Coming up this weekend: an unusual 3-hour stroll through Cal’s 147-year history. But you’d better whistle while you walk, because it’s a walk through a graveyard—namely, Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland. On Saturday it will present its annual “Founders and Faculty of UC Berkeley” tour, led by docents Jane Leroe and Ron Bachman. Both are dedicated taphophiles—lovers of old cemeteries—and loyal Old Blues. (He got his bachelor’s from UC Berkeley in 1959; she got her hers in 1968 and her J.D. in 1971.)

Mountain View is the final resting place for a number of notable professors, regents and famous alums, including the first student to steal the Stanford axe, the capitalist who presided over the Northern Pacific Railroad, the muckraker who savaged the Southern Pacific Railroad, and famed but unassuming architect Julia Morgan, designer of Hearst Castle, who simply said “I want to be quietly tucked away with my own.”

The cemetery was founded in 1863, while the Civil War was raging in the rest of the country, when a group of prominent Oakland leaders met at the home of Dr. Samuel Merritt (buried in Plot 35) over brandy and cigars and formed the non-profit Mountain View Cemetery Association. “They had great concerns about being buried in the two decrepit old cemeteries that already existed—one where the Lake Merritt BART station is now located and the other between 17th and 18th Streets,” says Bachman. “After the College of California, which was founded by Henry Durant, morphed into the University of California six years later, Mountain View became the designated resting ground for Cal’s founders, faculty, and famous graduates.”

Among them:

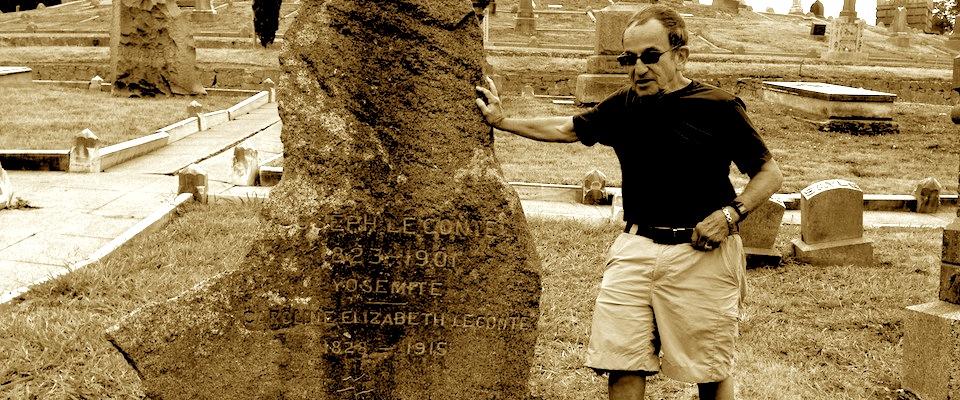

• John LeConte (1818-1891), Plot 6, who became acting president when the University of California was founded in 1868 and returned as president from 1876 to 1881, and his brother, Joseph LeConte (1823-1901), Plot 8.

The LeConte brothers, who grew up in Georgia, were professors of science at the University of South Carolina who offered their expertise to the Confederacy during the Civil War, supervising the production of gunpowder for the Confederate army. That made them virtually unemployable after Appomattox, so they joined the exodus of Southern intellectuals who came west looking for work, providing a handy talent pool for the new College of California.

“They came here in 1864 after their plantation was destroyed by Union forces in Sherman’s march through Georgia,” says Bachman. “John was the first professor hired, teaching physics, and Joseph was the third, teaching geology and botany.”

In 1870 Joseph made the first of many trips on horseback to Yosemite—a two-week, 250-mile journey each way—where he met the man who became his closest friend, John Muir. Together, they founded the Sierra Club two years later.

“He traveled to Yosemite on horseback every year after that and died there,” says Bachman. “His large granite monument was brought from Glacier Point to Mountain View, where he’s buried in Plot 6. John, by contrast, is buried in an unmarked grave in Plot 8.”

• Everett Brown (1876-1909, class of 1898), Plot 35, the first Cal student to steal the Stanford Axe.

The tradition of stealing The Axe is almost as old as The Axe itself, which made one of its first appearances on April 18, 1898, at a Cal-Stanford baseball game in San Francisco. The Stanford yell leaders paraded it around the diamond and used it to chop up blue and gold ribbons after every good play the Indians—as the team was then nicknamed—made.

Suddenly, Brown, a Cal senior, seized the Axe and ran off with it. He passed it to one of his Chi Phi fraternity brothers, who passed it to another, and then another, resulting in a furious chase through the streets of San Francisco, with Stanford students and the San Francisco police in hot pursuit. During the chase, the Axe’s handle was broken off.

