How economist Paul S. Taylor pioneered the use of photography as social documentary.

As Paul Taylor and I topped Strawberry Canyon and turned west, a pastel sunset spread across the sky. Below us was the San Francisco Bay, with a clear view through the silhouetted Golden Gate Bridge. In the soft, oblique light, Taylor’s face was bathed in that warm glow that I was seeking.

I had been photographing Taylor for many years. As we strolled arm and arm through the campus he stopped every few seconds to clear his lungs of mucus and spit—an insidious legacy from the mustard gas barrage he had suffered as a Marine Corps second lieutenant and platoon leader in the trenches of France during World War I.

Pausing for pictures at favorite sites, Taylor recalled episodes from his life with Dorothea Lange, the great social documentary photographer who had died 17 years earlier. At the old hollowed-out oak beside Strawberry Creek in the Faculty Glade (now gone), Taylor pointed to the cables holding the withered limbs in place and offered his sympathies. The old tree and he had a lot in common. Finally we reached the Bancroft Library. The entire staff paused from its duties and snapped to attention. Researchers put down their pencils. “Is that Taylor?” one whispered. “I thought he was dead.”

Taylor was one of the towering figures in California intellectual life. You cannot write the history of agriculture and farm labor without referring to him. You cannot comprehend the full meaning of academic freedom and persistent scholarship without reflecting on his career. And, as I would later learn, you cannot consider the story of documentary photography in California without acknowledging the role that he played, not only as mentor, but as a photographer whose work preceded Lange’s by a decade.

Paul Schuster Taylor was the type of intellectual whom University of California President Clark Kerr later recalled as “a very unusual breed of what might be called economic anthropologists with an interest in labor problems.” Although trained as an economist, Taylor never allowed the academy to divert him from his primary goal—linking social science with public policy to improve the quality of human life. He broke down the artificial barrier to knowledge separating Ivory Tower from Real Life, while injecting a strong humanistic perspective into a discipline mired in cold, hard facts.

Beginning with his study of the West Coast Seaman’s Union, Taylor filtered archival discoveries through the lens of first-hand experiences accumulated working on the docks in San Francisco. When Mexican immigration reached flood tide in the late 1920s, he traveled from Mexico to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to complete a multivolume record of mass migration as it was happening. During the 1930s, he moved into the thick of farm labor battles, taking his student, Clark Kerr, into the San Joaquin Valley in October of 1933 to compile a documentary history of the strike by cotton pickers—still the largest and bloodiest strike in agricultural history.

When the mass exodus of tenant farmers and sharecroppers from the Midwest brought hundreds of thousands of “Okies” and “Arkies” west to California, Taylor again moved into the field, distilling his research into popular articles that communicated with a wide audience. As field research director for the Rural Rehabilitation Division of the California State Relief Administration, he began producing reports designed to bring action as well as convey information. To accomplish this, he assembled a modest staff and hired Dorothea Lange as photographer, concealing her position on the payroll as a typist—in effect launching the career of one of America’s preeminent documentary photographers.

The misery that Taylor encountered in ditch-bank settlements, Okie shanty towns, and decrepit labor camps moved him to action. Taylor became a champion of the Farm Security Administration’s migratory camp system, in effect, the father of the first federal housing program in the United States.

Although pushed to the edge of his chosen profession, Taylor was at the center of the debate over California’s land, labor, and water policies. He was appalled by the decline of small-scale, family farming, and devoted the last half of his career to studying the Reclamation Act of 1902, a law written to benefit the landless poor, but which had the opposite effect. His research and writing earned the ire of large-scale farmers, who referred to him as “that Grapes-of-Wrathy professor.”

All of this gave our jaunt to the Cyclotron special meaning. But there was something else behind the encounter. We both knew the reason, never mentioned it. At 87, Taylor’s mind remained sharp. But his body was failing.

Taylor had Parkinson’s disease. He kept his shakes to a minimum with heavy doses of L-dopa. He had a heart condition. He walked with a cane, at a top speed of about one mile per hour. He could no longer make it across campus to his north-side home of half-a-century. He had fallen several times. He kept his eyelids open by taping them to his forehead.

Although retired and emeritus, he still supervised students, and worked six hours a day, five days a week. How do you capture the measure of such a man? My idea was to photograph Taylor taking a final glimpse at the campus and region that he had called home since 1919. It was a crude visual metaphor. And with the light rapidly fading, I was feeling uneasy, reassessing my plans.

