Half a century after the park’s founding, development looms.

It’s a quarter past three on a sunny spring Thursday in Berkeley. After weeks of rain, People’s Park is bursting with life: a sea of yellow, purple, and red flowers pours from the gardens on the west side of the 2.8-acre park, while the occasional gust of wind carries the scent of jasmine. People occupy nearly every available picnic table and bench, shedding jackets with gusto; a dozen more bodies sprawl out on the park’s main lawn. A couple of men play conga drums at the curb between the basketball court and the mural-covered bathroom. The moment is almost idyllic—until a third man emerges from said bathroom to deliver an update on the facility. “There’s poop everywhere!” he says, to no one particular.

Welcome to People’s Park: a study in flowers and filth, beauty and blight.

Let’s take a quick tour, shall we? Walk over to the corner of the park near Haste Street—to the north of the stage, where volunteers from the collective Food Not Bombs are setting up today’s free lunch of curried lentils, rice, and vegetables. Go past the bulletin board plastered with signs that read “SAVE PEOPLE’S PARK” and other activist messages, and you’ll find, all but lost in the greenery, the park’s most iconic signage: “Peoples Park, power to the people,” it reads. And below that, the park slogan: “Everybody gets a blister.”

On Dwight Way, we find 81-year-old Michael Delacour, one of the park’s original founders, standing in a tie-dyed shirt, natch, holding a plate of food, and observing the de facto marketplace in the southwest corner of the park, where a group of ragged young folk sell clothes, trinkets, weed. If you want to know about the park’s unspoken rules, below-the-surface racial tensions and turf lines, Delacour—very much the wise elder of the park—is the person to ask. But at the moment, he’s busy gearing up for a big anniversary. There’s a concert coming up featuring (who else?) Country Joe McDonald and the Garthwaites from Joy of Cooking. There are forums to attend, rallies to plan, campaigns to be waged. For Delacour and a patchwork group of old-timers and younger activists, the struggle for People’s Park continues.

As I write this, it’s been 50 years to the week since Delacour and a group of other idealistic anti-war activists, angry that the University had torn down houses on the land and left it to become a muddy parking lot, borrowed shovels and gardening equipment and built this park as a living testament to free speech and radical self-determination.

Things quickly came to a head. Just 25 days later, the University erected a fence around the park and tore up what had been planted, kicking off a riot that would come to be known as “Bloody Thursday.” Before the dust settled, police had killed one young man, James Rector, and blinded another; more than 100 other Berkeley residents were admitted to local hospitals with injuries.

That’s the quick version of how this space became a canvas upon which to project utopian visions and radical disappointments, a saga that, 50 years later, is still thoroughly entangled with the mythos of Berkeley itself. But in 2019, the story includes a few other pressing realities that may finally spell an end to this chapter of the park’s narrative—namely, a glaring lack of student housing. The University currently provides rooms for little more than 25 percent of its undergrads and fewer beds per student than any other school in the UC system. In May 2018, Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ, citing the housing crunch and concerns over crime and safety, announced plans to build housing on People’s Park as early as the summer of 2020.

The generation that participated in the park’s founding is dwindling, and younger Berkeleyans are more likely to associate the park with chronic homelessness than utopian yearnings.

This is no small development. As Sam Davis ’69, Berkeley professor emeritus of architecture, put it, “With every chancellor until now, [People’s Park] was like the third rail.” But unlike previous attempts by the University to build on the land (many Berkeleyans will recall 12 days of riots in 1991 over the construction of volleyball courts), these plans include a careful nod to the park’s origin story, as well as to the homeless people who have long been the park’s most regular denizens. Designs call for a student residence of up to a thousand beds that also includes 75 to 125 units of “permanent supportive housing” for the city’s unhoused population. In addition, the plans suggest that part of the park be maintained as “open and recreational space,” and call for a “physical memorial honoring the park’s history and legacy.”

By all accounts, the plan is enjoying an unprecedented level of support from city government: Where former Mayor Loni Hancock once compared building on People’s Park to constructing a dormitory at the site of Gettysburg, Berkeley’s current mayor, Jesse Arreguín ’07, has voiced enthusiastic approval.

