With former President Mohammed Morsi out and the Egyptian Army at least temporarily in, speculation is rife that it was all a set up, that the army whipped up the Egyptian Street by arranging bogus shortages of food and fuel so the top brass could seize the reins from Morsi’s power base, the Muslim Brotherhood.

In other words, the deposition of Morsi was an out-and-out coup, not a measured response to the President’s unpopular Islamist policies.

How much credence should we give this theory? We bruited that question about to Middle Eastern experts in Berkeley. One declined to comment, one was on vacation, and one didn’t get back to us. But Nezar Alsayyad, the chair for UC Berkeley’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies, took our call – and he had a lot to say.

First, Alsayyad dismissed the idea that the Army had somehow arranged the resource shortages that drove the protests against Morsi. The fact that abundant fuel was available shortly after the President was deposed is easily explained, he says: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates dispatched tankers once the Army established control.

“It only takes a day transit for oil to get from the Gulf nations to Egypt,” Alsayyad says. “It’s no surprise that they hadn’t been supporting Morsi (with fuel). They (the Gulf countries) have no sympathy for the Muslim Brotherhood, and it wasn’t in their interests to support them.”

But what about charges that the takeover was an arrant coup against a duly elected leader?

“First, I adamantly reject the term ‘coup,’ ” said Alsayyad, who gave a similarly impassioned interview to Aljazeera earlier today. “This was not the legal definition of a coup. The military is by no means in full charge of the country. Many of (Morsi’s) cabinet ministers remain in place. Does the Army control a significant part of the economy? Yes – about 20 percent. But that has been the case for a very long time. The Army has always had its own resources.”

Second, said Alsayyad, Morsi’s “legitimacy” is over-rated.

“People in the West may forget there were two elections, and in the second Morsi was in a run-off with Ahmed Shafik, the Prime Minister under Mubarak. The turn-out in this election was low, and Shafik was roundly hated by everyone – many of the votes for Morsi were protest votes against Shafik. And in the end, Morsi won by a margin of 51 percent to 49 percent. That is not a mandate.”

Furthermore, Alsayyad continued, “Hitler was ‘duly’ elected too. Obama told Morsi that democracies are more than elections – and he was right. Morsi forgot that it’s the Arab Street that confers legitimacy, not dubious elections.”

Alsayyad says he is sometimes frustrated by the western media’s tendency to create “false dualities.” Contrary to some reports, he maintains, Egypt is not evenly divided between Islamist and secular factions; the two sides shouldn’t be given equal weight.

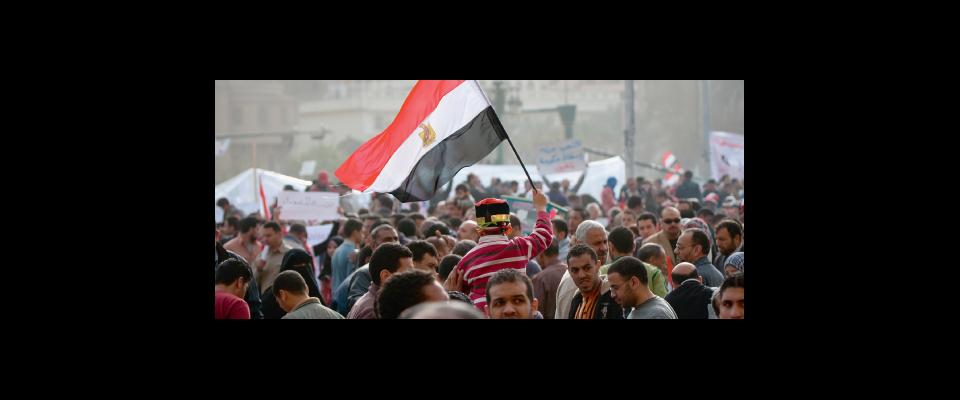

“The demonstrations in support of Morsi are restricted to two small squares in Cairo,” he said. “There aren’t any to speak of in any other part of Egypt. Meanwhile (during the height of the protests against Morsi), no fewer than 15 million people were demonstrating in Cairo alone. It is very clear who is in the majority, and what they want – they reject the whole notion of a theocratic state.”

— Glen Martin