“Another Chi Phi, Clint Miller, who was wearing an overcoat so he could conceal the Axe, was the last to handle it,” says Bachman. “As he reached the Ferry Building, he noticed the police inspecting the pockets of every boarding male passenger. Luckily, he ran into an old girlfriend. Posing as a couple, they boarded the ferry to Oakland to avoid the police, who were searching everyone buying tickets to Berkeley. From Oakland, Miller took the Axe back to Berkeley, where it was hidden in the Chi Phi house.”

As for Brown, he graduated two months later, attended Hastings Law School, and ended up on the bench as an Alameda County Superior Court judge, where, ironically, he earned a reputation as a no-nonsense, law-and-order jurist.

• Frank Norris (1870-1902, class of 1894), Plot 12, muckraking novelist whose classic, “The Octopus,” lambasted the all-powerful Southern Pacific Railroad.

“His fraternity, Phi Gamma Delta, paid for his gravestone, and they frequently come out here to honor him as the creator of the FiJi tradition of ‘kissing the snout of the pig’ at their Christmas dinners,” says Bachman. “They always leave a bottle containing yellow-tinged liquid on the grave, but we don’t recommend anyone drinking it. It’s probably not what was originally in the bottle.”

• Architects Bernard Maybeck (1862-1957), Plot 51, and his most famous student, Julia Morgan (1872-1957, class of 1894), Plot 33.

Maybeck began as a woodcarver, which influenced all his later works, but switched his interest to architecture and was trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He joined the Cal faculty in 1892, but since there was no School of Architecture at the time, he taught drawing in the Civil Engineering Department. He left his mark on the campus with the Hearst Mining Building, Hearst Hall, and the Faculty Club. He also designed a building for Phoebe Apperson Hearst’s home in Piedmont, which she used for entertaining. Later, she donated the building to the University, and it was moved to the corner of Bancroft and Bowditch to become the Hearst Women’s Gymnasium.

Maybeck also built the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition, the California Building for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, and his masterpiece, the First Church of Christ, Scientist, at the corner of Dwight and Bowditch, one of only two National Landmarks—the highest honor that can be given a structure or site in the United States—in Berkeley. (The other is Room 397 in Gilman Hall, a nondescript attic where, on Feb. 23, 1941, Glenn Seaborg and his colleagues first identified plutonium.)

Maybeck’s trademark was building in wood, which is why there are so few Maybecks left today. Many burned in the great Berkeley fire of 1923, and many more in the Oakland hills firestorm in 1991.

Not so with his prize pupil, Julia Morgan, whose specialty was building in stone. Most of her buildings still survive, including the Hearst Mining Building, Greek Theater, Berkeley City Club, Chapel of the Chimes in North Oakland, the Bell Tower at Mills College, and Hearst Castle at San Simeon.

The first woman admitted to Cal’s School of Engineering and the first woman admitted to Paris’s Ecole des Beaux Arts, Morgan also supervised the rebuilding of the Fairmont Hotel after the disastrous San Francisco earthquake and fire in 1906. And when Maybeck’s Phoebe Hearst Woman’s Gymnasium burned down in 1927, Morgan was given the commission to rebuild it, with funds from Hearst’s son, William Randolph Hearst.

Following her wish to be “quietly tucked away with my own,” Morgan was buried at Mountain View in 1957, the same year as her mentor—both with simple, unassuming grave markers.

• Francis Marion “Borax” Smith (1861-1931), Plot 35 – the Borax Smith Mausoleum.

This one’s a classic rags-to-riches story: One day a poor woodcutter cutting timber for the silver mines in Nevada; the next day a millionaire, thanks to stumbling upon a rich supply of something more valuable than silver: ulexite, the main ingredient in borax, a popular household cleaning agent and disinfectant.

He founded the Pacific Coast Borax Company in 1880 and made his 20-mule team famous for transporting borax across the Mojave Desert to the railroad line. He went on to fund the Bell Tower at Mills and found the Key System of electric streetcars and trains that linked San Francisco and Oakland before the advent of BART. But he’s probably most remembered today for something that happened 30 years after he died: a television show sponsored by 20 Mule Team Borax in the late and early ’60s called “Death Valley Days,” which hired an out-of-work actor named Ronald Reagan as host and launched him on a new career.

• Jane Krom Sather (1824-1911), Plot 35, who funded two landmarks on the Cal campus: Sather Gate, in memory of her husband Peder, and the Jane K. Sather Tower (aka The Campanile) which was built in her memory.

“She gave all her money to the University, which provided her with a generous income—a charitable remainder trust—in return,” says Bachman. “There were nude panels on Sather Gate that were initially removed but later replaced. The carillon in the tower is played every weekday in the morning, noon, and late afternoon except during finals. On the last day before finals the song is always ‘They’re Hanging Danny Dever In The Morning.'”

She is buried in the Borax Smith Mausoleum, since the two were good friends.