Some say this can be explained by the severity of the aforementioned housing crisis. To others, it’s the natural result of time passing: The generation that participated in the park’s founding is dwindling, and younger Berkeleyans—especially incoming freshmen, who are cautioned away from the park at orientation—are more likely to associate the park with chronic homelessness than utopian yearnings.

For his part, historian and Berkeley grad William Rorabaugh believes the struggle over the park “will only come to an end when everybody who was alive at the time is dead. In the mind of some people, it’s always going to be a sacred space. … Unless, of course, you’re 25 years old and you’re looking for a place to live in Berkeley today.”

Many close to the situation say that day hasn’t yet come: As a slew of activist groups gear up for the anniversary, with teach-ins and rallies, there have been inklings that substantial protests are possible. Independently organized workshops and rallies over the past six months have drawn a mix of activists young and old, including Berkeley undergrads who say the University sends the wrong message to new students about the park, biasing them against it.

Already there have been signs of trouble. Early on the morning of December 28, arborists began work removing dozens of trees that the University had deemed dangerous. After protesters prevented the work from being completed, authorities tried again on January 15, this time stationing dozens of CHP and UC Police Department officers around the park for protection.

Tensions only escalated from there. A week later, at a march protesting both the tree clearing and the proposed development, a car drove through protesters and onto the sidewalk, severely injuring a 55-year-old homeless man.

No doubt, all this violent commotion over a mere parcel of land baffles outsiders—and understandably so. The long-simmering battle over People’s Park is a distinctly Berkeley conflict, the dimensions of which can probably only be understood by people who were there at its founding or who, today, feel invested in its survival as both a place and a symbol.

Meanwhile, for those who still gather here every day, victories are modest. An hour after the previous bathroom update, a different man emerges from the facility to announce the good news to three others sitting at a picnic table nearby. “Now there’s toilet paper!”

“It’s got the worst bathroom in the East Bay,” a 69-year-old man who goes by Stark Mike declares from his regular spot at a nearby picnic table, noting that he’s been coming to the park since 1972. “But it might be the last truly free place left in America.”

Ask any dozen people what they make of the University’s plans for People’s Park, and you’re likely to get two dozen different opinions. On the eve of the park’s 50th anniversary and ahead of possible development, what follows is an attempt to give voice to some of those opinions and to offer a snapshot of a deeply complicated and humble place.

For those of us who weren’t around in the 1960s, what do you think is important to know about the lead-up to the park’s creation?

William Rorabaugh, historian, author of Berkeley at War: People’s Park really was a culmination of so many of the hopes and fears that were going on in Berkeley at the time. By ’68, heroin was beginning to take over the Haight-Ashbury, it was getting dangerous there at night, so a lot of the hippies moved to Berkeley. That coincided with suburbanization and many middle-class families abandoning Berkeley. And there were all these older, cheap rental houses on the south side of campus. So you wind up with 10,000 people in their 20s who were not students at the University living between south campus and the Oakland city line. And that was the counterculture.

Tom Dalzell, author of The Battle for People’s Park, Berkeley 1969: 1969 didn’t come out of nowhere. It was after four years of really passionate protest against the war, and people getting burned out by that and wanting to do something positive. And in many ways it became just a microcosm of sixties values—this rare confluence of street people and hippies and politicos and anti-war people and students and neighbors and professors. It really was all kinds of people coming together to make something happen.

William Rorabaugh: UC owned this property and tore down all these houses because they were going to build dorms, but the federal funding that would finance the dorms came to an end, because [President Lyndon B.] Johnson was spending all the money in Vietnam instead. So the University left this vacant lot sitting there for two years, and it became a muddy parking lot, and people were angry that they replaced it with nothing. Then in the spring of 1969, a group of idealistic young people decided to make a park out of it, to plant flowers and shrubs, to make it a community gathering place.

Dan Siegel, J.D. ’70, lawyer and activist: I describe it as an effort of self-determination for the campus community, to improve the piece of property to make it accessible to students and members of the community, for regular park purposes.

The park existed for 25 days. What do you remember of that period?

Terry Garthwaite, musician: I remember the park was a beautiful, underused location, and what they made there was something lovely and heartfelt, and usable by everybody—not just the University. It was a joyous feeling. Like so many protests, there’s a togetherness that happens, and a joy in the working together, until whoever it is that’s in charge—the government or the cops or whoever makes the decisions—changes the energy, does whatever they think is right. Which it usually isn’t.

