ago, but there’s no consensus on when Homo sapiens developed language. While thanking Professor White and leaving, I jokingly ask what he thinks were the first words spoken by humans. Without hesitation he replies, “Give me!”

The sensation left by the Herto child’s skull lingers with me. When the finds were displayed to the public in 2003, White suggested that the marks and polish on this skull provided some of the earliest documented evidence of ritual burial. These patterned cut marks, I muse, must have helped transmit a tradition, a custom, a cultural identity. Were they intended to convey magical power over death? Why else carry around as a totem a human who had prematurely perished? Perhaps the child was young royalty. If so, was his skull’s presence supposed to transmit magic from an afterworld?

I fly to Northern Ethiopia where I’ve engaged a helicopter company to whisk me east over the highland peaks and down 9,000 feet to the Afar Depression. My preferred landing spot: anywhere near where my guide, Tshoman, pointed when we were in Melka Kunture. But next morning, the helicopter company’s agent says we can’t go. There’s just not enough time to get approval from all the Afar clan chiefs.

After a string of my protests fail, I climb, heartbroken, into a four-wheeler brought north by Tamrat Giorgis, a new friend who’s editor of an Ethiopian weekly. I kick off my shoes and we drive south back to Addis Ababa on Ethiopia’s Route 1.

Despite Ethiopia’s image as famine ridden, the steep hillsides are artfully cultivated with crops. Men and women stride energetically along high ridges. Professor White never mentioned bipedalism as a defining human trait. Odd. And why was Asfaw sequencing the big skulls behind his desk? Perhaps he’s piecing together an early, robust human.

The car stops, Giorgis jumps out and runs eastward up the hillside. We’ve reached a sharp bend bordered by a thin ridge that he scales in no time. “Up here!” he calls.

Climbing up the ridge barefoot, I reach the western rim of East Africa’s rift. Straight down two miles is the Afar. With no obstructions, we can see the muddy Awash River making a big bend in the middle of a lunar landscape. Above us on the ridge, a large family of monkeys graze. “Gelada baboons,” Giorgis says. “Endemic.”

The Afar is a wasteland. But 150,000 years earlier, it was dotted with forests and lakes brimming with fish, crocodiles, and hippos. Humans feasted on the fauna they butchered with sharp obsidian blades bestowed by the smoking mountains. A human population could prosper below, then one millennium (perhaps when the bottled-up valley floor could no longer support so many tribes) make a trek up to the highlands.

What kind of humans? An aggressively symbolizing, reflective breed that held its heads in high regard.

As I keep climbing for the steepest perspective, the gelada baboon family retreats. A baby clings to its mother as she scampers over the cliff to a vertical haven. One juvenile stands his ground, gazing. Down the ridge rumbles the largest member of the group, a male sporting a red chest plate and a mane so long it doubles as a cape. The male’s eyebrows are white and frowning. He scolds the juvenile to join the group.

Our ancestors who emerged from the rifts below were bigger than us and perhaps braver. Their braincases were more capacious than ours—why do scientists today resist calling them smarter? No one would hesitate to label them dumber if they had smaller brains. So smarter, bigger, upwardly mobile humans carrying a complex social culture based upon a peculiarly human sense of vulnerability and invincibility clambered out to conquer the planet.

The juvenile gelada takes one last inquisitive look at the Homo sapiens, then gives in to family pressure and disappears over the cliff.