Romeo and Juliet, as Prokofiev intended.

Berkeley audiences have come to expect surprises from Mark Morris, the endlessly inventive American choreographer who set Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker in a boozy 1960s cocktail party (The Hard Nut) and transformed a musty British “semi-opera” (Purcell’s King Arthur) into an exuberant contemporary delight. With his latest work, though, Morris delivers something wholly unexpected—a Romeo and Juliet with a happy ending.

Romeo and Juliet, on Motifs of Shakespeare is a new twist on an old tragedy. Yet the concept of a happy ending for it didn’t originate with Morris. It was the brainchild of Russian composer Sergey Prokofiev, whose 1935 score for Romeo and Juliet originally featured an outcome radically different from the one audiences saw at the ballet’s 1940 premiere. Morris’s new choreography honors Prokofiev’s first take on the score—with the title and ending the composer intended but never lived to see performed. Cal Performances gives the work its West Coast premiere at Zellerbach Hall, in performances September 25–28 featuring the Mark Morris Dance Group and the Berkeley Symphony under the direction of conductor Stefan Asbury.

It’s hard to believe that one of the most popular ballets of the 20th century was never performed to the composer’s specifications. Yet, because of an odd convergence of Soviet art and politics, that’s exactly what happened to Romeo and Juliet. Prokofiev and his collaborator, dramatist Sergei Radlov, saw Shakespeare’s tragedy as a struggle for love between young progressives battling a feudal system. They devised an alternate ending to Shakespeare’s—one in which Juliet awakens just as Romeo concludes that she has died.

Prokofiev’s ending didn’t sit well with Stalin’s regime, and the composer was forced to rewrite the ending. He replaced the fourth act with an epilogue, and inserted solo dances for the ball and balcony scenes. An Act III divertissement was jettisoned, and orchestrations were thickened. When the revised work received its premiere at the Kirov Ballet in 1940, Prokofiev scarcely recognized it.

The happy ending went into the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art in Moscow, where it lay dormant until it was discovered in 2003 by Princeton University musicologist Simon Morrison. Plans were made to revive it, and conductor Leon Botstein asked Morris to supply choreography. Romeo and Juliet, on Motifs of Shakespeare made its world premiere on July 4 at Bard College, danced by the Morris corps with Botstein conducting the American Symphony Orchestra.

Morris, who was in Berkeley earlier this year when Cal Performances announced the premiere, said this version includes 20 minutes of never-heard music and six dance numbers never performed. It is, he said, vastly superior to the “confusing and inflated” rewrite imposed on the composer. “This is the original point of view of Prokofiev,” he said.

Asked to describe the happy ending, Morris declined to elaborate. “They don’t actually, fully die in the end,” was all he would say.

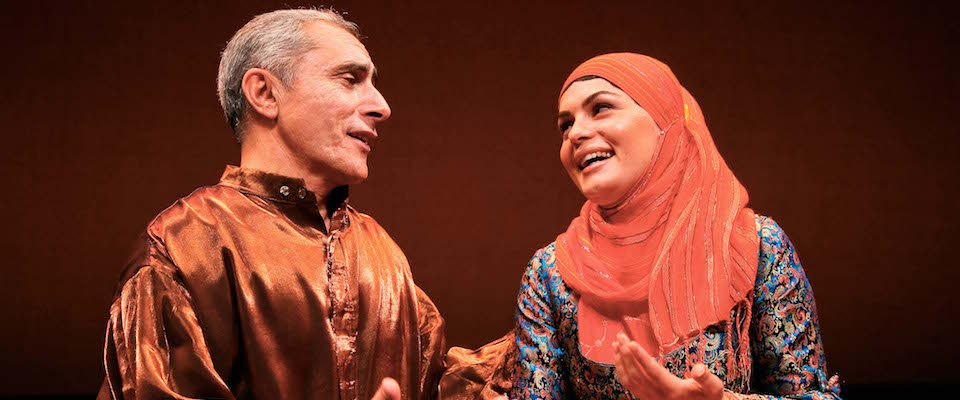

Maile Okamura, one of two dancers cast as Juliet (she’ll alternate in the role with Rita Donahue), described the ending as “abstract,” noting that Prokofiev was an avowed Christian Scientist. “It’s more of a spiritual ending,” said Okamura. “It sort of forces the audience to come to their own conclusions.”

Okamura, who joined the Mark Morris Dance Group in 2001, also called the ending satisfying. “In the original story, Juliet ends up getting the short end of the stick,” she said. “What she has planned so cunningly doesn’t really work out. In this version, it does.”

Morris’s choreography represents a departure from traditional Romeos. “I wanted it to be pre-classic, before ballet was invented,” said Morris. Okamura said that Morris worked with the cast to develop a specific movement vocabulary for the work—one that suggests the heat and grit of Shakespeare’s Verona. “He’d say things like, ‘These people don’t take baths’ and, ‘They don’t have teeth’,” she recalled.

One thing’s certain: Romeo and Juliet, on Motifs of Shakespeare gives audiences the opportunity to hear one of the 20th century’s premier dance scores, seen through the eyes of a brilliant contemporary choreographer. “The human element in Mark’s work is so strong, and the music is wonderful,” said Okamura. “This piece is different, because Mark doesn’t usually choreograph to music that was meant for dancing. This music was very much meant for dancing. The drama in the music propels you to that place instantly.”