• Anna Head (1857-1932), Plot 6, one of the first women to attend Cal (class of 1879) and founder of the Head-Royce School in Oakland, one of the first college prep schools to admit females.

“In 1888 she started a school in Berkeley called Miss Head’s Preparatory School for Girls, offering academic subjects, physical education, cooking, music and art,” says Bachman. “She later sold the school, which moved to the Oakland hills, began admitting boys as well as girls, and changed its name to Head-Royce in honor of philosopher Josiah Royce (class of 1875), who married Anna’s sister Katherine.”

Head was fond of snakes and enjoyed bringing them to school, to the dismay of many of her students. But despite her enthusiasm for coeducation, she was adamantly opposed to women’s suffrage, also to the dismay of many of her students.

By contrast, her classmate at Cal, Mary McHenry Keith (1855-1947, class of 1879), Plot 14B, was an ardent suffragist and a close friend of Susan B. Anthony. The first female graduate of the Hastings School of Law, she practiced law until her marriage to the eminent landscape painter William Keith (1838-1911), who is buried next to her in Plot 14B. After his death she devoted the rest of her life to women’s rights.

• Samuel Merritt (1822-1890), Plot 35, physician, philanthropist, Mayor of Oakland, founder of Merritt Hospital, and one of the founding Regents of the University.

“He arrived by ship in San Francisco in 1850, shortly after a devastating fire destroyed the city,” says Bachman. “Fortunately for him, his cargo included nails and other building materials that he sold for a great profit. It became the basis of his fortune, which he expanded in business and real estate, buying land along what would become Lake Merritt and subdividing it for elegant homes. It was his decision to dam the lake and construct floodgates to control the level of tidal flow. The City of Oakland paid $20,000, and he paid the rest. At first it was named Lake Peralta, but everyone called it Merritt’s Lake, and eventually Lake Merritt.”

But his time on the Board of Regents was less enjoyable.

“He was appointed by the other Regents to build the first building on campus, North Hall,” Bachman says. “But the building cost $24,000 more than it was worth, and he was accused of profiteering. Because of this, he repaid a small part of the money and resigned from the Board of Regents.”

• Frederick Billings (1823-1890), another founding Regent, who has the distinction of naming not one but two different cities: Billings, Montana, a railroad town that, as president of the Northern Pacific Railroad, he named after himself (even though he never lived there), and Berkeley, California.

One day in May of 1866, Billings and the other Regents held a picnic at Founders Rock, an outcropping at the corner of Hearst Avenue and Gayley Road, where they talked about the most pressing issue of the day: What to name the town that was growing up around the new university?

Standing on the rock’s summit, Billings was so moved by the view of ships sailing through the Golden Gate, he was inspired to quote poetry: “Westward the course of empire takes its way.”

“Who wrote that?” someone asked.

“Why, George Berkeley, the Bishop of Cloyne,” replied Billings. “That’s it! Berkeley! We’ll name the town Berkeley!” And the rest is history.

So was Billings, who moved back East shortly later to assume the presidency of the railroad, never to return to Berkeley—or Billings, either. He died and was buried in Woodstock, New York, which makes him the only person featured on the tour who isn’t actually buried at Mountain View. But hey, a great story is too good to pass up.

• Henry Cogswell (1820-1900), Plot 7, the first dentist in San Francisco.

“His is the largest monument at Mountain View, 70 feet high and 329 tons,” says Bachman. “It took 38 freight cars to ship it to Mountain View from the East Coast.”

Cogswell came to San Francisco in 1849 via clipper ship around Cape Horn. “He sold goods to the miners and fixed their teeth, but he made his fortune as a land speculator,” Bachman says. “He donated money to UCSF for a dental school that he wanted named after him. They took the money but never made it the UCSF Cogswell Dental School.”

A lifelong temperance crusader, Cogswell believed that people wouldn’t drink alcohol if they had access to cool drinking water, so he built “temperance fountains” in cities throughout the country, including San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Washington DC.

“Many of the fountains featured a bronze statue of a man who looked a lot like him,” Bachman says.

San Francisco’s temperance fountain was torn down on the New Year’s Eve night of 1893-94 by a “lynch party of self-professed art lovers,” according to contemporary newspaper accounts. But the one in Washington D.C.—often called “the city’s ugliest statue”—is still there at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 7th Street, topped by a sculpture of a heron, meant to symbolize the superiority of water over alcoholic beverages.

Cogswell is honored every month at a banquet of the Cogswell Society in the nation’s capital. The master of ceremonies, called the “Lead Heron,” opens each meeting by standing on one leg, hoisting his glass, and offering this toast: “To temperance!”—to which the members respond by standing on one leg and shouting, “I’ll drink to that!”

Mountain View Cemetery is located at 5000 Piedmont Avenue in North Oakland. The Sept. 26 tour is free, and will begin at 10 a.m. and last approximately three hours. For more information, call 510-658-2588.