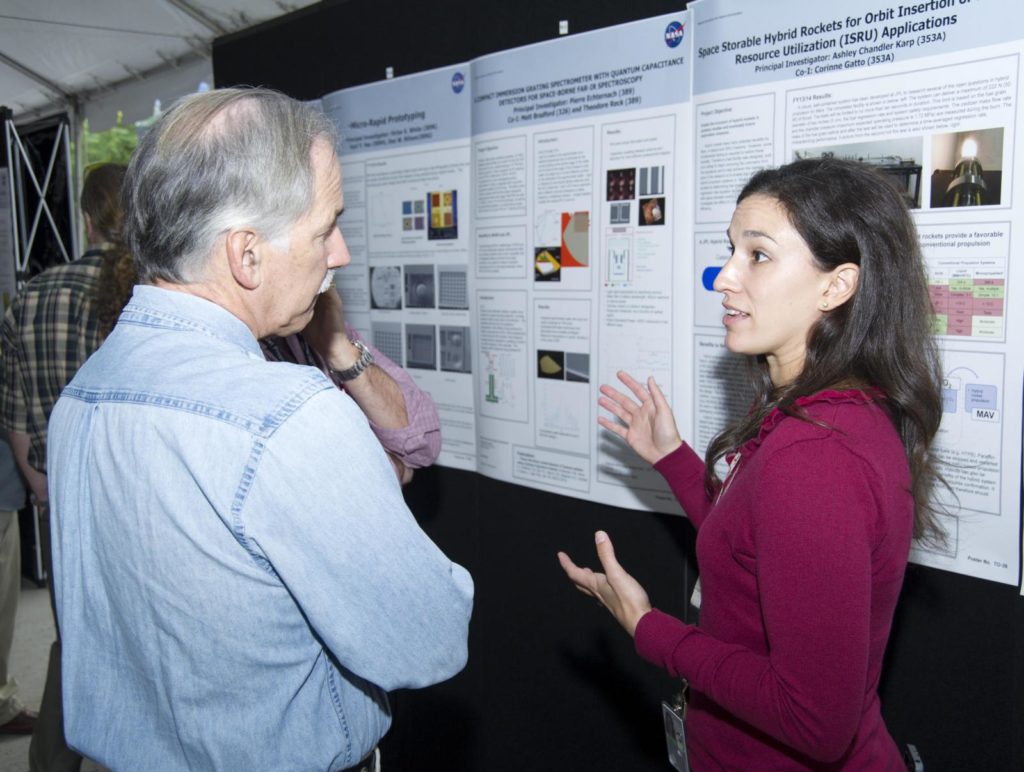

Ever hear that old cliché “This ain’t rocket science?” I wouldn’t use it around Ashley Chandler Karp because what she does is rocket science. A propulsion engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, she’s helping design the next generation of rockets, which will bring samples from Mars back to Earth for more extensive testing than can be done on the Martian surface.

As if that weren’t ambitious enough, they also have to figure out a way to transport the stuff here without getting any contamination from the Red Planet on the container.

“We have to have it completely encapsulated to make sure whatever we’re bringing back is completely sterile on the outside, not bringing back any Mars bugs,” she says. “We’re trying lots of different ideas to break the chain of contact with the Martian surface, including welding, brazing, and bagging. I’m working on paint that will burn off and sterilize the surface of the container as it burns. One problem is that we don’t know what temperature we need for Mars bugs. We don’t even know if they exist, much less how hot it has to be to kill them.”

Until recently, most rockets have been either liquid fuel or solid fuel, but Ashley is working on a new type: hybrids.

“Solid fuels have a lot of oomph, what we call ‘high thrust application,’” she explains. “Also, they’re very simple: Just hit ‘go’ and then you go until you’re out of fuel and oxidizer. The downside is that you can’t turn it off once you start the combustion process.” Liquid fuel, on the other hand, is much more controllable. You can throttle it up or down if necessary or even shut it down completely. But it’s very complicated. You have to get two liquids—the fuel and the oxidizer—through the plumbing system into the combustion chamber at the same time.

“Hybrids are a happy medium. You get the controllability and high performance of the liquid and the simplicity of the solid. And you only have to get one liquid—the oxidizer—through the plumbing.” (Ashley’s graduate school advisor once told her, “If rocket science doesn’t work out, you can always be a plumber.”)

So what material is she using for the solid fuel? Something exotic, no doubt?

“Nope. Simple paraffin. If you see a candle burning, it has a liquid layer at the top. If you were to pass an oxidizer over the surface of that liquid layer, the shear force between the two creates a wave rolling across the surface and also rips off droplets and entrains them into the flow. It creates the equivalent of a fuel–injection system, so you basically get a lot more fuel burning than you would otherwise. That’s why we like these wax-based fuels.”

“We need more women in science, for sure,” says Ashley Chandler Karp. “I’ll look around the room in meetings, and I’ll be the only woman in the room, or one of only two or three. It’s a bias that goes back to my childhood. When I was a little girl I had a tool belt, but the only color I could get was blue. I so wanted a pink tool belt!”

Ashley didn’t start out to be a rocket scientist. “When I was little, I wanted to be the first female president, but I got a little lost along the way somewhere. I found out about dinosaurs and wanted to be an archaeologist. Then I heard about King Tut’s tomb and wanted to be an Egyptologist. In the fourth grade, I started reading Nancy Drew books and wanted to be a detective.”

