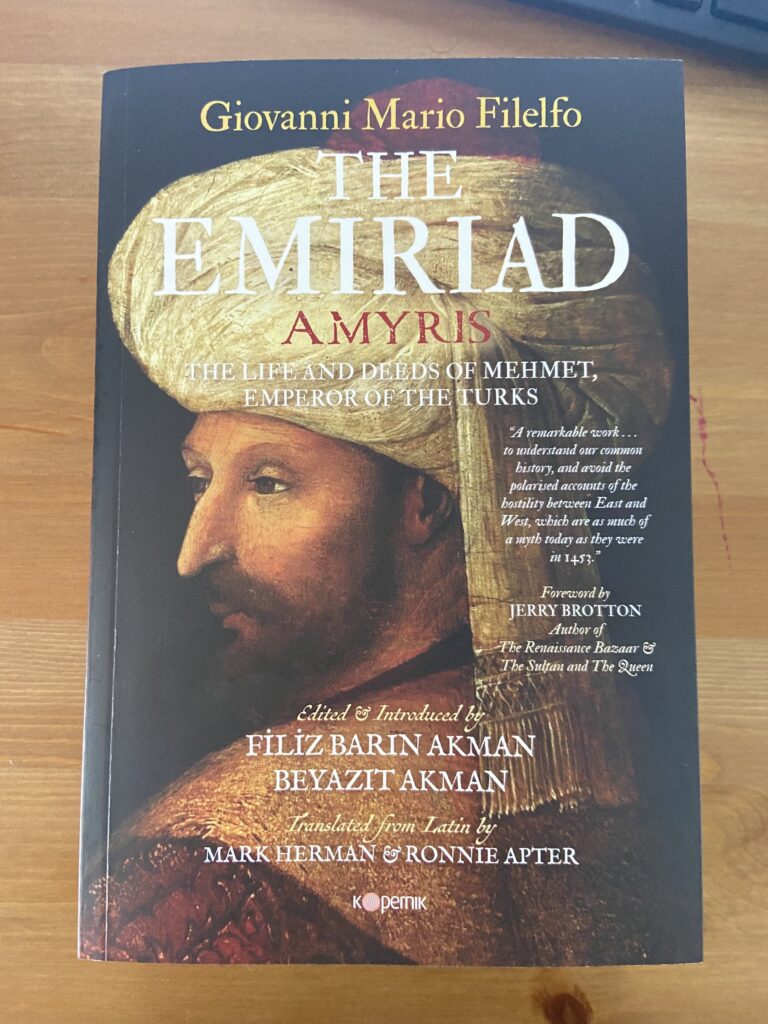

Mark Herman (’65 MS), together with Ronnie Apter (Professor Emerita of English at Central Michigan University), has translated for the first time into English Amyris, de vita et gestis Mahometi Turcorum imperatoris / The Emiriad: The Life and Deeds of Mehmet, Emperor of the Turks, a Renaissance epic poem (1471-76) in Latin about the Turkish Sultan who conquered Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1453, thereby ending the Byzantine Empire. Amyris, consisting of some 5,000 lines grouped into a short Introduction and four books, is by Mehmet’s contemporary, the Renaissance Italian poet Giovanni Mario Filelfo (1426-80). A simultaneous Turkish translation, Emir, has been made by Ahmet Deniz Altunbas. Two Turkish professors at Ankara Social Sciences University, Filiz Barin Akman and Beyazit Akman, commissioned the translations and have written an extensive introductory analysis. The work, with a Foreword by Jerry Brotton of Queen Mary University of London, is published by Istanbul-based Kopernik Kitap, and was supported by the Turkish Culture and Tourism Ministry.

Amyris was commissioned by the Renaissance Italian merchant Othman Lillo Ferducci, whose father was a close friend of Murat II, the father of Mehmet II. The idea of an epic honoring Mehmet arose when Mehmet, without demanding any ransom, released Ferducci’s brother-in-law, who was among the prisoners captured during the 1453 conquest. Due to the Turkish-Venetian Wars, Amyris could not be taken to Istanbul and was never presented to Mehmet II. A single manuscript copy remained in Europe, eventually coming to the Geneva, Switzerland, Library where it still is, a work virtually unknown for over half a millennium, though a transcription was published in Italy in 1978.

To quote from Jerry Brotton’s Foreword:

[Amyris] is more than just an encomium praising Mehmet in the style of Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid: it is a valuable document of a moment when the Latin western tradition worked closely with the Islamic eastern world to produce a new kind of text based on competition over a shared intellectual heritage that both cultures acknowledged . . . . [Amyris] should alert us . . . [who work] between east and west, Greek and Latin, Turkish and Arabic, to be aware of how scholars today need to work collaboratively and to pool their highly specialised skills . . . if we are to understand our common history, and avoid the polarised accounts of the hostility between east and west, which are as much of a myth today as they were in 1453.