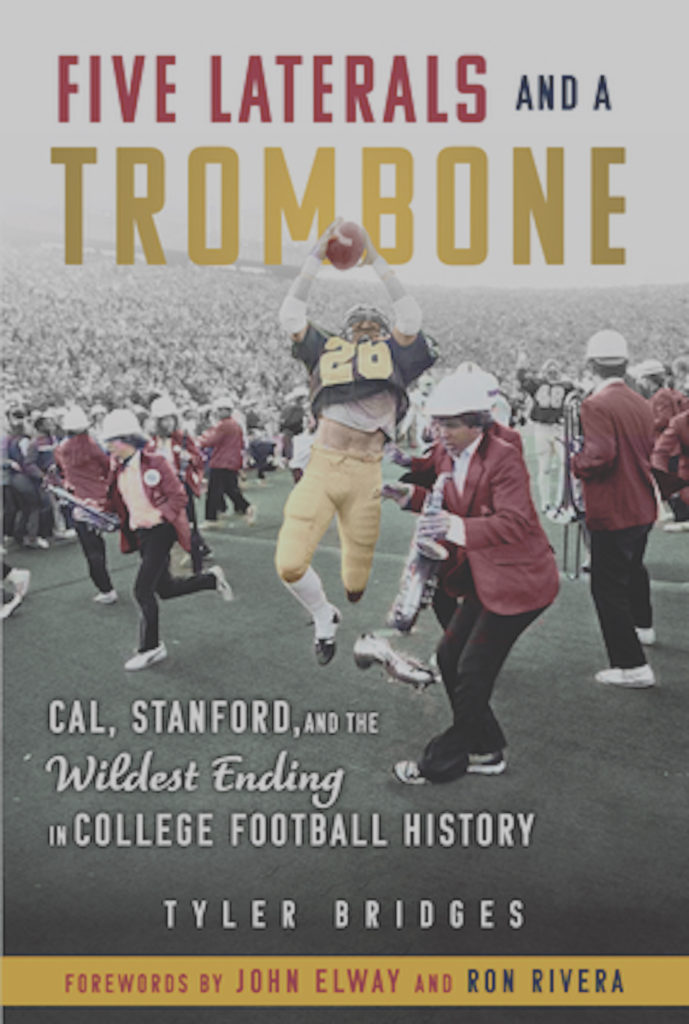

This Saturday, in California Memorial Stadium, the California Golden Bears and the Stanford Cardinal will square off for the 125th Big Game. It also marks the 40th anniversary of The Play, the greatest and unlikeliest finish of any college football game in history. In a newly published and exhaustively researched book, Five Laterals and a Trombone, veteran news reporter and former Stanford trombonist Tyler Bridges puts readers back into the action, providing unmatched context and insight on that moment in 1982 when the football gods proved to fans everywhere that the cliches really are true: Anything can happen, and It ain’t over till it’s over.

California caught up with Bridges earlier in the week. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Where were you when The Play transpired?

The Play took place on November 20, 1982. I was in Washington, D.C., then. And there was a radio hookup to the game for Stanford and Cal alums, which was an amazing thing at that time, to be in Washington and be able to listen to a game on the radio in the Bay Area. It was at a boathouse in Georgetown. And so I was there with a bunch of Stanford buddies. I don’t remember very much about the game except the end when Mark Harmon kicked that “winning” field goal. My buddies and I did a ‘Give ‘em the Axe’ yell and then went off and partied. I didn’t know ’til the next day, when I picked up the Washington Post, that Stanford had actually lost the game on this incredible ending.

Having been a recent alumnus of both Stanford and the Stanford band, were you immediately in touch with old friends who were there?

Yeah, I was. Gary Tyrrell and I had played trombone together in the band. He always carried a bottle of Jameson Whiskey with him and I wondered whether, when he got hit, the bottle was smashed? He told me he had already finished it and tossed it before he and Kevin Moen met in the end zone.

That’s a great detail. So, what convinced you to revisit the story 40 years later?

This is a very California story. I went skiing in Tahoe in 2016 with my daughter, Luciana, who was 14 at the time. So after the day of skiing, we get into the outdoor jacuzzi, and in gets another family and I started talking to the father, Kris Van Giesen, a Cal alum. He learns I’m a Stanford guy and immediately starts making fun of me about the 1982 Big Game. He says to me in this whiny voice, “John Elway says it ruined his last game at Stanford.” And so I said, “Yeah, but you know, you guys haven’t been back to the Rose Bowl since 1959.” And we go back and forth like that, but end up laughing and shaking hands. And in fact, we’re still in touch.