Dan Siegel: It was idyllic. It was a great spring, lots of people had become involved in the park, and it had become clean and green and safe. I remember being struck by how many parents took their small children there to enjoy the park. The other thing was there was a lot of tension about what was to occur there, but I knew from my personal experience that conversations between [the University and the community] were ongoing; it hadn’t gotten to the point of impasse.

Tell us about the events of May 15, 1969.

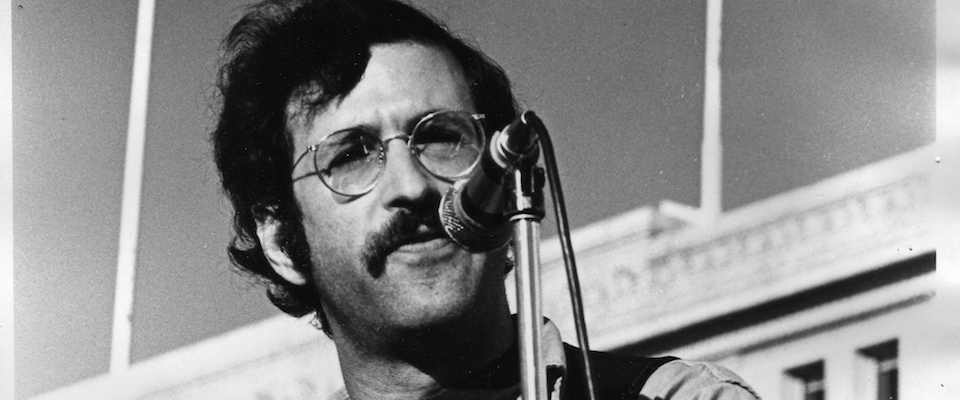

Dan Siegel: I lived on Bowditch Street at the time, about a block away, and I got up in the morning to pick up my newspaper. I looked to my left and I could see that the California Highway Patrol was there and that people were putting this fence up. The campus was very much in an uproar about what had occurred, and people felt extremely betrayed by the University’s actions. So the noon rally which had been scheduled for some other purpose—at that point there was a rally every day on Sproul Plaza—instead became about the park, and by noon, there were a couple thousand people there, a large crowd.

I went to the rally just intending to be present; I had just been elected student body president, so someone called out to me, “You should say a few words at the rally.” It was around 12:30 when I spoke, and I spoke for less than five minutes before I said, “Go down there and take the park,” and after that, the sound equipment was turned off.

There were a couple people waiting to speak who were ticked off at me for ending the rally. But ultimately, people started to drift down Telegraph Ave toward People’s Park. Now, the crowd that left Sproul Plaza was not a riotous crowd—you see children being pushed in strollers, you see people carrying balloons and eating ice cream cones. It wasn’t until there was this standoff with police at Haste and Telegraph that all hell broke loose. And the rest is pretty much history.

Tom Dalzell: In my research, I was struck by how all the press reports did such a good job of vilifying [protesters] as troublemakers. When you look at the stuff in the press about James Rector, it’s all about, “Oh, he had stolen items in the trunk of his car.” And you look at the impunity with which [California Governor Ronald] Reagan lied, saying the sheriffs only brought out shotguns when all else failed, or they didn’t use buckshot, only birdshot—shameless lies, all the way through.

What was your first experience or impression of the park as a student?

Jesse Arreguín ’07, mayor of Berkeley: I remember hearing during my orientation about Telegraph and the history of People’s Park, but also being cautioned about the park—how dark it is around there, and that you need to be aware of your safety. As a student I lived in Unit 2, which is a block away from the park, so I had to walk past the park every day to get back to my apartment, and I definitely felt unsafe. While the park is a great amenity for recreation, it wasn’t used all the time, it wasn’t a place to hang out—it was a place for people who were homeless to live. And every month we would hear about crime in the park…. It was clear to me [even then] that there was a disconnect between the vision of the park and what the park is now.