An eighth-of-a-mile from the vista, I had second thoughts. Marching this frail man out there did not seem so bright. So I put my Buick in low gear, zigzagged around some planters, drove the wrong way on a one-way service road, rounded a building, unhooked a chain-link barrier, ignored a No Access sign, and slowly rolled across a lawn to within 20 yards of a promontory.

After walking Taylor to a bench, I quickly unloaded my camera gear, set up a tripod, took a light meter reading, then turned to check on him. Taylor was smiling, watching.

While I was photographing, we had a curious conversation, centering on my choice of the Cyclotron site. “Why here?” he asked.

I blurted out something about the way charged particles move in a spiral path under the influence of alternating voltage and magnetic fields. I said this was not unlike the path he had followed from the battle fields to a professorship. Taylor seemed to like my idea. Surveying the scene below us, he recalled the odd turn of circumstances that had brought him to Berkeley as a battle hardened combat veteran seeking to recuperate from his wounds.

Born in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1895, Taylor had entered the University of Wisconsin in 1913, embarking on a path that he said “gave the bent to my whole life.” At Madison, then considered the top public university in the United States, he found a stimulating intellectual environment, and was strongly attracted to the university’s controversial and challenging economists—Richard T. Ely, E. A. Ross, and John R. Commons. He found them to be broad-minded rather than narrowly academic, and was attracted by their view of economics not as the “dismal science” but rather as a flexible field of study embracing law, history, sociology, and political science.

His education began when he left Madison. On the basis of a single military science course consisting of weekly close-order drill, Taylor obtained a commission in the Marine Corps and shipped out to France, arriving on February 4, 1918. Two months later mustard gas bombs put him and 95 percent of his platoon in the hospital.

Taylor was sent back to the United States to recover and when a family friend and physician advised that Taylor’s lungs might not withstand the rigors of a New York City winter, Taylor turned down a scholarship to Columbia University and headed to Berkeley to spend a year as a graduate student in economics.

From his Bancroft Library Oral Memoir, which I had packed along for the shoot, I read out loud what he had said of his journey west in 1919. “I can remember coming over the Sierras and down into the foothills and seeing the poppies, and arriving in Berkeley down at the old University Avenue S.P. station with the sun shining pleasantly … I found it interesting, exciting—I didn’t feel at home right away—but it was an interesting place.”

But after he began teaching at Berkeley he knew there was no going back. “I felt the appeals of the Bay and the California landscape.”

Our photo session ended in darkness. On our drive back to his home our conversation returned again to his wife Dorothea, whom he thought of often. At his home, Taylor lit a fire to take the chill off. When it roared, he damped it down with a pot full of water. “The body departs,” I remember him saying. “But the spirit lives on.”

Taylor died six months later. Hundreds of friends, former students, allies, and admirers packed the Faculty Club for a commemorative service. Speakers tried to sum him up. Taylor’s legacy was bound up in the Ph.D. and M.A. theses that he supervised. In the fight against the exploitation of farm labor. In the movement to preserve family farming. In his pioneering scholarship. In his work with minorities generations before anyone else.

Administrators estimated that he had taught 20,000 students during his long career at Berkeley. Journalists recalled the influence of his graduate students, among them several legislators and a long list of prominent intellectuals at major American Universities, and two in particular: F. Ray Marshall, who become a secretary of labor, and Clark Kerr, who served with distinction as president of the University of California. Photographers praised his 30-year marriage to photographer Dorothea Lange, their remarkable union of creative intimacy, and their landmark collaboration.

And then, in an offhand remark, a former student mentioned that Taylor had photographed in the fields during the 1920s, while he was conducting field research for his Mexican labor series.

To photograph with a documentary eye in the 1920s among farmworkers or any other such group in California was to break dramatically with prevailing intellectual norms. Documentary photography would remain largely intuitive and undefined for another decade, until Taylor and Lange ventured a working definition stressing an exploration of the human condition, shining a light on the world’s ills, attempting a deeper commentary on life, holding up a mirror to society, serving larger social matters (as opposed to pure art or commerce), bearing witness, and making a difference.

