When Rebecca Skloot was 16 years old, her biology teacher wrote a name on the blackboard: “Henrietta Lacks.” He explained that Lacks was a black woman whose surgeon had extracted cells from her tumor in 1951. They turned out to be the first human cells to survive indefinitely in a laboratory. Billions of so-called HeLa cells lived in labs around the world and had helped produce treatments for leukemia, influenza, Parkinson’s disease, and many other ailments.

That lesson changed the course of Skloot’s life. She spent a decade unearthing the lives of Henrietta Lacks and her descendants, as well as the ethical fallout of her non-consensual contribution to science. Skloot’s 2010 book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, remained on the New York Times paperback nonfiction bestseller list for 75 weeks. A film version of the story starring Oprah Winfrey premiered on HBO late last month. Skloot, who was recently a lecturer at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, appeared as a character in the movie, played by Rose Byrne.

I spoke to Skloot about telling Lacks’ story and what it was like to see her words—and herself—come to life on the screen. Her responses have been edited for clarity and length.

How involved were you in the process of adapting your book into a movie, and what was your vision for it?

I was probably more involved than most writers are. It’s such a complicated story, and I felt it was important for me and the Lacks family to be involved as contributors. I didn’t want the movie to over-fictionalize things. Five members of the Lacks family read the script before filming started and gave feedback, and I went through it with the screenwriter as well. I wanted to bring Henrietta to life, I wanted the science to be portrayed clearly, and I wanted the character of Deborah [Henrietta’s daughter] to be accurate.

Of course, I had 400 pages to tell the story; in a 90-minute movie, many things inevitably get left out. But there are things movies do that book’s can’t. The emotional impact of seeing the story brought to life with real people was powerful. There are some scenes with Henrietta dancing where you really see her as a person. What you can do in a movie in a minute would in some cases take many pages in a book.

What was it like to see yourself portrayed as a character in the film?

It’s really surreal. Rose did an amazing job of bringing the physicality of me to life in a way that’s really haunting. There’s a moment where she’s up on a ladder pulling a box of research materials off a shelf, and my dad gasped, “It’s like I just saw a home video of you 20 years ago.” It was incredible to watch the work that Rose put into it, because Rebecca in the movie is still a bit one-dimensional — we don’t learn about what’s going on in her life outside this process. Rose and I locked ourselves in a hotel room for several days and talked about my life and background so she could internalize it and act from that place, even though none of that’s in the movie. It’s really impossible to convey journalism accurately in a film, because it would be a really boring movie: years of phone calls and me sitting in basements looking through piles of papers.

Tell me about working with Oprah.

It was amazing to watch her dive into the character as Oprah the actor as opposed to Oprah the talkshow host or Oprah the public figure. She spent a lot of time talking with the family and dove into the tapes I’d made of my time with Deborah [who died in 2009]. On one of those tapes from around 2001, we’re driving to get dinner, and Deborah says, “You’re going to finish the book, it’s going to become a bestseller, and Oprah’s going to play me in a movie.” I was a grad student then with no book contract. I said, “That would be amazing, but I just hope I can find a publisher.” It was a relief that Oprah was involved and handled Deborah with respect. She’s a very complicated character, and it would’ve been to easy to portray her as erratic and emotional.

How did the Lacks family receive the film?

Five family members were formally consultants on the movie, and many others were involved. Dozens visited the set at different times. For me, the most incredible part of the process was watching the family be ecstatic about the movie in the end because so many people were watching and appreciating it. One or two family members [Henrietta’s son Lawrence Lacks, and his son Ron Lacks] who had not seen the movie got a publicist involved, and several stories came out. But the vast majority of the family was incredibly positive, and these folks were not involved by choice. In the end, one of them came to the premieres and was celebrating with the rest of the family.

A group of six or seven family members are now traveling around the country, sharing their story with students and scientists and consulting on how to bring people into the research process. The story didn’t stop with Henrietta: Her children were used in research without their consent in the 1970s, and later the HeLa genome was sequenced and put online without the family’s consent. This generation said, “It stops with us, and we want to be part of the process now.”

What are you working on now?

When I finished my first book, I thought, I have to do something totally different because nothing can possibly compare. The irony is that I’m working on something very similar. I think writers do this: We have core stories we tell over and over again. The stories I get obsessed with have to do with the gray areas where science and everyday life meet, that are ethically complicated and people don’t like to think about.

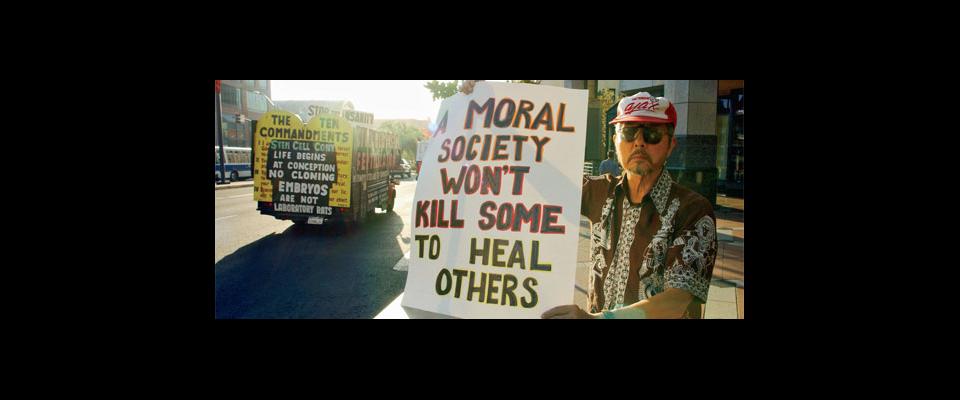

Like HeLa cells, everyone benefits from animal research on a daily basis, but no one likes to think about it. I’m interested in where you draw the line between the value of science and the impact it has on the research subject, whether animal or human. Before I became a writer, I wanted to be a vet and worked as a nurse for animals. When I took my first writing class, the first story I wrote was about the morgue in the vet school. I thought, do people know how many animals come into this freezer every day, and what’s actually coming out of this research?

My second book is going back to those animals: looking at whether anybody benefited from that, what role animals play in our lives, and the ethics of it all. I’ve been working on it for a lot of the last six years, and I hope to finish the rest this year. I’ve been working on and talking about Henrietta Lacks for about 18 years now. I’m ready to be the person who’s doing the new thing.