Are We Born Racist? When that question became the provocative title of a 2012 book by psychology professor Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton and his team at UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, the science seemed to answer that question in the affirmative. Children as young as five months show a preference for people the same race as themselves.

Further research, however, suggests that isn’t the whole story.

It’s true that we are born wanting to sort people into categories; it’s part of what helps us function socially. But those categories are not only learned, they continue to shift depending on circumstances. For example, a red shirt at a holiday party wouldn’t cause a stir, but the same shirt at a Cal football game certainly would. Part of what those babies are picking up on are cues about what’s important in their social group, whether it’s skin color or shirt color.

Perhaps equally provocative is the finding that trying to be “color-blind” can actually damage your social interactions. Because Americans are conditioned to recognize race as a social category, not noticing means suppressing any reaction—which gives the person you’re interacting with an uncomfortably flat impression from you. As Mendoza-Denton puts it, “in order to avoid any bad reaction, you’re throwing any positive reaction under the bus with it.”

So what can we do? The answer is charmingly simple: Get to know other kinds of people. It turns out that positive interactions with even one member of another group carry over to your reactions to the whole group.

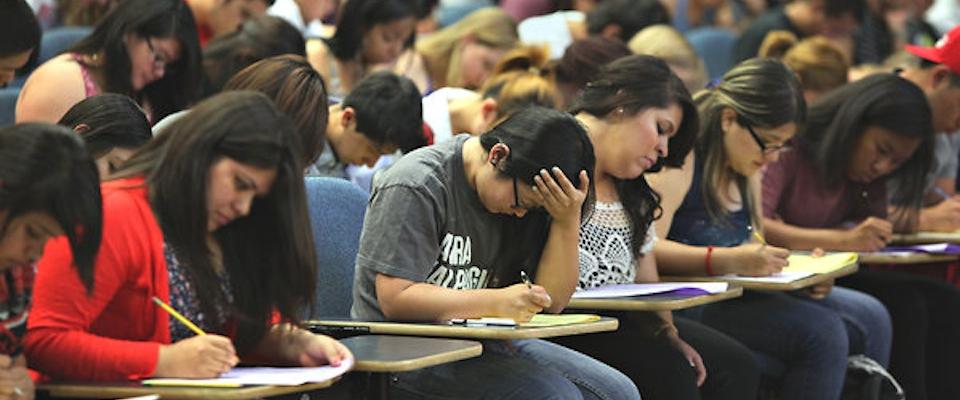

Meanwhile, the Greater Good Center is combining those findings with research on empathy and understanding to find usable strategies for interracial relations, especially for institutions. One example Mendoza-Denton cited: minority students in science, technology, engineering and math disciplines are most likely to have a non-minority advisor, so improving cross-cultural communications could have a positive affect on student retention and graduation.