How can one communicate the essence of a city in 200 pages or fewer? Coming in at 157 pages exactly, Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas, published by UC Press in November 2010, eschews the prepackaged narrative of Love and Haight and unveils the boundless complexity of the City by the Bay. This nontraditional cartographical paperback, sized at a strikingly nonstandard 7 x 12 inches, illustrates San Francisco in 22 maps, ranging from “The World in a Cup: Coffee Economies and Ecologies” to “Death and Beauty: All of 2008’s Ninety-nine Murders and Some of 2009’s Monterey Cypresses.” Solnit, M.J. ’84, a critic and cultural historian who has written for The Nation, Mother Jones, Harper’s Monthly, and Orion magazine, doesn’t side-step the contradictions of a metropolis that houses both Bi-Rite and Bechtel. Instead, she leaps into the fray—and into the heart of what a city means to those who have known it well.

In a 2008 essay for Orion magazine, you say that “… art and politics ignite each other and need each other.” What political or social conditions prompted you to write Infinite City?

I think knowing where you are is very empowering and that there’s a lot that people in the Bay Area—and almost any place—really don’t know.

I suspect most San Franciscans don’t know that they’re showering in snow melt from Hetch-Hetchy. I think a lot of people in the Bay Area, and actually globally, think the Bay Area is a hotbed of progressive, left-wing, peace, anti-war what-have-you, when in fact we’re also the headquarters for Chevron, Bechtel. Since 1945, the nuclear weapons labs have been managed by the University of California. John Yoo, Condoleezza Rice, Michael Savage are all here—and we mapped all of those things. I think giving people a deeper grounding makes them more engaged citizens.

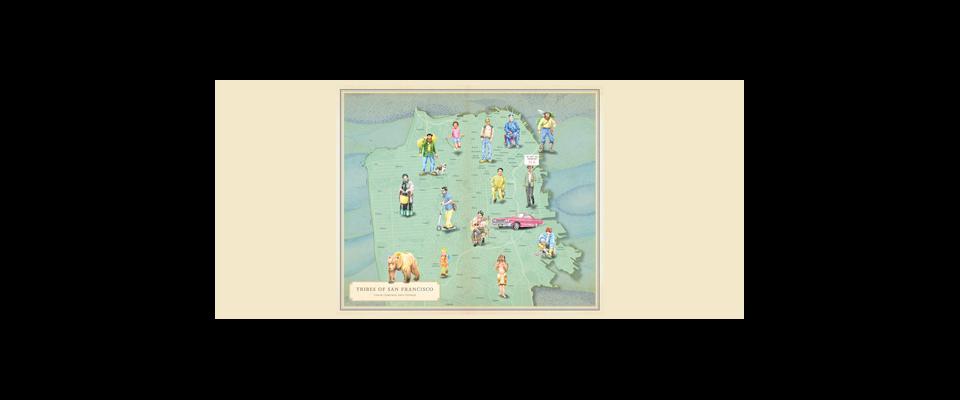

People don’t remember San Francisco used to be a great port town, they don’t know the battles that took place to create the massive amounts of open space we have, they don’t understand the ecology of day laborers and inner-city kids in the Mission…. My collaborators and I had the desire to give people a deeper, broader, more nuanced sense of what this place is.

With all the instantly accessible information, the impulse to turn disparate facts into coherent, narrative charts is now very present in the arts (the online journal Diagram and the “Schema” feature in The Believer, for example). Is Infinite City at all a reaction to the Internet age’s information overload?

You know, it is a reaction if you layer it in a certain way. The maps most people use to get from here to there are very conventional, and it feels like a lot of the sense of place, as well as what a map can be, has been leached out. For example, standard online maps show freeway exits and streets and places to spend money…. Land ownership, politics, the history, the soil type, the culture: all of those things are eliminated…. So it was a reaction to those aspects of technology, not the overload per se, because there’s certainly a lot of information loaded into the maps.

Maps are always arbitrary. To show freeways and restaurants is arbitrary. To show queer public spaces and butterfly species is no more arbitrary than that. So I also wanted to give people a sense of the arbitrariness, that maps are made out of value-driven decisions and priorities, and that’s something you should always be watching for. There were a lot of different agendas in this project, but a deeper sense of place and a reinvention of what maps can be in this era were two of them (reinvention because we tried to make maps beautiful again, too).

In the preface to Infinite City, you write that San Francisco is the “un-American place where America invents itself.” Is this a critique of those who call the city “un-American,” or is San Francisco actually un-American?

Well, I think there are two answers to that. One is that … during the Gold Rush, it became the place people came to reinvent themselves, to hide out from their pasts…. It was a place that was more tolerant of independent women, of Jews, of eccentrics, of a range of sexual behaviors. And it was a Catholic rather than a Protestant town, so it didn’t carry forward America’s Puritanical tradition. It was an immigrant town—it was always a town where a huge number of people had just gotten there from Chile or China or anyplace…. The people who insist they have the right to define America define it as white, Protestant, and straight, so we are definitely un-American in that sense.

But if you want to define America in another sense—the sense that I value—as being hybrid, innovative, open-ended, and unresolved, then San Francisco and the Bay Area are very, very American.