A California crown for Lord Byron.

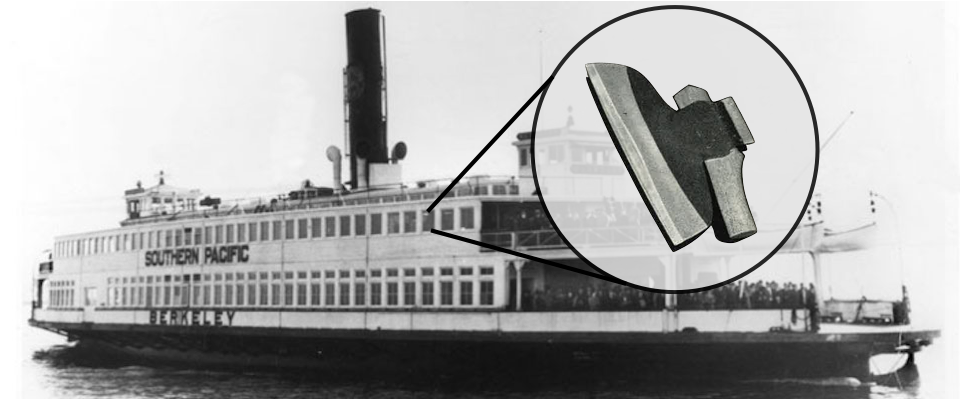

One late July day in 1870, two poets boarded a side-wheel ferry at Meiggs Wharf in San Francisco. The Princess plowed six miles across the mouth of the bay to what was then the village of “Saucelito,” at that time just a few piers and a building or two at water’s edge. The ferry usually carried prospective buyers for the residential lots that had recently been carved out on paper, but the poets hadn’t come to look at real estate. They were on a mission to defend the memory of Lord Byron.

When the ferryboat arrived, Ina Coolbrith and Cincinnatus Hiner Miller walked ashore and climbed the steep chaparral hillside. He was tall, blonde, and blue-eyed and had arrived in San Francisco from Oregon earlier that month wearing beaded moccasins, a sombrero, and a white, ankle-length duster. The flamboyant outfit had been noted with appreciation by Charles Warren Stoddard, a San Francisco poet who had agreed to show Miller around town. As it happened, Stoddard was scheduled to leave for Tahiti the day after Miller’s arrival and so asked fellow poet Ina Coolbrith to step in as literary host. When Miller met his appointed guide, he was inspired by her beauty to quote Lord Tennyson: “A daughter of the gods! Divinely tall and most divinely fair.”

At age 29, Ina Coolbrith was not only beautiful, she was also an established literary figure, a regular contributor to Overland Monthly, the first nationally recognized literary magazine in the western United States. Miller, by contrast, was a relative unknown—a former miner, pony express rider, newspaper editor, judge, and horse thief who had spent time both living with Indians and fighting them. Now, this rustic from the northern frontier aspired to literary greatness. To that end, he had recently sent a book of his poems, Joaquin et al, to Bret Harte, the editor of Overland Monthly, in the hopes of getting a review. He succeeded. Though Harte allowed that Miller had a “true poetic instinct,” he added that Miller was “not entirely easy in harness, but is given to pawing and curveting; and at such times his neck is generally clothed with thunder and the glory of his nostrils is terrible.”

The criticism didn’t deter Miller, who had already decided to make Europe his literary springboard. That was where he was headed when he stopped in San Francisco to “meet the poets.”

The name of one poet in particular—Lord George Gordon Byron—was on everyone’s lips at the time, after publication of Lady Byron Vindicated by the best-selling author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe. Nearly a half-century after the great poet’s death, Stowe had, in Coolbrith’s words, “dragged the name of Byron from the grave to befoul it with a new scandal.” Among other things, Stowe accused Byron of incest. In an Overland Monthly review, Bret Harte characterized Stowe’s book as being transparent in its “solemnly ridiculous mingling of great moral principles with narrow methods and small applications.” Coolbrith was just plain angry: “I don’t know of anything that was not my business that ever made me more indignant.”

Coolbrith and Miller burned with “Byronic fever,” a malady Stowe had once diagnosed in herself. Coolbrith had practically been weaned on Byron’s verse, reading the lines from a dog-eared book her family carried into California on the Overland Trail. As for Miller, there was no doubt that he strove to be a Byronic figure in his own right. Indeed, friends called him “a second Byron.” His wife, from whom he was separated, had accused him of trying to emulate Byron—not just as a poet but as a cruel husband, as well.

When Miller told Coolbrith that he was planning to visit Byron’s grave in England, it gave her an idea: Why not make a gesture to show Europe that some American writers still loved the author of Don Juan and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage? What if Miller carried a wreath of laurel from California to crown the poet’s grave?

It was a quixotic idea. After all, who were these upstart western poets to think they could defy the great Harriet Beecher Stowe? Didn’t they know that the eastern literary establishment viewed western poets as amateurs, as green as the leaves of a laurel tree? And although laurel wreaths are the symbol of victory in classical Greece, they were Laurus nobilis; unrelated to the California bay laurel, Umbellularia californica.

Coolbrith described the steep hills of Sausalito as a “beautiful wildwood,” but today those same hills are packed with houses. To get a sense of the place in 1870, I looked at old photographs found at the Sausalito Historical Society. In one taken by Edward Muybridge in 1875, a man sits on a pier with his back to the camera, looking across the glassy surface of Richardson Bay. Rising behind the wharf are sandy hills, innocent of homes and covered in scrubby chaparral. Other photos depict a deeply wooded ravine farther up in the hills called Wildwood Glen. To get there, I followed the librarian’s directions and drove into the hills, winding my way up into the residential area, occasionally stopping when a view presented itself.