But in high school, her mother convinced her to be a lawyer, despite her growing love for math and science. (Her mom thought law would be a safer career than rocket science.) So she applied to Cal as a political science/astrophysics joint major. “But after a semester, I realized that with only a few more courses I could be a physics major, too, so I ended up as a triple major.”

One of her greatest influences was Berkeley Nobel laureate physicist Charles Townes, the inventor of the laser, who died last year.

“He was operating these telescopes down at Mount Wilson, so I would commute to these telescopes one week and spend the next week up in Berkeley writing papers. His work ethic was unbelievable. At 90, he was working just as hard as us, and I was in my 20s. He wouldn’t take any breaks; he wanted to make sure the telescope would not move off the moving star he was watching. He was so excited about the work he was doing, always humming and whistling, and I really loved that.”

And he gave her great advice for life. “I was unsure of what I wanted to do, and he said, ‘Any problem, once you get into it, is going to be interesting. The real challenge is to pick the people you’ll be working with.’”

After Cal she got her Ph.D. at that school down on the Peninsula. Her dissertation topic was “An investigation of liquefying hybrid rocket fuels with applications to solar system exploration.” There she met another invaluable mentor, Professor Brian

Cantwell, an enlightened man in a field too long dominated by sexism.

“We need more women in science, for sure,” she says. “I’ll look around the room in meetings, and I’ll be the only woman in the room, or one of only two or three. It’s a bias that goes back to my childhood. When I was a little girl I had a tool belt, but the only color I could get was blue. I so wanted a pink tool belt!

“But [Cantwell] would talk to you like a normal person; he never made you feel like you were ‘just a girl.’ And if anyone made a sexist remark, he would defend us. He’s at Stanford, but he’s still fantastic.”

Today, Ashley lives in Southern California with her husband, Jonathan, a firefighter. “It’s handy to have a firefighter around for rocket scientists,” she jokes. “It keeps me out of trouble.”

Footnote: Despite her considerable accomplishments, Ashley is very modest and is reluctant to toot her own horn. Here are a few things she never told me about herself: 1. She began working towards her pilot’s license in high school. 2. She does triathlons. 3. She hikes to places like Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the lower 48 states, for fun.

________________________________

In January 2016, the League of Women Voters of Berkeley, Albany, and Emeryville hired Adena Ishii to bring it into the 21st century.

It was a wise move.

In 2014, just after graduating from Cal with a bachelor’s in business administration and management, Adena won the group’s Spirit of the League award—other awardees include Save the Bay co-founder Sylvia McLaughlin and former Berkeley Mayor and State Senator Loni Hancock—for leading a program to help community college students transfer to four-year colleges and thrive after they get there.

Now her job was to figure out how to attract her own generation to the League, whose members were getting older every year, and to diversify the membership.

“My goal as a consultant was to render myself obsolete, and I’ve succeeded,” says Adena Ishii. “Although I will continue to be a member, my objective was always to have them set up for the next year without having to pay me.”

“My biggest challenge was that the League has a very set way of doing things,” she says. “So it’s difficult to make radical changes.”

For instance, all the membership records were still on 3×5 cards. But Adena is nothing if not tactful, so she kept the card system because that’s what a lot of people were comfortable with—but she also copied all the information to an online database. In addition, she created a spreadsheet to track potential members.

Another innovation was switching meetings and recruitment events from the daytime to the evening. “Up to now, most of our members have been retirees, and afternoons are convenient for them. But students and working parents are on a very different schedule, and if you want to attract and keep them, it has to be after work.”

Formerly, League recruiters handed out nuts-and-bolts information pamphlets to prospective members. Now they hand out party invitations to membership socials. Adena also lobbied heavily for free memberships for the first year, which is ongoing through the end of the year. And they’ve lowered the renewal fee to $20 for students.

“We get them in the door, we invite them to new member socials, and then they can start getting involved right away,” she says. “If they’re really engaged, they’ll want to keep being members.”

As a result of her efforts, the League has gone from one or two new members a month to one or two every day.

“It’s been a really amazing experience for me,” says

Adena. “I’ve learned a lot of things and met some incredible women. So smart, so on top of things. I’m very humbled by them and grateful for the work the League does.”

In her spare time, Adena also worked part time for political consultant Larry Tramutola (a frequent guest speaker at Cal’s Institute of Governmental Studies) and helped former Piedmont Mayor Margaret Fujioka run her successful campaign for Superior Court judge.

“She was terrific!” says the incoming judge. “She organized events and fundraising and helped me with my campaign database and social-media outreach to voters, as well as accompanying me to a lot of events. It’s wonderful to see such a strong generation of future leaders like Adena.”

And what does 2017 hold in store for the League? Great things, no doubt, but Adena will be watching from the sidelines.

“My goal as a consultant was to render myself obsolete, and I’ve succeeded,” she says. “Although I will continue to be a member, my objective was always to have them set up for the next year without having to pay me.”

So what’s next for her?

“I don’t know. I’ve never applied for a job. I’ve always known people and got recruited. I met Larry at a League event, and he recruited me. I’m just waiting for the next exciting project.”