Marbrisa Flores ’20, student, homeless advocate: The freshman dorms are right next to the park, and one of the first things everyone tells incoming students is, “Don’t go to the park, don’t walk by at night.” I didn’t learn the history of the park until I started getting involved with the Suitcase Clinic. That’s also when I started going into the park, getting to know people there, and I found that it was the complete opposite of what students are told: That it’s just crime. I found an actually really lovely community there, and started hearing about what the park meant to people and also about the history, how it’s not just another park.

Why do you come to the park?

Sunshine: This is my family—I grew up in this park, from ages 12 to about 19. I first came here after I ran away from a foster home up in Washington state. I hopped a train with some friends and wound up in Oakland, and then someone took me here. I’d stay here and another spot in East Oakland, but if I ever had any issues, I came here. And then I left when I got pregnant with my first, went to Washington again, but now I’m back. People give you clothes, give you food. The park provides for you. And we all try to take care of it, we’re always picking up stuff at the Dollar Tree to try to clean the bathroom or make it nicer.

Eric Morales: I’ve been coming to the park for around five years—I grew up in Guatemala in the ’80s, during the revolution in Central America, and when I came here, I was doing some classes at City College in San Francisco and I learned about Berkeley [history] and the park and that it was about fighting for the same goals [as in Central America], and I made that connection. When you talk about the park’s legacy—we practice it every day. People plant flowers, people do the garbage, I do a lot of painting. We’re just here enjoying life and trying not to bother each other. Things happen because we’re human, but it’s a family. You can be yourself here.

Is it dangerous in the park?

Dan Mogulof, University spokesperson: I think we would be remiss if we didn’t make sure that students arriving here were made aware of the fact that the park has unfortunately been the locus for a pretty large number of bad deeds in recent years. And I think parents would be rightfully upset if we didn’t make an effort to inform them of that as well—just as we do about other areas that present unnecessary risk. It’s the same reason we have an escort service, provide rides at night to students who need them. It’s just part of the responsibility we have, and it’s not something we can or should put our head in the sand about.

Lisa Teague, People’s Park Committee: I think [the University] consistently demonizes it so the students are scared of it. This should be a natural place for people to come—it’s so close to campus, but it’s been painted as this scary, terrible, horrible place. Most of the crime in the park is some sort of small fight between the people who use the park regularly or a substance abuse problem.

Tom Dalzell: [The University] has so neglected the park—I think intentionally—to make it so unattractive that students who are unversed in its history will say, “Why would I fight for this?” But there’s no doubt to me that they’ve hyperbolized the problems there. The needles, the crime, violence. I walk the park from time to time, and I’ve never found anything but friendship there.

Dan Siegel: Obviously, it’s a long discussion of why we have a lot of people in this society who don’t have jobs, don’t have places to live, have untreated mental health or addiction problems that society doesn’t deal with, so they’re left on the street and they congregate where they can as best they can. I don’t think you can blame that on People’s Park. You have to say, “What is wrong with the richest society in the world that we have so many people who are not cared for?” I just don’t think it can serve as justification for paving over the park, any more than it could serve as a justification for paving over Oakland City Center.

What do you make of the University’s current plans for development, which include 100 to 125 beds of “supportive community housing,” green space, and a memorial?

Hugh Romney, aka Wavy Gravy: [Laughs.] That’s very sneaky of them. Devious. How could you object to that? But I wouldn’t hold your breath.

Marbrisa Flores: I think from the outside looking in, it seems like a great development—there’s this message of, “It’s not just student housing, we also care about this community.” But from what we know now, the people who get to live there will have to go through a screening process about need, and it might turn out to be mostly children, mothers, families—which is great, but that likely means the people who frequent the park right now will not benefit from that supportive housing.

Adam Ziegler, student, People’s Park activist: I disagree with the University’s plans to build on the park in general. I think it’s wrong to build on this deeply historical thing that emerged in the anti-war movement, from community activism. There’s nothing else really like it in the rest of the world: If you look at the modern Occupy movement, [the park is] an occupation that’s been going on for 50 years. People took a dirt lot and made it into a place for the community.

Mayor Arreguín: When you look at the disconnect between the original intention of the park and what the park is today, that’s why I’m so excited about the University’s plans. It’s not only re-envisioning the park as a place to provide for students but as a place to provide for the most vulnerable people in our community. Obviously, there’s a contingent that feels very strongly about keeping it a park, and I’ve been very clear to the chancellor that we do still have a need for open space—especially when we’re talking about bringing more people to the Southside of campus, which is already very dense.