I tried to imagine what Coolbrith and Miller would have seen: the bare, tawny hillsides of Belvedere; the old parade grounds on Angel Island; across the Gate, in San Francisco, rolling sand dunes and coastal prairie shrub, the city itself tucked into the harbor on the eastern side of the peninsula.

I turned onto Glen Drive and found a place to pull over. It was noon, but in spite of all the houses, there were still plenty of coast live oaks, tanoaks, and California bay laurels to provide shade. Black-headed juncos scratched the ground, and a scrub jay squawked from an upper branch. At ground level, the air was still, but the tops of the tall, spindly laurels swayed hard in the wind. I plucked a long, dark-green leaf, folded it in half and put it to my nose. A distinctive aroma of pepper, lemon, and oak lingered in the air. I pulled on a low-growing branch to test its flexibility and felt for myself how the new growth could easily be bent and woven into a crown.

As Coolbrith worked on Byron’s crown, she began to weave a poem. Meditating on the wind, she asked it “To pause and thrill with twofold life/Each spicy leaf I twine.” She willed the birds to sing softly and sweetly as she lamented that Byron’s tomb was unblessed by wife or child. She entrusted the leaves to carry the Western wind, sun, and light to England. The poem, “With a Wreath of Laurel,” was published in Overland Monthly in September 1870. It ends:

I weave, and strive to weave a tone,

A touch, that, somehow when it lies

Upon his sacred dust, alone,

Beneath the English skies,The sunshine of the arch it knew,

The calm that wrapt its native hill,

The love that wreathed its glossy hue,

May breathe around it still!

The day following their excursion to Sausalito, Miller went to Coolbrith’s house on Russian Hill and packed the wreath and her poem into his valise. Before he sailed, she asked him how he expected to climb to the poetic heights of Parnassus with a name like Cincinnatus Hiner. She suggested he change it to Joaquin, after Joaquin Murietta, the infamous bandit who figured so prominently in Miller’s book of poems. And so it was that Joaquin Miller sailed to Europe to become, in due time, the social darling of London, famous as the “poet of the Sierras” and even the “Byron of the Rockies.”

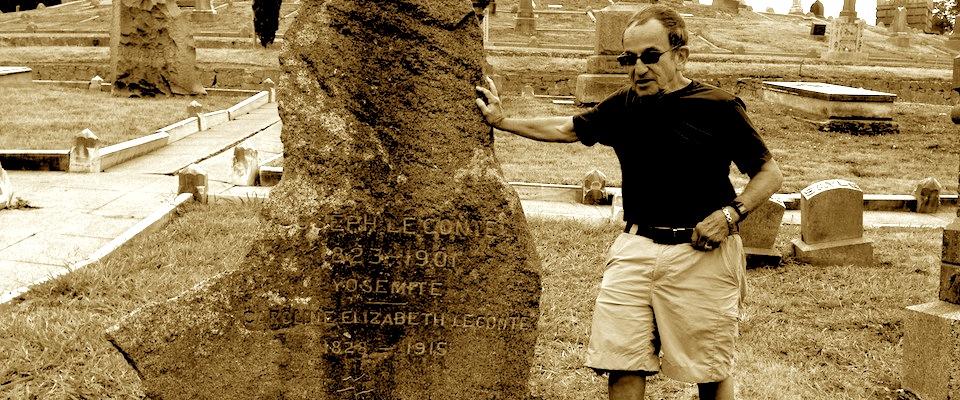

Miller was characteristically theatrical as he placed the wreath on Byron’s dilapidated grave in England, and he recorded in his journal that he paid the caretaker to nail it above the tomb to ensure that it remained there. When the parish priest objected to the crown, the Bishop of Norwich sent word to King George of Greece, where Byron was revered as a fallen hero. In response, the king sent a wreath of his own to the gravesite, along with a glass dome to protect both crowns.

In California, almost a full year after she and Miller had fulfilled their poetic mission, Ina Coolbrith was asked to write a commencement ode for the University of California graduating class. A clipping from Coolbrith’s scrapbook reports that on the day of the graduation, a party of alumni, wives, and invited guests would board the San Francisco ferry in the morning, cross the bay, and be met and escorted by “the battalion of University Cadets, and by all the military and fire companies of Oakland.” With the Berkeley campus not yet finished, the parade made its way to the Oakland campus.

That graduating class of five didn’t include women, but the University had begun admitting women the year before, and eight had enrolled. Overland Monthly reported that at the ceremony “the wives, sisters, and daughters of the alumni were not crowded back to the wall-seats, and quite out of the room…as on former occasions, but sat down as most welcome guests.”

Coolbrith was asked to deliver her ode, but she chose to have Reverend Horatio Stebbins read for her instead. The poem was titled simply “California,” and in it she gave the state a voice:

Are not the fruit and vine

Fair on my hills, and in my vales

the rose?

The palm-tree and the pine

Strike hands together under the

same skies

In every wind that blows.

Reviewing the occasion, Ambrose Bierce wrote of Coolbrith’s poem: “There is not another person west of the Rocky Mountains—now that Joaquin Miller is gone away…that could have done better.”

Miller did not go away for good, however. Eventually both poets wound up living in Oakland—Miller in the hills and Coolbrith in the flats, where she worked as Oakland’s first public librarian. Buried in the files of the California History Room of today’s Oakland Public Library is a note written in 1953 by an elderly doctor who remembered waiting patiently at the loan desk as a young boy, while “Miss C.” and Joaquin Miller “stood apart and apparently read poetry to each other.”