After, I took Luciana back to where we were staying and, because she had no idea what we were talking about, I showed her The Play. I got emotional when I watched it. I was on the verge of crying. And that was not the first time. Because I grew up in Palo Alto, going to Stanford football games with my dad, and then played in the Stanford band—it just felt like it was my story to tell.

Was it a hard book to pitch, given how much time has passed?

Well, I’ll tell you two things I’ve learned. The first is, it is still well known throughout the country, because ESPN shows it every year. And it’s such an iconic ending. It will never ever be repeated. When I mentioned that I’m doing a book on it, people might pause for a moment. And then they’ll say, “You mean, when the band was on the field?”

The other thing I’ll say is that the collective memory is much greater in Berkeley and among Cal grads than it is amongst Stanford fans. Part of that, I think, is because Stanford lost and they want to forget about it. But also, you know, unfortunately for Cal, they haven’t been back to the Rose Bowl since 1959, when Joe Kapp was quarterback. So there’s not a lot to cheer on in the recent history of Cal football. For Cal fans, The Play becomes kind of a lasting image of a great, glorious moment for the Golden Bears.

You’re a veteran reporter, but also a Stanford fan through and through. How did you maintain your objectivity for this project?

You’re right: I grew up in Palo Alto, my dad went to the law school on the GI Bill after the war. My mom was a secretary at Stanford. Now I have a daughter there. So yes, I’m Stanford through and through, but I approached it the same way I do when I cover politics. I’m the chief political reporter for Louisiana’s biggest newspaper. And there, I have to be able to talk to Democrats and Republicans, and I have to set aside my own political views, and try to be fair and objective and give everybody a voice. And sometimes I’ll write stories that Democrats won’t like, and sometimes I write stories that Republicans won’t like. And so I just approached it the same way. That’s why I interviewed so many people from both sides. I really just wanted to tell an entertaining story—the story behind the story of the craziest finish ever in college football history.

You really did interview a lot of people. And there are a lot of great characters in the book, including quarterback John Elway, and coaches Joe Kapp and Paul Wiggins. Who stands out for you as the most interesting or surprising character to emerge from your research?

One guy I really enjoyed tracking down was the guy that signaled the win for most people. Everybody who was there admits that when the game ended there was total confusion. Most of the people at Memorial Stadium didn’t know who had won. And they figured it out because of the cannon on Tightwad Hill. Everybody knew, when that cannon went off, that Cal had scored. So I made it my mission to find that guy, and tell it from his vantage point. That’s the level of detail I was searching for.

As you say, there were only four seconds on the clock when The Play started. How many pages do you think you devoted to those four seconds?

Well, Sports Illustrated published an account by a guy named Ron Fimrite—a Cal alum—in 1983. And that was the best version of The Play that was ever written. All the other stories were retrospective, and I didn’t want to tell a retrospective story, I wanted to make you feel like you needed to turn the page to find out what happens next. And Fimrite did that, in a much smaller version. So the goal was to take what he had done and expand it. I interviewed 21 of the 22 players who were on that field for the final kickoff. Only Mariet Ford didn’t respond to my letters to him in prison. And for that final Stanford drive, I interviewed everybody on the field, except one Stanford player who’s deceased and a Cal defensive back who didn’t get back to me. I just tried to get as many perspectives as possible, and then weave it all together in what I hoped would be a seamless narrative.

Okay, so the questions that are always going to be asked: Was Garner’s knee down? And was the last lateral forward or not? What do you say?

I go with what the officials say. I interviewed the five surviving officials and the two guys who had a clear view. One said it was inconclusive. He couldn’t tell, but he didn’t blow the whistle. And the other official said he was sure that Garner was not down. Now, there’s some good evidence to think that the final lateral was forward, but my feeling is that it’s settled history. I didn’t try to write the book to prove that Stanford actually won the game. Cal won the game, 25 to 20. I know Stanford friends of mine will disagree. It was a terrible loss for Stanford seniors and fans, but the reason we’re still talking about it is because of the way it turned out. And, you know, it speaks to the improbabilities of life, the importance of never giving up. You just never know, sometimes, where things might go.

Where do you expect things to go this Saturday at the 125th Big Game?

I won’t make a prediction. But I’ll tell you this. You know, when we play each other, Stanford and Cal, each side wants to beat the other. But we go off into the world after graduating and work with people from the other school and become friends. There’s a real camaraderie there and I think it’s epitomized by Kevin Moen and Gary Tyrrell who’ve become friends over the years. You know, they collided at that moment in the end zone 40 years ago, but now they’re good friends. They laugh about it. And I think that’s the way it should be.