Dan Mogulof: The University does not believe that the park in its current usage is in the best interest of the campus or its community; it’s not really in line with all that led to its creation, and there remains a significant question about the extent to which nostalgia should play a role, given the housing crisis faced by our students, as well as by members of the homeless community.

Sam Davis ’69, Berkeley professor emeritus of architecture, chancellor’s advisor on homelessness: I’ve been working on homeless issues for 30 years now, and I do believe we [the University] have abdicated our responsibility [when it comes to stewardship of the park]. … All we can do is do it correctly from here on out. We have a lot of support from different entities—the city is behind us, the Telegraph Merchants Association, the church across the street. In that neighborhood, a lot of people support a change, which feels different than in years past. As the chancellor has pointed out, the place is not what it was originally intended to be. That said, we have to take seriously the people who do use the park on a regular basis, many of whom are homeless, and we’re doing our best to handle it with dignity. I know some people will always be suspicious of the University.

Dan Siegel: I appreciate the housing problems that Berkeley faces, especially when they’re talking about expanding the campus to 45,000 people. Now, is that a good idea or a bad idea, and who will benefit and who will suffer as a result of that, is another discussion. But the University appears to have a lot of land available to it for building student housing, so I don’t think that’s a legitimate justification for the University’s plans, either. And I think it shows a lack of sensitivity to the People’s Park’s history and to what it means to the community, as well as to the need for a real park. If we’re going to have more students in Berkeley, fine, but to me, that increases rather than decreases the need for green space near the campus.

Talk about the memorial aspect.

Sam Davis: We’ll be putting out a call for [artist submissions], and I hope someone gets really clever and comes up with something like Maya Lin did for the Vietnam memorial—something that resonates with people, not just a photomontage. I personally would like to see it put up for a competition.

Dan Siegel: Maybe it’s personal, but I don’t want the University of California to decide how to memorialize People’s Park. The University is on the wrong side of that.

What should we expect to happen next?

Tom Dalzell: I think what’s going to happen is what the University wants to happen, everybody else be damned: “We do not care about the history, we do not care about the neighborhood, we don’t care about anything other than monetizing this piece of real estate, at a time when our budget is in trouble because of Memorial Stadium.” I don’t know if the resistance exists. I think it’s obvious that they waited until the sunset years of many of the activists involved the first time around.

Dan Siegel: I have taken part in some of the forums and discussions over the past few months, and I’ve been pleased to see participation by not only people from my generation but the current generation of students who have showed up and expressed interest. It’s really hard to imagine it would be the same as in the late ’60s, when you could count on a core group of at least a couple thousand activists to participate in anti-war and pro-civil rights activities. Clearly, that’s not where we are today, but you look back at what was taking place with the Occupy movement much more recently, and obviously, that generated a lot of interest [among young people].

Wavy Gravy: I think the people will rise up and block [development]. That’s what happens every time.

Stark Mike: It depends what they do and how mean they are about it. They tend to strike first, right? I don’t think we want a fight, but we’ll be there if we need to. Ever since they murdered Rector, they’ve kept it cool on violence [during protests]. But they haven’t said they’re sorry. We would like a public apology from the University for the murder and the blinding and the wounding of hundreds of people. They’ve never said they’re sorry. And that’s a crime. You put that in the paper.

Editor’s Note: Just as we were making final edits to this story, a homicide occurred in People’s Park. A little before three in the afternoon on Friday, April 26, a man entered the park with a handgun and fired multiple shots into the victim, who was sitting at one of the picnic tables in the garden area. The attacker fled by car, and the 43-year-old victim was rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead. A man suspected of killing two other men on the same day is in police custody.

This was not a common occurrence. According to Sgt. Nicolas Hernandez, the UC Police Department has crime records for the park going back to 2002. There have been no other homicides in People’s Park during that time.

Emma Silvers is a San Francisco journalist who grew up in Albany (the one next to Berkeley). Previously the music editor at KQED and SF Weekly, she currently writes for Pitchfork and the San Francisco Chronicle.

From the Summer 2019 issue of California.