I tracked down Resa Tansey, the Taylor student who mentioned his early photographic work, and who had written her M.A. thesis/photo essay under his supervision. She held his old negatives in her Oakland hills darkroom, where they still resided in old shoeboxes.

The story behind that work took decades to unravel. It shows the range and depth of Taylor’s intellect and places him front and center in any reconstructed history of photography in the Golden State. It also provides a comprehensive and sympathetic snapshot of Mexican labor at a time when it was swamped in clichés and stereotypes. Most importantly, it adds another layer of understanding to Taylor’s relationship with Lange. A lesser human being might have promoted his work. But after Taylor met Lange—as he said, “found his photographer”—he had no reason to photograph.

Taylor had become interested in photography while convalescing from his mustard gassing. Reflecting on the grainy, poorly focused images shot with a Vest Pocket Eastman Kodak camera, he found a communicative power that surpassed all of the words in all of the letters he had written back home. His interest further deepened after becoming an assistant professor in the Berkeley economics department, where he gained awareness of the way Paul Kellog and Survey Graphic magazine were advancing the idea of illustrated social science scholarship.

Survey Graphic exposed Taylor to the work that Lewis Hine was doing among child labor and that Jacob Riis had already done in the New York City tenements. Energized by what he saw, Taylor began to explore more deeply the history of photography and its application to his field of interest—labor economics.

In 1926, when the Social Science Research Council funded Taylor’s proposal to produce his multi-volume Mexican Labor in the United States monograph series, Taylor realized that his subject merged contemporary history with journalism. This called for more than the usual methods of academic enquiry. Hardly content to sit in dusty archives, Taylor realized that he would have to get out among the immigrants, obtain on-the-spot oral interviews, observe conditions up close, and use his camera as a form of visual note-taking.

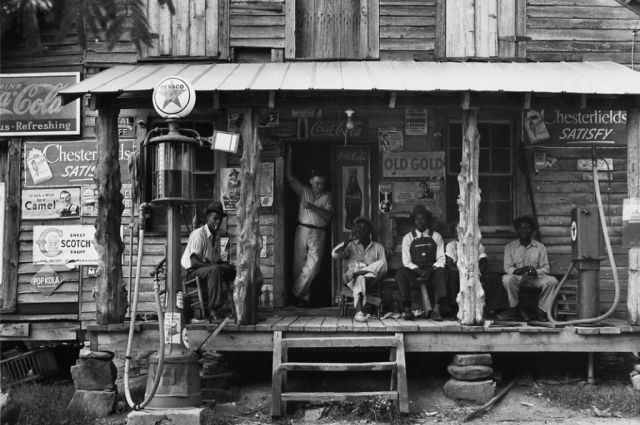

Taylor photographed Mexican immigrants in their peasant villages and ejidos (communal lands), the sugar beet fields and processing plants of Colorado and Utah, the steel mills and meat-packing plants of Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, and the lush farm lands of Arizona and the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. His most challenging photography came in Southern California, especially the Imperial Valley.

Carved out of the raw desert 80 miles east of San Diego, the valley was a place of vast potential and extreme social stratification. Farming was controlled by Anglo owners, many of them absentees, with Mexican laborers, who constituted about one-third of the population, handling most of the field work. “What I saw hit me in the face,” Taylor explained 50 years later.

Taylor’s approach was casual, direct, and sympathetic. Appearing to be no more than a harmless gringo, Taylor was received warmly by labor contractors, welcomed into the cabins of field hands, taken to lunch at the Benito Juarez Society, and allowed to roam freely in the colonias and barrios.

Under these conditions, his small, handheld camera proved especially valuable, allowing him to compose scenes documenting the intimate details of life as well as the pride and struggles of people living on the bare margin. Modest as these efforts were, they placed Taylor in the forefront of changes that were inaugurating a new era in photographic realism. Photography became a keystone in his quest to “find another language” for the social sciences, to move people to action, and to overcome the great sin of his discipline: “the divorce of it from reality.”

By the time he resumed teaching at Berkeley in the fall of 1929, Taylor had about 450 negatives, which he planned to print and integrate into all 13 monographs in his Mexican Labor series. As public opinion raged back and forth in 1931 over the issue of Mexican repatriation, Taylor shed light on the “Mexican Question” by writing a comprehensive article on immigration. After assembling his notes, he printed dozens of his photographs, wrote an accompanying essay, and in March, shipped the package off to Survey Graphic.

