On July 11, protests broke out simultaneously in various Cuban cities and towns, spurred on by the collapse of the healthcare system due to the pandemic and a severe economic crisis. The socialist government, headed since 2018 by Miguel Díaz-Canel—Raúl Castro’s handpicked successor—responded with police repression, the detention of hundreds of protesters, and by cutting off internet access across the island.

Since then, Cuban protesters have been given summary trials without legal representation and given lengthy prison sentences. The international community has largely been supportive of Cuban protesters, whose mantra is “Patria y Vida!” (homeland and life)—a dissenting appropriation of the Cuban socialist mantra “Patria o muerte,” homeland or death. Nonetheless, some leftists have blamed all of the island’s woes on the U.S. embargo, echoing Díaz-Canel’s rhetoric.

Elena Schneider is an Associate Professor of History at UC Berkeley whose research concerns comparative colonialism and slavery within the Black Atlantic. California spoke with Schneider about the significance of these historic protests and the polarized discourse about Cuba in the U.S.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you speak about the significance of the July 11 protests and whether they have precedents during the Revolutionary period [since 1959]?

I was moved by the bravery of so many people willing to take that risk, including older Cubans who’ve always been categorized as the stalwart supporters of the Revolution but who were in the mix with younger folks. When the people of San Antonio de Los Baños took to the streets, the news spread on social media; the logic was, they can’t stop all of us if we go at once, so people jumped at the opportunity.

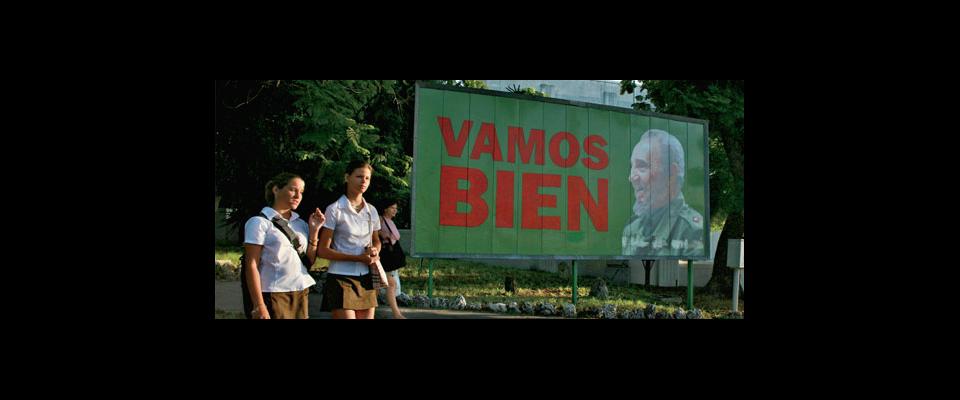

The precedent people have pointed to is the Maleconazo in 1994, when Cubans hijacked the Regla ferry to try to get off the island during the extreme scarcity conditions of the Special Period [the economic crisis in the early to mid-1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s primary benefactor]. The same tactic was implemented then, where government counter protests were organized immediately. Fidel got people to stop protesting when he told them, “If you want to leave, you can leave.” And that provoked the rafters crisis [thousands of refugees fled Cuba on homemade rafts], which was a human rights tragedy. However, there was still a lot of respect for Fidel Castro on the island and he was able to capture the moment and redirect it.

But the number of people and the extent of protest on July 11 was of greater scope. I’ve never seen anything like the outright hatred and disrespect for Miguel Díaz-Canel—going back to [dictator Fulgencio] Batista. This government’s strategy has been to muzzle artists, limit use of social media, control public performances, and to increase imprisoning of dissidents even before July 11. The strategy has been an aggressive curbing of criticism just as Cubans got a new leader who they are not fans of.

Even before the protests, I felt Cubans wouldn’t make endless sacrifices for the country, which Fidel often asked of them. There’s no loyalty to Díaz-Canel like there was to Fidel.

He’s not even a Castro—he’s a bureaucrat who positioned himself well enough to not threaten the status quo. There’s also been a big generational change in Cuba in the last 30 years since the Maleconazo, and a tremendous amount of suffering. The positives [of the Revolution] are being increasingly overshadowed by the daily privations, struggle, and bureaucratic doublespeak.

We’ve also seen increased privatization measures that began under Raúl, and the growth and power of the Revolutionary Armed Forces. It controls more of the money that comes in through the tourist sector. So there’s been less of a feeling of fiery solidarity with the people—the government has created a privileged bureaucratic class that’s not dealing with the daily struggles to find food and Tylenol that Cubans are going through. One of the prime examples is the efforts to correct the currency over this past year. Can you think of worse timing for causing extreme duress to the Cuban people?

It was entirely predictable if you do that [when tourism is down 70 to 80 percent]. The GDP dropped 11 percent last year and another 2 percent this year. Then there’s the problem of where to get foreign aid during Venezuela’s implosion, and Cuba’s COVID uptick over the summer. They had one of the best responses in Latin America in containing the virus initially, but then they decided to reintroduce tourism. We’re always dealing with this problem of how do we verify anything when the Cuban government controls information? This is coming up with COVID case count issues—a local administrator in Guantanamo recently gave much higher numbers of deaths per day than the official state figures.

What are other factors that contributed to widespread protest now?

The apagones (the massive power outages), the general economic free fall of this moment. The embargo is always a factor, but especially the tightened Trump sanctions of cutting off remittances [from Cubans abroad]—they have caused a lot of suffering for Cubans. It’s ironic that you can credit this protest in part to Trump’s inhumane sanctions, in part to the embargo, but also in part to Obama’s visit [in 2016] and the pressure he put on the government to allow for more internet access.