Integrating words and pictures into a dramatic and effective narrative, the article, titled “Mexicans North of the Rio Grande,” appeared in May, along with six images by Taylor and four by Ansel Adams, a figure never before associated with the beginning of documentary photography.

The essay stimulated more photographic work, which Taylor undertook during 1932 while studying in Mexico on a Guggenheim Fellowship. When fellow historian Leslie Simpson showed Taylor a new Rolleiflex twin-lens camera, Taylor retired his old Vest Pocket Kodak, and quickly mastered the new photographic technology. “I took more pictures,” he said, “and with the products found ways of persuading academic publishers to print some of my photographs along with my text.”

Taylor broadened his focus beyond Mexican labor and began photographing in the cities, among the unemployed, the down-and-out, and the San Francisco longshoremen, who were then engaged in an extensive organizing campaign. He also inaugurated two other cornerstones of documentary photography. He took extensive notes on the situations he encountered, with particular attention to vernacular expression, so that images and text could be better linked in publications. And he gathered massive amounts of on-site material, ranging from fliers and newspaper clippings to posters and anything else that appeared pertinent and could lend context to his photographs.

But Taylor did not confine his work to taking photographs, writing captions, and producing informed commentary. He also recognized the value of photographic research and the ways that photographs could be used as evidence and historical documents. This understanding could not have come at a more opportune moment.

Fed up with the low pay, cotton pickers in the San Joaquin Valley began walking out of the fields on October 4, 1933, under the banner of the Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union. One day later, 12,000 field hands were on strike. After growers began evicting strikers from their labor camps, pickers took over vacant lots and erected strike camps. The largest of these camps, dubbed “Little Mexico City,” held about 3,000 strikers and sprawled across four acres of Tulare Lake land near Corcoran. At first these developments drew little photographic coverage. But as strike leaders were arrested in the hundreds on vagrancy charges and sheriff’s deputies began seizing truckloads of food bound for the strike camps, tensions rose and dozens of photographers from around the country descended on the cotton district.

Among the most important photographs from the strike was one of a murdered farmworker. Taken by NEA photographer Fred Smith 20 miles east of Corcoran in the Tulare County town of Pixley on October 10, the horrible image shows a striker Dolores Hernandez, lying on a street in a pool of blood, attempting to prop herself up.

Taylor visited the San Joaquin Valley a week into the strike. He was accompanied by Clark Kerr, a new research assistant who had just arrived at Berkeley from Stanford University. They began amassing nearly two thousand pages of oral interviews, various fliers, documents, and newspaper clippings for a massive documentary history of the cotton strike. As they went about their business Taylor and Kerr also acquired photographs of strike meetings, strike camps, picketing, and the mortally wounded Hernandez.

Among Taylor’s most important acquisitions was the work of Ralph H. Powell. A 17-year-old high school student whose father operated a photo studio in Hanford, Powell spent several weeks documenting all aspects of the strike. But Taylor did more than collect images. Essentially a historian of the contemporary, Taylor incorporated one set of Powell’s images into the documentary history of the cotton strike that he was compiling. He then deposited a second set in the Library of Congress, and a third in the Bancroft Library, where they would be consulted and used by countless historians (without proper attribution or payment) over the next three-quarters of a century.

With eight years of photography and photographic documentation under his belt, Taylor was well on his way to forging a new phase in his career when, in the late summer of 1934, he first saw Dorothea Lange’s street photography on exhibit at Willard Van Dyke’s Oakland studio.

Taylor was awestruck by the powerful portraits of defeated men cast huddling around fires, resting on benches, and gathering outside soup kitchens. Not only were Lange’s images interesting and beautiful, they were valuable as empathetic documents of the times.

The two had contrasting personalities and contrasting skills—Lange, the artist, forever in motion, constantly talking, quick to react; Taylor, the academic, quiet, professorial, emotionally mature, strong and clear.

Lange’s talent was so great, and fit so perfectly with what Taylor had been trying to achieve, that he folded up his photographic work and handed it off. Lange absorbed Taylor’s interviewing techniques, shared his values and interests, and absorbed his scholarship.

Each divorced their current spouse and late in 1935, they married. They spent the next five years crisscrossing the United States and the California hinterland on an intellectual and visual odyssey that is without parallel in American history.