As Cubans will remind you over and over again, they’re not on the streets shouting “down with the embargo!” They’re shouting, “Patria y vida!,” “libertad!” [freedom], and “Díaz-Canel singao!” [Diaz-Canel motherfucker]. They’re saying, “This is not about the embargo. Listen to us.” They are so tired of a broken rhetoric of hardened positions on the left and right—both the Marco Rubio or “invade” school and the hard left, where you’re not allowed to criticize anything about Cuba and everything is because of the embargo. To have many Americans immediately blame the embargo is so tone-deaf because that’s exactly what Díaz-Canel did to justify detentions of hundreds of journalists and ordinary Cubans and the murder of a protestor. It was painful to see how little people were paying attention to the San Isidro Movement and the arbitrary detentions of Cuban artists, rappers, and dissidents that had been ongoing, which was a crucial antecedent for this protest.

The embargo can only be overturned by both houses of Congress. There’s no way that’s happening right now. Biden made a campaign promise to loosen Trump’s restrictions, and now hasn’t because of July 11, which is further exacerbating Cubans’ suffering. Our broken politics around Cuba aren’t helpful.

There is also a prioritization of international politics and posturing in the way COVID has been handled. The Cuban government developed three vaccines, and Cuban doctors went to Italy to help during the peak of COVID outbreaks. But they’ve also allowed the domestic health system to fall into neglect over the last decade. And it’s a tiered system. There’s the kind of care the bureaucratic privileged class gets, that Gabriel García Márquez and Hugo Chavez got, which is a whole different class of medical care than ordinary Cubans get. Americans still have this outdated myth of the extraordinary medical care available for free to ordinary Cubans.

Cuba also sends doctors to other countries as a way of generating income. There’s a contingent of doctors that does humanitarian aid for free, but those aren’t the doctors who spend years in Venezuela. And doctors are only paid a small percentage of what these countries are paying Cuba.

The fact that the government remade the medical system, after between 40 and 50 percent of Cuban doctors left after the Revolution, was an amazing feat. For a long time there were tremendous medical gains for ordinary Cubans. But I know a doctor who tried to leave on a balsa [raft] and was imprisoned for that, I know doctors that defect. There was a State Department program to try and induce them to do that, but it wouldn’t have been in place if doctors hadn’t been willing—the U.S. saw a weakness there. It was stunning to watch doctors in Holguín publicly criticize the prime minister, who blamed the collapse of the medical system on them.

It was very brave of them to post videos on social media showing the actual conditions in Holguín and expressing their anger that when government functionaries come to visit, they don’t talk to the doctors about what they need, and the fact that they aren’t able to do chest x-rays and don’t have enough oxygen. We’ve seen doctors protesting their government’s failure to respond quickly all around the world, but the stakes of doing so in Cuba are high.

How did the expansion of the internet in recent years help make these protests possible?

News has always spread via “Radio Bemba” [“lip radio” or gossip] in Cuba. Social media allowed that to happen at greater volume across the island. But it’s also things like “el paquete” [weekly package of media content smuggled in from the U.S.] and a tighter interweaving of Cuba with news from the outside. Cubans used to ask me to bring the most recent copy of the New York Times, but now people are more connected, they’re getting information from el paquete. They’re having regular conversations with relatives in the diaspora. When Obama gave that famous speech in the Teatro Alicia Alonso, his speech to the Cuban people, that was not broadcast on state media. Most Cubans came across it because it was passed around through el paquete.

Trump exacerbating the agony of the Cuban people contributed to the perfect storm. But it’s also very important to look at what Cubans have said. They’re protesting the actions of their government, which make conditions worse. Especially in Guantanamo or Holguín where the public health system seems to be in an extreme condition of collapse, they’re yelling about Díaz-Canel. Since 1898, Cuba has always labored under the problem of American imperialism, but what has people so enraged right now is a government that exacerbates their suffering and seems to not feel any solidarity with them.

How do you feel about the Biden administration’s response thus far?

I’ve been disheartened by Biden’s willingness to prioritize electoral politics in Florida over the right thing to do and his own campaign promise. He’s an inside Washington guy, and he sees Cuba as a horse to be traded. I was disappointed by his lack of willingness to take a stronger stand on getting humanitarian aid to Cuba—he has only allowed limited humanitarian charter flights into Havana.

Judging from the reaction on social media, many Cubans in the diaspora were convinced the July 11 protests were a turning point in terms of the fall of the socialist regime. What do you foresee may happen in the next year or two?

I’ll give you the historian’s response: July 11 is a moment that tracks back to the San Isidro Movement protests, and back to the Maleconazo and the 1980 Mariel crisis. It’s part of the story of Cuban people gaining political voice and taking control of their government in whatever form it may take. My hope is that it’s a sign of a civil society that cannot be silenced anymore by the government, and that Cuban people get to have a say in the transition. My fear is some kind of tumultuous transition with loss of life and economic suffering for ordinary Cubans.

Since Raúl’s presidency, this government has been largely unfeeling toward the struggles of ordinary Cubans. There’s much more social inequality on the island and people aren’t willing to take it anymore. So my hope is that they’re able to gain control of their own government to protect their lives better and to aid them as they struggle against the precarity of their living conditions.

Image credit: “2021 Cuban government protest in Naples Florida” by P,TO 19104 licensed under CC.BY 4.0